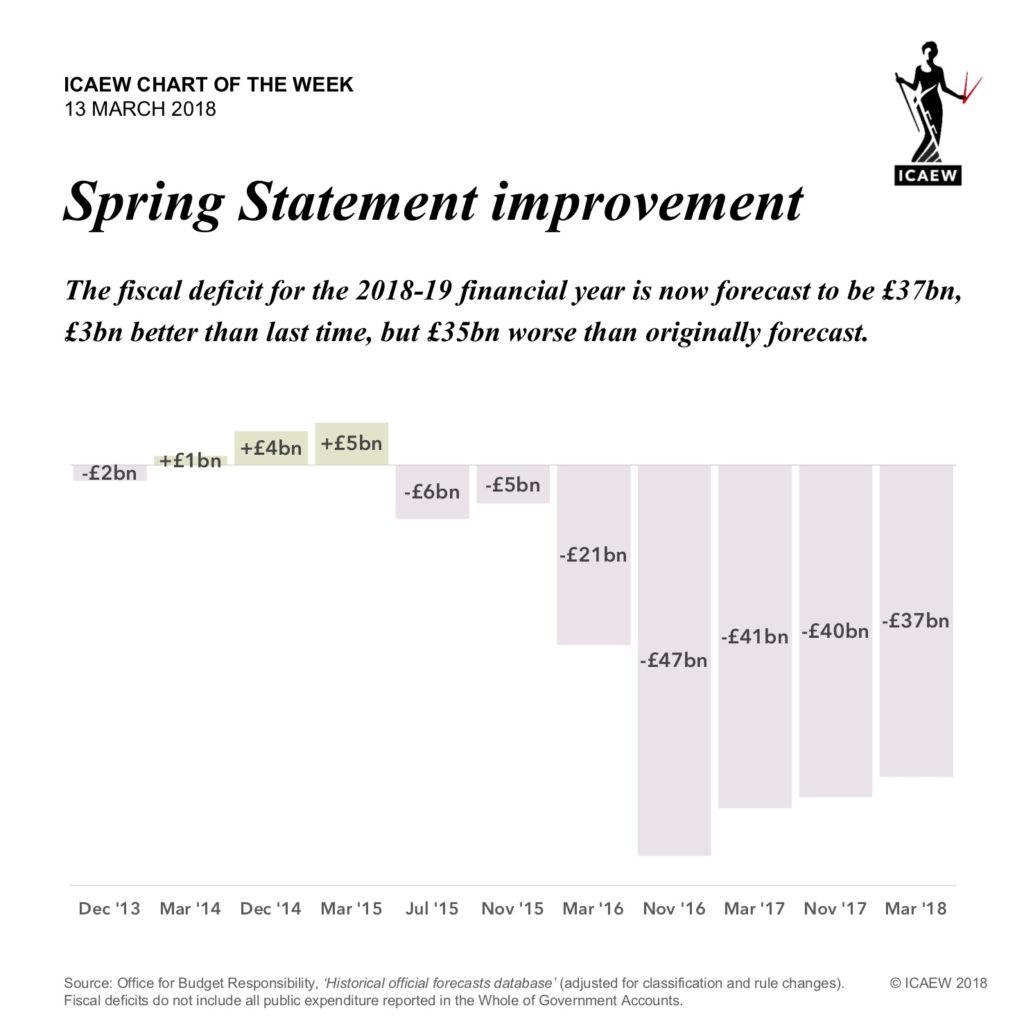

Our chart this week illustrates why some prudence in forecasting makes sense, given how the official forecasts for 2018-19 have changed significantly over a fairly short period of time.

The current forecast of £37bn may be £3bn better than the previous forecast and £10bn better than the shock Autumn Statement of 2016, but it is still £35bn below the original forecast made in December 2013 and is £42bn worse than the forecast of a surplus of £5bn made only three years ago.

The good news around the Chancellor’s Spring Statement was that he pretty much kept his promise of not announcing any fiscal policy changes. The numbers in the short-term are also slightly better, with a £5bn and £3bn improvements in the fiscal deficit expected for 2017-18 and 2018-19 respectively.

The bad news is that the medium-term economic forecasts remain extremely pessimistic and austerity continues.

This caution shown by the Chancellor and the OBR is driven by concern over the continued economic weakness, Brexit uncertainties and the inherent risks attached to making forecasts.

After all, Philip Hammond is not the first Chancellor to announce that public debt (as a percentage of GDP) has peaked and will start falling from now on…