Our chart zooms across the Atlantic this week to take a look at Canada’s federal budget for 2024/25.

Canada’s budget 2024 sets out the financial plans of the government of Canada for the year from 1 April 2024 to 31 March 2025 (2024/25).

Like UK budgets, Canada’s budget 2024 is accompanied by financial projections for the four subsequent years to 2028/29. However, unlike the UK, Canada’s fiscal budget is prepared on an accruals basis, with a balance sheet including both financial and non-financial assets and liabilities, and a budgetary surplus or deficit that is equivalent to the accounting profit or loss in a private sector set of financial statements.

Canada’s approach contrasts with the statistics-based system of national accounts that most other countries use for setting fiscal targets, including the UK. This is despite the UK adopting International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) in its consolidated (Whole of Government Accounts), departmental and other public body financial statements, and an accruals-based resource accounting system derived from IFRS for internal budgeting and performance management.

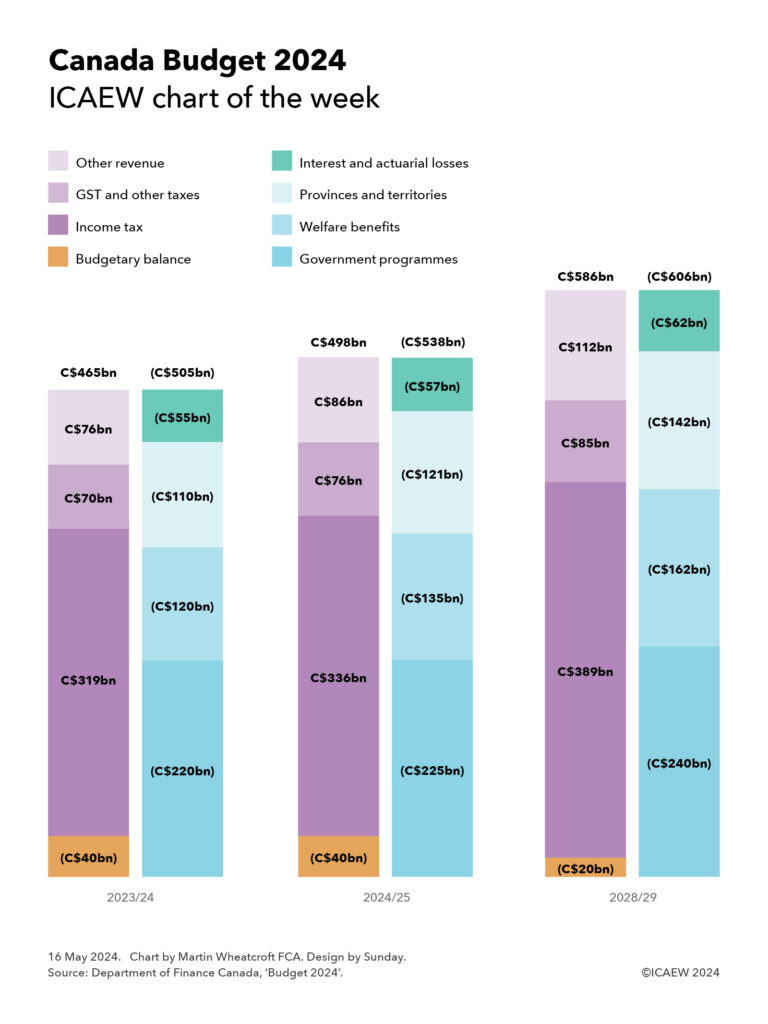

Our chart this week shows how Canada’s federal budgetary balance is expected to be in deficit by C$40bn in both 2023/24 and 2024/25, before reducing over the rest of the forecast period to reach C$20bn in 2028/29, equivalent to 1.4%, 1.3% and 0.6% of GDP in 2023/24, 2024/25 and 2028/29 respectively. Or £24bn, £24bn and £12bn if converted at the 1 April 2024 exchange rate of C$1.70 to £1.00.

