My chart this week is about domestic energy prices and the Ofgem energy price cap rises expected in April and October 2022.

The collapse of all but the largest energy suppliers over the past six months or so has pretty much ended a competitive market for domestic energy in the UK. Most consumers are now on tariffs that are at or close to the energy price cap set by the Office for Gas and Electricity Markets (Ofgem).

Originally designed as a safeguard for individuals on standard variable tariffs who couldn’t, didn’t or never got around to entering into competitive fixed-price contracts, the energy price cap is now expected to apply to most households as consumers either roll off existing fixed-price deals or – in many cases – transfer to one of the ‘Big Six’ energy suppliers following the collapse of one of the 40 or so energy firms that have gone bust over the past year.

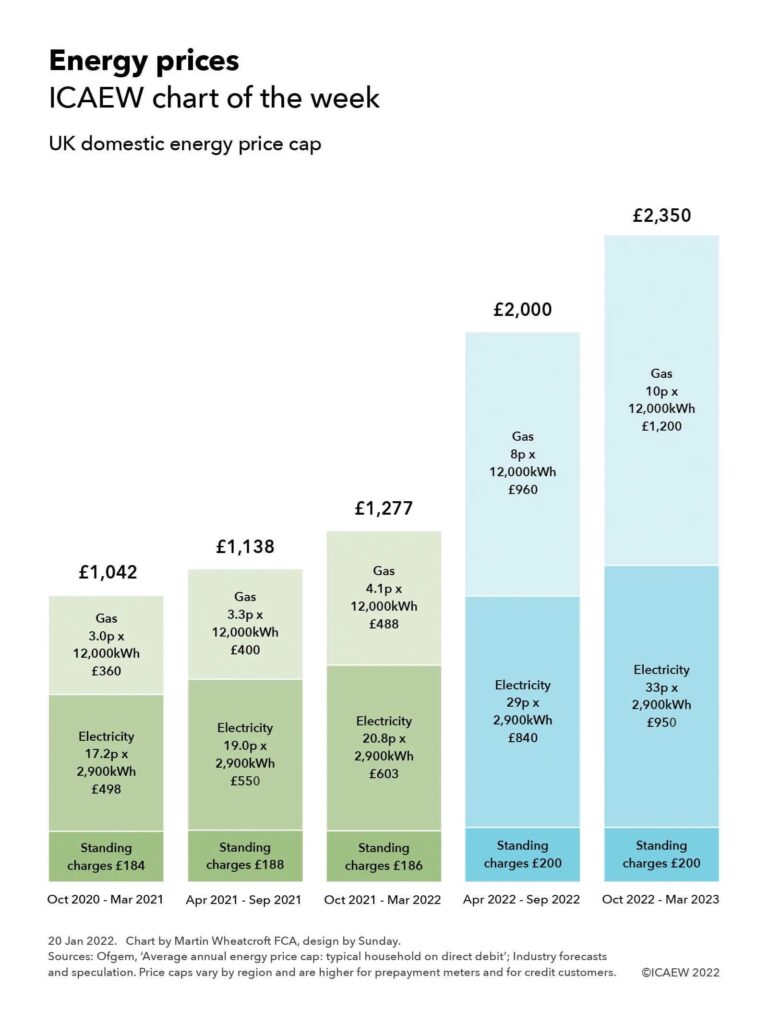

As a consequence, many consumers will have seen their energy bills increase by much more than that implied by our chart of the week, which shows how the energy price cap has increased from an average dual-fuel bill for direct debit customers of £1,042 a year (about £87 per month) between October 2020 and March 2021 to £1,138 (£95 per month) between April 2021 and September 2021, to the current cap of £1,277 (£106 per month) for the period from last October through to March this year.

These amounts assume ‘typical’ usage for a dual-fuel household paying by direct debit of 2,900kWh of electricity and 12,000kWh (410 therms or 41 million British thermal units) of gas, with consumers using prepayment meters or on credit paying higher prices – currently an average of £1,309 (£109 a month) and £1,370 (£114 a month) respectively. Those who use more or less will pay higher or lower amounts accordingly, while the price cap varies by region.

As the chart illustrates, the direct debit price cap during the six months ended 31 March 2020 of £1,042 per year comprised £184 for the standing charge, £498 for 2,900kWh of electricity at 17.2p per kWh and £360 for 12,000kWh of gas at 3p per kWh. This increased to £1,138 per year in the six months to 30 September 2021, comprising £188 for the standing charge, £550 for 2,900kWh of electricity at 19p per kWh and £400 for 12,000kWh of gas at 3.3p per kWh. The current price cap of £1,277 per year, which lasts until 31 March 2022, comprises £186 for the standing charge, £603 for 2,900kWh of electricity at 20.8p per kWh and £488 for 12,000kWh of gas at 4.1p per kWh.

