Council finance teams put a lot of time and resources into preparing financial statements each year but often the results are impenetrable. A focus on streamlining and clarity can make a huge difference, writes the ICAEW’s public sector director.

Getting the annual accounts finished and out of the way is a relief to most finance teams. It is a major undertaking to put together what can be a couple of hundred pages of detailed numerical content and getting your auditors to sign off on it all. Understandably, there is a temptation to just upload it to the website, forget about it for another year and move onto the budget, that bid for levelling up funding, or the many other priorities that are pushing up your to-do list.

But are you getting a full return on the investment you make into your annual report? The answer is almost certainly “no”. Unlike their corporate equivalents, local authority accounts are notoriously “impenetrable” and a difficult tool to use in communicating with stakeholders on the financial story of the year and how you are making progress in delivering on your strategic objectives.

The last thing you want to do is to use a long, complicated, and difficult to understand document as a tool for accountability, while for readers the challenge in trying to understand the finances of many local authorities is daunting. Ahead of them might be a 250-page document with over 150 pages of difficult-to-follow financial statements. To put it bluntly, who has the time to read all of that?

Concise and streamlined accounts

This contrasts with annual reports such as that recently published by the Government Legal Department (a non-ministerial department), where the financial statements including notes take up only 15 pages of an 80-page document. This is a much better vehicle for understanding the financial performance and position of, admittedly, a simpler organisation than most local authorities – but an example of how being concise and streamlined can make accountability that much easier to achieve.

It is almost two years since the conclusion in the Redmond Review that local authority accounts are “considered impenetrable to the public”. As finance leaders in the local government sector, this should concern us all.

Your accounts should help residents, councillors and councils understand the financial performance and position of the local authority. They should be the cornerstone of the evidence-based decision-making and strong financial management, essential for effective delivery of public services.

Unfortunately, impenetrable financial reports achieve none of the benefits that a well-designed annual report is capable of. Not only do they sap the resources of finance teams in preparing information that is not going to be used effectively, but they mean other ways have to be found to provide the financial transparency that councillors and others need to represent the interests of local residents effectively. Or (as many councillors tell us) not to have a full understanding of the finances at all.

Don’t wait for CIPFA/LASAAC Code improvements

While there is a real need to reform the Local Authority Accounting Code and the example financial statements in the code guidance notes – and CIPFA/LASAAC are working on that – there is no need to wait for that to happen. Yes, the complexity of the local authority finance system doesn’t help, but even so I have yet to read a set of local authority financial statements where I did not think there was something that the preparers could have done to make them more understandable and concise, while remaining compliant with the code.

Some local authorities have already been able to streamline their financial statements to good effect. Fife Council, for example, has been able to reduce the length of its annual report including the management commentary to only 68 pages, while Southwark Council worked with its auditors to reduce their document to 133 pages, which is notably short for a large London borough.

One mistake is to treat the example financial statements as currently devised as a template, rather than as a reference document covering almost every conceivable scenario. We too often see local authorities including boilerplate disclosures from the example financial statements even when not relevant. CIPFA has published helpful accounts streamlining guidance that advises moving away from the example financial statements to reduce the length of the report.

It is important though when conducting a streamlining exercise that you consider the needs of users. Shorter for the sake of it is counterproductive if it means the accounts are non-compliant or even more difficult to understand. For example, nothing useful is achieved by tiny font sizes or merging notes that don’t relate to each other.

Consider instead how you can structure your financial statements effectively. For example, in most circumstances there is no need for three separate notes to the cash flow statement when there is room in the primary statement itself. Could you move the more detailed financial instrument and pension disclosures to the back of the report so that the main balance sheet notes flow together more seamlessly? Have you “weeded” your accounting policies note as much as you can? It is surprising how many local authorities report a policy for contingent assets when there are none that (apparently) need disclosing.

