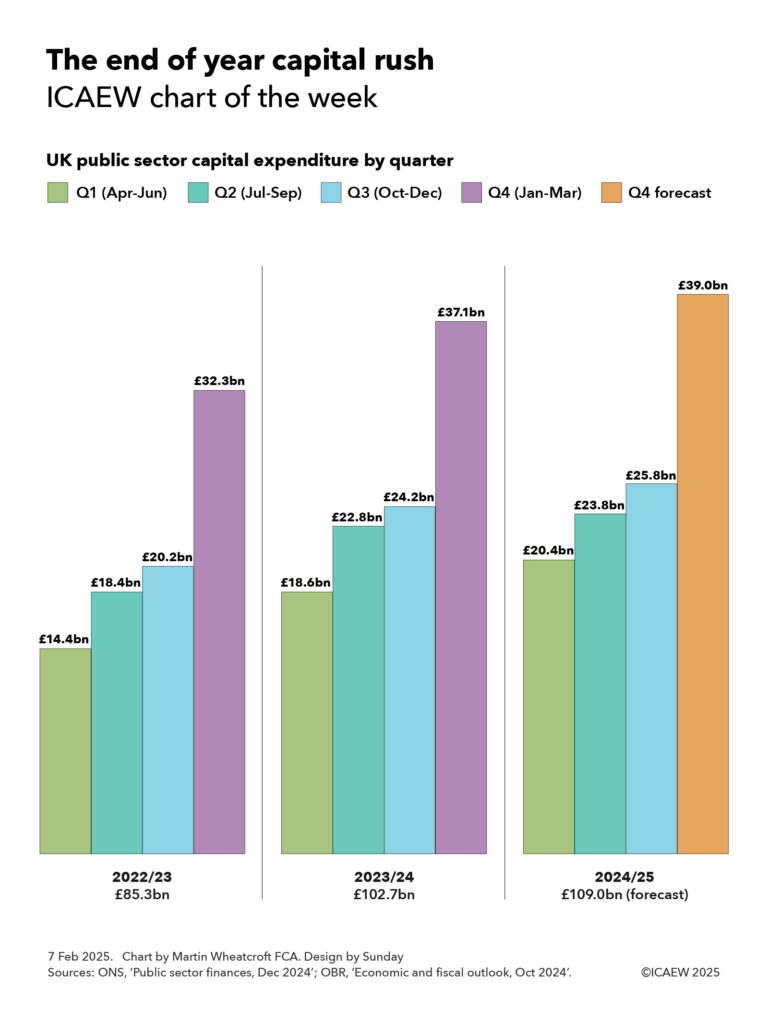

Our chart looks ahead to next week’s Spring Statement by looking back at the fiscal forecast prepared by the OBR last October.

There has been some confusion on both the title of next week’s Spring Forecast and whether it will or will not constitute a formal ‘fiscal event’.

Traditionally, each Chancellor of the Exchequer stands up in Parliament twice a year to announce policy decisions on tax, spending and borrowing, and to set out the latest economic and fiscal forecasts, which since 2010 have been prepared by the independent Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR). One of these fiscal events is a ‘Budget’, which involves requesting parliamentary approval of the annual budget for the upcoming financial year, while the alternate has historically been described as a ‘Statement’.

Chancellor Rachel Reeves set out an ambition on taking office for there to be only one fiscal event a year – an Autumn Budget – mostly in the hope of creating a more stable tax system by reducing the frequency of tax changes, but also to provide a more stable budgeting framework for the public sector. However, she is still legally required to present fiscal forecasts to Parliament twice a year, and so HM Treasury’s decision to relabel the second event as a Spring Forecast was originally intended to emphasise that there wouldn’t be any major tax or spending changes between Budgets.

Unfortunately for the Chancellor, weak economic data – and what that implies for the profile of public spending of tax receipts and public spending over the next five years – mean that she has been unable to achieve her hope of a policy-decision-free Spring Forecast on this, her first attempt.

Instead, the government has brought forward from later in the year its anticipated reform of disability benefits to ensure the associated cost savings are reflected in the new OBR forecast, while there are also rumours that she may, for the same reason, revise down the total amount of public spending allocated to this summer’s three-year Spending Review.

The tight fiscal situation is illustrated by our chart this week, which sets out how the current budget balance was expected to turn from deficits of £61bn, £55bn, £26bn and £5bn between 2023/24 and 2026/27 to surpluses of £11bn, £9bn and £10bn between 2027/28 and 2029/30.

Our chart also shows how public sector net investment of £70bn, £72bn, £80bn, £83bn, £83bn, £81bn and £81bn between 2023/24 and 2029/30 added to the current budget balance was expected to result in fiscal deficits of £131bn, £127bn, £106bn, £88bn, £72bn, £72bn and £71bn between 2023/24 and 2029/30 respectively.

The Chancellor’s primary fiscal rule is to achieve a current budget surplus by 2029/30, but the £10bn headroom against this target represents just 0.9% of projected receipts of £1,440bn and 0.7% of projected total managed expenditure of £1,510bn in 2029/30.

A deteriorating economic outlook is believed to have seen this headroom evaporate in the working projections presented by the OBR to the Chancellor as part of the Spring Forecast process – at least before taking account of any offsetting decisions by the Chancellor.

Similarly, the Chancellor may also need to take action to ensure that her secondary fiscal rule – for the debt-to-GDP ratio to fall between March 2029 and March 2030 – is met. This test (not shown in the chart) also had a relatively low headroom of £16bn in the Autumn Budget forecast and further changes to government plans may also be required to stay within it.

Many of the references in the media and elsewhere to the Spring Statement next week are likely to be from people who didn’t see the announcement from HM Treasury about the name change. We did get the memo, but on reflection we think sticking with the former title is going to be more appropriate on this occasion.