The current price cap is based on annual wholesale energy costs of £528, network costs of £268, operating costs of £204, social and environmental contributions of £159, other costs of £34 and a profit margin of £23 before adding on £61 of VAT at a rate of 5%. These are equivalent to £44, £22, £17, £13, £3, £2 and £5 in an average bill of £106 per month, although in practice energy usage varies across the course of a year.

Recent industry forecasts and speculation from EnAppSys, Investec and Cornwall Insight, among others, suggest that the price cap is likely to increase by more than 50% to somewhere in the region of £2,000 a year (£167 per month) for the six-month period from 1 April and potentially to around £2,350 a year (£196 per month) for the six months from 1 October 2022. Publicly available forecasts do not provide a breakdown on what that means for per kWh prices and so the chart provides illustrative calculations based on gas prices doubling to around 8p per kWh in April and rising to 10p in October and electricity prices increasing by in the order of 40% to 29p in April and then further to 33p per kWh in October. Actual prices will depend on how Ofgem allocates costs between the fixed and variable parts of the bill, as well as how wholesale prices move before they are included in the final calculation. The cost of energy for prepayment meter and credit customers will be even higher.

The scale of these increases is likely to have a significant impact on poorer and middle-income households, with commentators suggesting that the government is likely to want to intervene in some way to cushion the blow. Some have argued for cutting VAT from 5% to zero, although the Institute for Fiscal Studies, the Resolution Foundation and HM Treasury have all noted that doing so would pass much of the benefit on to higher income households rather than helping those most affected. Others have argued for spreading higher wholesale prices over longer periods to reduce the hit to family budgets, while there are also calls for the taxpayer to provide temporary subsidies in order to keep bills down, potentially transferring some of the risk of higher wholesale costs on to the taxpayer.

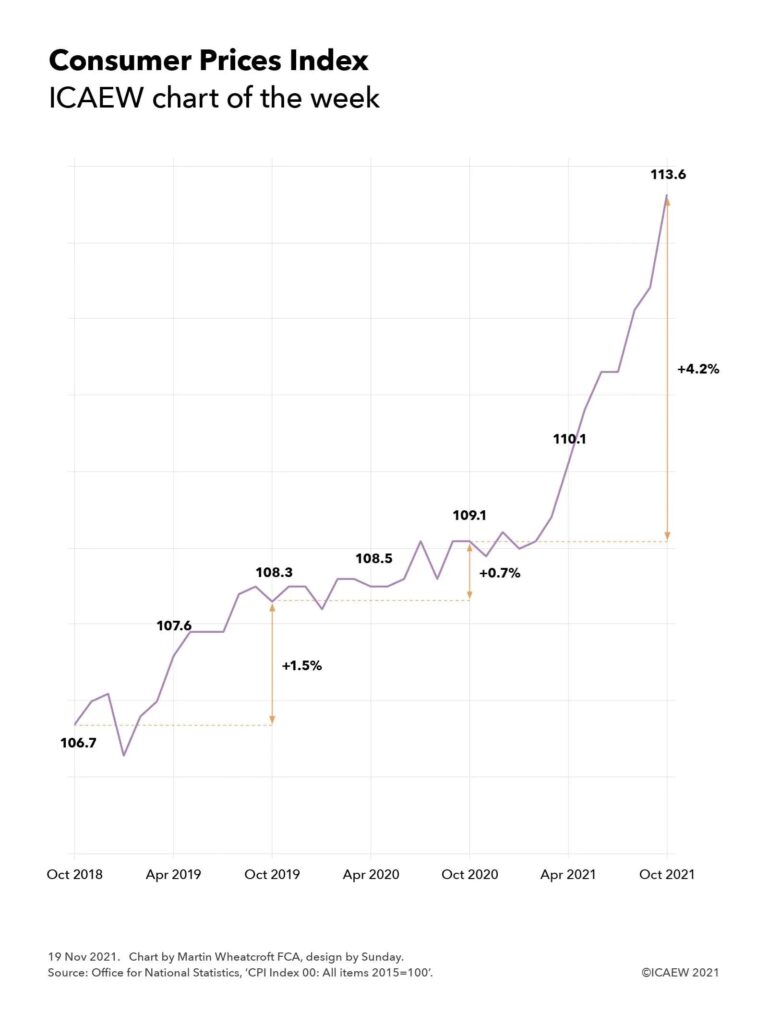

Policymakers are unlikely to do nothing as – even if there was additional support provided to the very poorest through the welfare system – the anticipated prices are large enough to disturb household budgets for many middle-income families as well. This could have serious implications for the economy and for public finances, with a substantial proportion of households likely to cut back on spending in other areas just as the government is hoping for a post-pandemic bounce to drive economic growth. The government will also be acutely aware that energy prices are a key component of inflation indices, with the consumer prices index 5.4% higher in December than a year earlier, according to the Office for National Statistics, and expected to rise even further once the new price cap comes into force in April.

There may be trouble ahead.