Budget 2024 assumes an average increase in nominal GDP of 4.0% a year between 2024 and 2028, reflecting a combination of economic growth of 1.8% on average and projected GDP inflation of 2.1%. Economic growth is expected to reflect a 0.9% annual increase in labour supply (1.6% from growth in the working-age population less 0.6% from lower labour force participation, 0.1% from higher unemployment, and 0.1% from fewer hours worked) and 0.9% from improved productivity.

Total revenue is forecast to grow by 7.1% from C$465bn (£274bn) in 2023/24 to C$498bn (£293bn) in 2024/25 before rising by an average of 4.2% a year to C$586bn (£345bn) in 2028/29. This is equivalent to 16.1%, 16.6% and 16.7% of GDP in 2023/24, 2024/25 and 2028/29 respectively.

Around two-thirds of revenue comes from federal income tax, amounting to a budgeted C$225bn in 2024/25. A further 15% comes from other taxes, with the C$76bn in 2024/25 comprising C$54bn from goods and services tax (GST, the Canadian version of VAT), C$6bn from customs import duties, C$13bn from excise taxes and other duties, and C$2bn from other federal taxes.

Other revenue is budgeted to amount to C$86bn in 2024/25 or 17% of total revenue, comprising C$30bn in employment insurance premiums, C$13bn from pollution pricing, C$9bn in revenues from Crown enterprises (net of Bank of Canada losses), C$3bn in foreign exchange revenues (principally returns on international reserves), and C$31bn in other income (including interest on tax receivables).

Total expenditure including net actuarial losses is expected to increase by 6.5% from C$505bn in 2023/24 to C$538bn (£316bn) in 2024/25 and then by an average of 3.0% a year to C$606bn (£356bn) in 2028/29. This is equivalent to 17.5%, 17.9% and 17.2% of GDP in 2023/24, 2024/25 and 2028/29 respectively.

Expenditure can be categorised between government programmes, welfare benefits, transfers to provinces, territories and municipalities, and interest and actuarial losses.

In 2024/25, spending on government programmes is budgeted to amount to C$225bn (C$123bn in operating expenses and C$102bn in transfer payments), while major transfers to persons are expected to be C$135bn (comprising C$80bn in elderly benefits, C$28bn in child benefit payments and C$27bn in employment insurance benefits).

Major transfers to provinces, territories and municipalities in 2024/25 of C$121bn comprise contributions of C$57bn for health care, C$25bn in equalisation payments to provinces, C$24bn for social programmes (social care, social assistance, post-secondary education, early years development, early learning and child care), C$5bn for territories, and C$2bn for community building, net of a C$7bn reduction in payments to Quebec (which acquired a greater share of taxes in the 1960s and 1970s), plus C$15bn in proceeds from pollution pricing returned to Canadians either directly or via provinces and territories.

Not shown in the chart is the projected balance sheet, with net liabilities expected to increase from an estimated C$1,216bn (£715bn) on 31 March 2024 to a budgeted C$1,255bn (£738bn) on 31 March 2025 and a projected C$1,372bn (£807bn) on 31 March 2029. The forecast balance sheet for 31 March 2025 comprises C$117bn (£69bn) in non-financial assets and financial assets of C$719bn (£423bn) less total liabilities of C$2,091bn (£1,230bn).

Net liabilities are expected to increase more slowly than the size of the economy, resulting in the ratio of net liabilities to GDP falling from 42.1% to 41.9% to 39.0% over the same period.

The budget document also reports on the Canadian government’s long-term financial projections, with federal net liabilities expected to reduce to 9.0% of GDP by 2055-56 despite a projected increase in the budgetary deficit back up to 1.1% of GDP. This partly reflects an assumption that net immigration will continue at 0.9% a year, offsetting the effects of more people living longer and a fertility rate of 1.5 births per woman.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, affordable housing is the first area of focus for Budget 2024, with the federal government aiming to increase the number of new homes by 3.87 million by 2031, a net 2 million on top of the 1.87 million already expected to be built.

For more information, read the Canada Budget 2024 website.

For more information about the UK Spring Budget 2024, visit icaew.com/budget.