Think about what users require

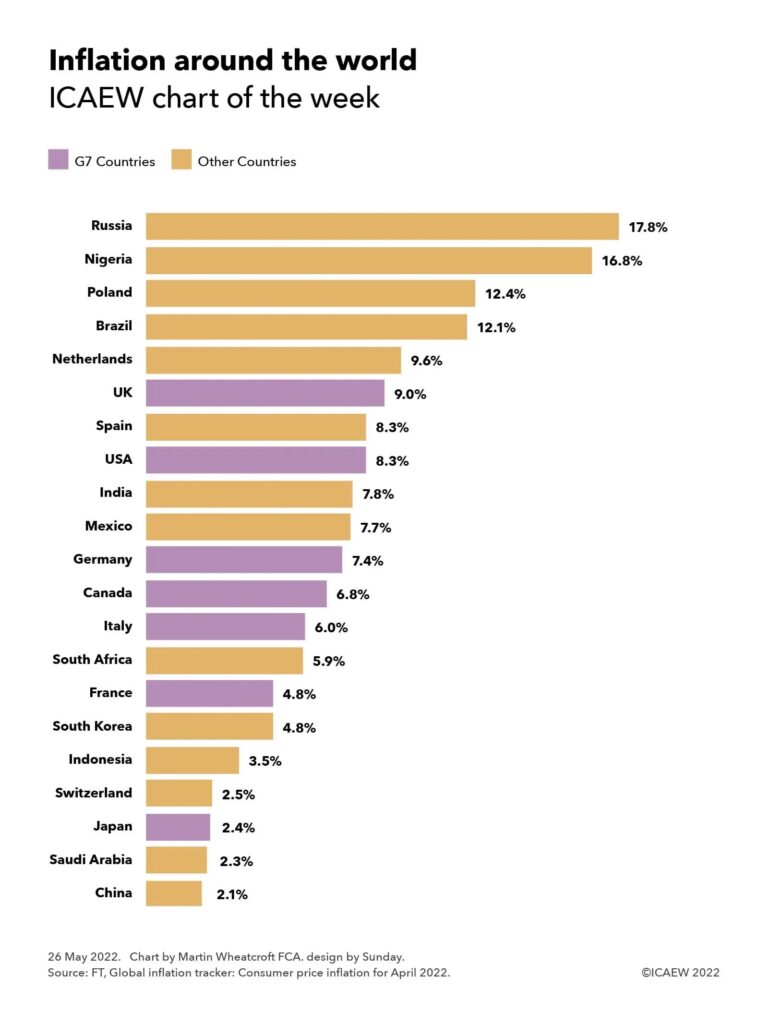

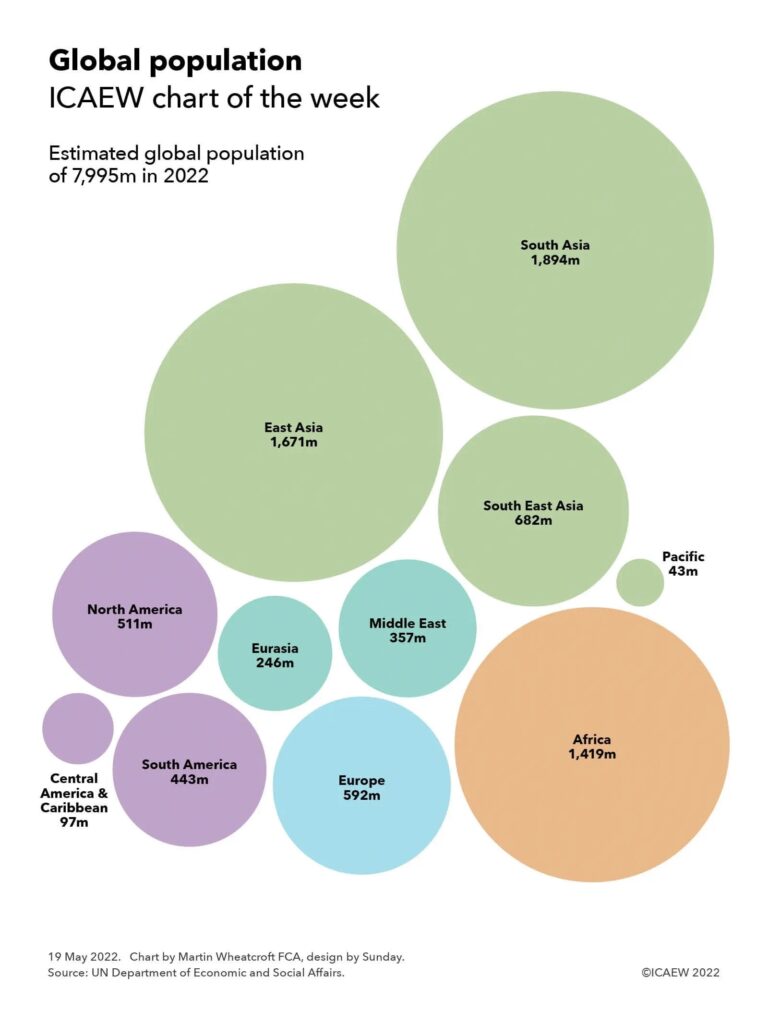

Streamlining should not mean losing important information – instead, it gives an opportunity to focus on what is important. Take out accounting policies that merely restate GAAP, or long expositions of credit risk on immaterial exposures that do not aid understanding, and instead provide more insightful disclosures that are specific to your local authority, perhaps such as the financial performance of council-owned businesses. Tables and charts can be used to communicate concisely, without compromising on the quality of the information provided.

Have you provided what is really needed, such as why investments have been recognised at amortised cost rather than fair value (or vice versa)? Or how you have calculated your Minimum Revenue Provision (MRP)? Despite its importance to council tax calculations, a recent review of a sample of local authority accounts by the ICAEW found that many did not disclose the MRP policy or the key judgements made in its calculation and, in the few instances where there was disclosure, the language used was often so technical as to be incomprehensible. Getting rid of jargon can help make it easier for councillors and residents to use the accounts.

A foundation for financial conversations with stakeholders

Local authorities are in theory much more transparent than their private sector comparators. Listed companies do not have to publish their budgets or internal financial reports, debate their financial decisions in meetings open to the public, nor allow their stakeholders the ability to inspect their detailed books and records.

Despite that we often hear the view that local authority finances are much more difficult to understand – a classic example of how greater quantity does not equal better quality.

Making the annual report and accounts a foundation for your financial communication is one way of addressing the deficit in understanding, and a way of getting a better return on all the effort you put into them. A good annual report should be an annually updated reference work that is actively used as the go-to place to find your strategy, how you monitor progress against your objectives, how you are managing risks, and the strength (or otherwise) of your financial position, as well as telling the story of the year in words and numbers.

Doing so may also help you get on the front foot with the new Office for Local Government, which is likely to become an avaricious consumer of your performance data once it gets up and running.

While we hope CIPFA/LASAAC’s project to improve the presentation of local authority financial statements will put understandability at its heart, that does not mean you should wait for developments. Not only can you make your annual report that much more usable through streamlining disclosures and improving clarity (potentially saving time by making it easier to prepare in the future), but you have an opportunity to use it to support better quality dialogue with your stakeholders.

If you don’t feel comfortable in presenting your annual report to your councillors as the one financial document that they need to read each year, then I would suggest that you are not doing it in the right way.

This article was originally published in Room 151.