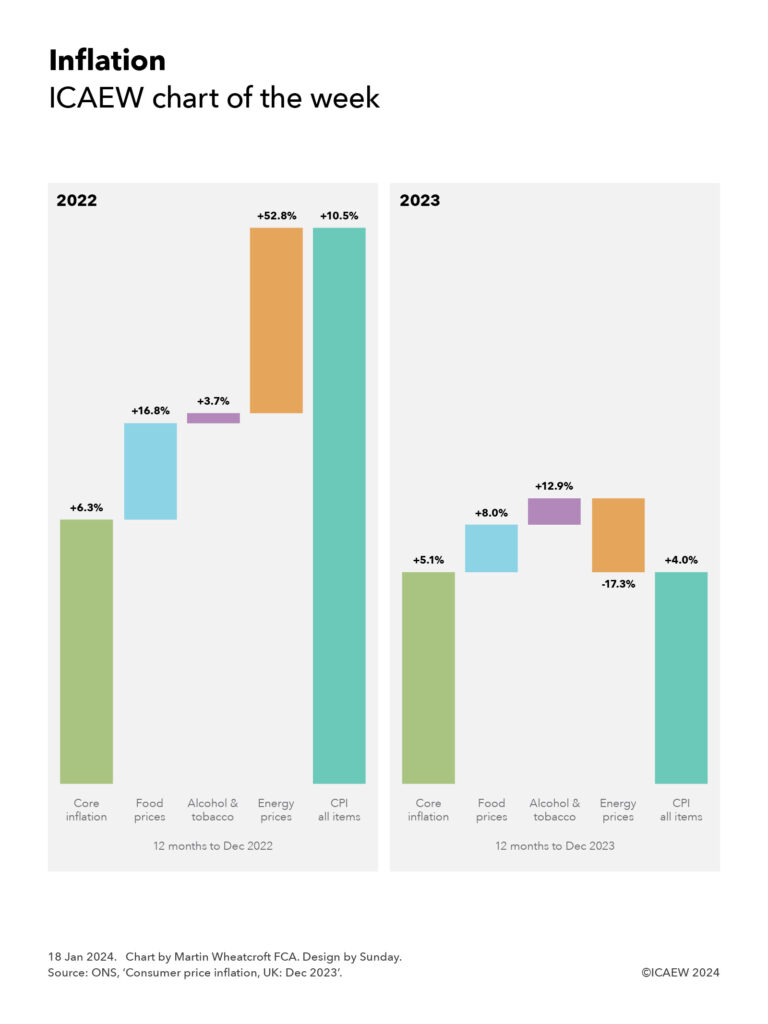

My chart for ICAEW this week illustrates how core inflation has only dropped from 6.3% in December 2022 to 5.1% in December 2023, even as the headline rate has come down from 10.5% to 4.0%.

On 17 January 2023, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) published its latest consumer price inflation (CPI) statistics for the 12 months to December 2023, reporting that headline inflation has fallen to an annual rate of 4.0% compared with 10.5% a year earlier – a more than halving of the annual rate of price growth.

This contrasts with CPI excluding energy, food, alcohol and tobacco (typically described as core inflation), which was 6.3% and 5.1% in the 12 months to December 2022 and 2023 respectively.

The left-hand side of my chart this week illustrates how core inflation in the 12 months to December 2022 of 6.3% contributed just under 5.0% to the weighted average total inflation rate of 10.5%, with food prices up 16.8%, alcohol and tobacco up 3.7%, and energy prices up 52.8% contributing a further 1.8%, 0.2% and 3.5% respectively.

The right-hand side shows the 12 months to December 2023, where core inflation of 5.1%, food price inflation of 8.0%, alcohol and tobacco inflation of 12.9%, and a fall in energy prices of 17.3% contributed approximately 4.0%, 0.9%, 0.5% and -1.4% respectively to the weighted average total rate of consumer price inflation of 4.0%

The relative weightings may explain why many people feel that inflation is still running faster than the headline rate. Food prices, up 8.0% in the past 12 months, have increased twice as fast as CPI of 4.0%, while alcohol (up 9.6%) and tobacco (up 16.0%) have gone up by even more. These may have been offset by energy prices coming down by 17.3% over the past 12 months, but this may not be perceived as that beneficial given how energy is still significantly more expensive than it was before the cost-of-living crisis started.

For policymakers, the bigger concern will be the stickiness in core inflation, which remains stubbornly higher than the Bank of England’s target for overall CPI of 2.0%. While the expectation is that both core and headline rates will come down further during the course of 2024, the Bank is likely to remain cautious about declaring victory in the fight against inflation despite worries about the effects of high interest rates on the struggling economy.

![Exploding debt

Step chart showing how UK public sector net has changed between March 2008 and the projected position in March 2029.

[debt bars shaded orange, changes shaded in purple]

March 2008: £0.6trn

Financial crisis: +£0.7trn

March 2012: £1.3trn

Austerity years: +£0.5trn

March 2020: £1.8trn

Pandemic / energy crisis: +£0.9trn

March 2024: £2.7trn

[bar colours shaded by 50% to indicate the following are projected numbers]

Latest plan: +£0.4trn

March 2029: £3.1trn

30 Nov 2023.

Chart by Martin Wheatcroft FCA. Design by Sunday.

Source: OBR, 'Public finances databank - Nov 2023'.](https://martinwheatcroft.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/icaewchart286debt-768x1024.jpg)