Cost overruns have been a recurring feature of the modern Olympic movement, but the pandemic has blown the doors off the budget for the Tokyo games.

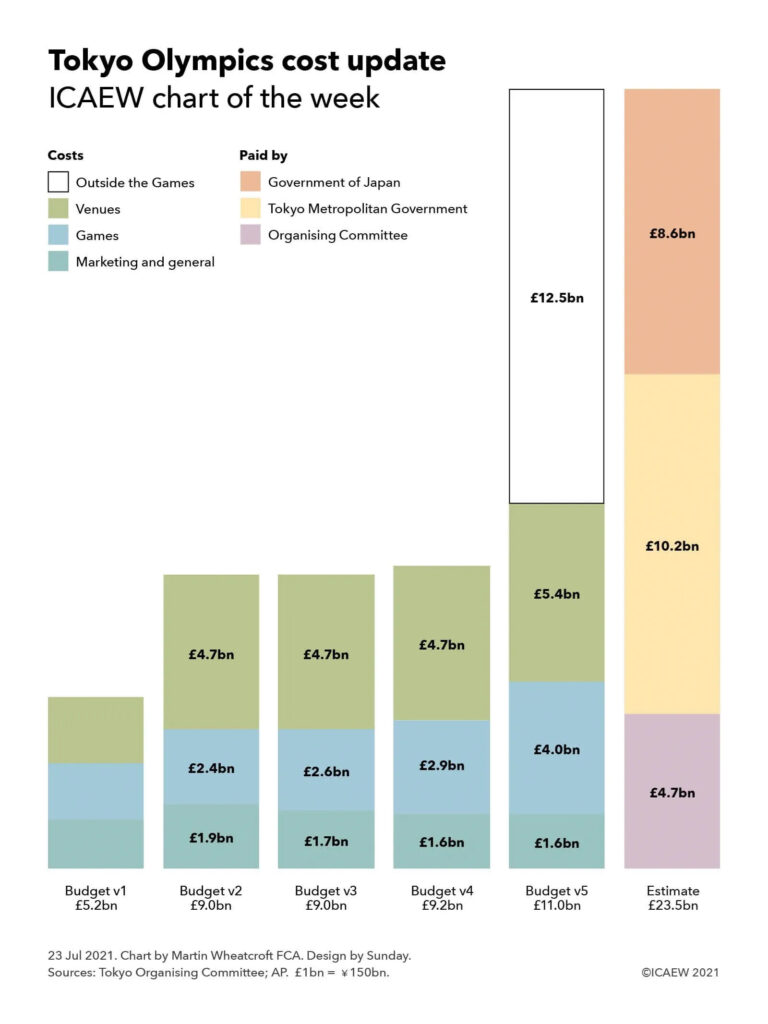

Hosting an Olympics is a costly affair, with headlines about budget overruns a regular occurrence in recent decades. The Tokyo Olympics is no exception, with the latest official budget for the rescheduled 2020 Olympic Games rising to ¥1.7tn ($15.4bn or £11.0bn) compared with an original budget of $7.5bn or £5.2bn.

Of course, nobody expected the original budget from Tokyo’s bid in 2013 to be the final result, but annual budgets since 2017 have shown a gradual rise in both the cost of running the Olympic Games and the cost of the venues. This would be unsurprising to those that remember the 2012 London Olympics, where the costs significantly exceeded the estimated overheads set out in the original bid.

The version two budget established in December 2017 of £9.0bn, comprising £4.7bn for venues, £2.4bn for running the Games and £1.9bn for marketing, communications and general expenditures was substantially maintained in version three with offsetting increases and decreases in different parts of the budget. Additional income allowed the organisers to add in a contingency to increase the budget to £9.2bn by 2019, with the budget for venues still £4.7bn, running the Games up to £2.9bn (including the contingency) and marketing and general expenditures down slightly to £1.6bn.

The pandemic drove a big jump in the version five of the budget, put together six months after the 2020 Games were supposed to have taken place. The budget for venues (permanent, temporary and energy costs) went up to £5.4bn, up from £4.7bn in previous budgets, while the version five budget for running the Games (transport, security, technology and operations) of £4.0bn is a third more than the 2019 estimate of £2.9bn and more than 60% higher than the 2017 estimate of £2.4bn, with marketing and general expenditures still at £1.6bn.

Not shown in the chart is the expected revenue that was anticipated to fund the Tokyo Organising Committee’s share of costs of £4.7bn, comprising £0.6bn from the International Olympic Committee (the IOC, which owns the global broadcasting rights), £2.8bn from sponsorship and licencing, £0.6bn from ticket sales and £0.7bn in other revenues. With tickets being refunded to spectators who can no longer attend, this leaves a hole in the Organising Committee’s finances that will need to be funded either by the IOC or by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government.

The chart also illustrates how the official budget for the Olympics is not the full story, with the Tokyo Metropolitan Government and the Japanese Government incurring a further £12.5bn or so in costs outside the Games, in addition to their already substantial contributions to the cost of venue construction. There are some disputes about these numbers as their spending include ‘legacy’ investments in public infrastructure that could be argued should not be counted, in addition to costs with a direct causal linkage, such as policing and security costs away from Olympic venues. The £12.5bn amount is based on AP reporting of a Japan Board of Audit report from 2019, but recent reports in the Japanese press have suggested the costs to the metropolitan and national governments of hosting the Olympics could end up being even larger.

While the pandemic was not foreseeable back in 2013 when Tokyo was awarded the 2020 Olympics, the budgetary tale highlights the importance of building in headroom for changes as well as considering contingencies when setting budgets. For example, there was insurance cover to deal with the risk of an event like the pandemic leading to a cancellation of the Games, but the insured amounts were insufficient to cover the full losses of a complete cancellation. This is no doubt one (but not the only) reason why the organisers are going ahead despite everything that has happened.

Fortunately for those of us who like watching sport on our screens, the Olympic Games and the Paralympic Games are going ahead after all and it is the performance of the athletes that will be our main focus for the next few weeks. We wish them the best of luck!