22 January 2020: The BBC’s finances are in the spotlight for this week’s chart, as it struggles to generate the income it needs to fund its public service broadcasting mission.

A National Audit Office report out this week on the BBC’s strategic financial management highlights the financial pressures facing the BBC as it seeks to deliver on its universal public service broadcasting obligation in the face of a rapidly changing media landscape.

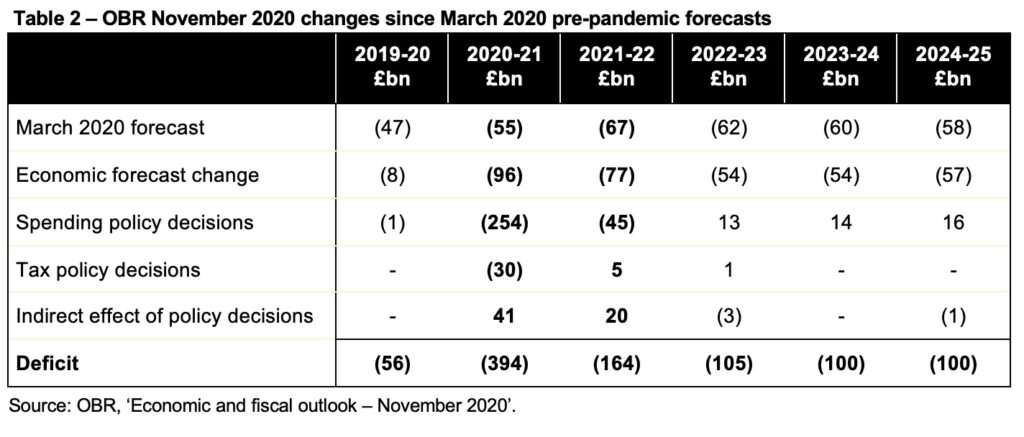

The #icaewchartoftheweek illustrates how the BBC generated revenue of £4.9bn in the year ended 31 March 2020. This is less than the £9bn or so generated by Sky in the UK & Ireland each year, but more than ITV’s £3bn or Channel 4’s £1bn.

The principal source of income is the TV licence fee, which generated £3.2bn in 2019-20 from 21.2m households. This excludes 4.5m households that received free licences, with the government providing £253m to cover this in addition to an £87m grant for the World Service. Other income generated by the public service broadcasting arm amounted to £0.2bn, while BBC Studios and other commercial activities had external revenues of £1.2bn.

Expenditure of £5.0bn included £4.0bn incurred on public service broadcasting, paying for eight TV channels and 60 radio stations in the UK, radio services around the world in more than 40 languages and extensive online services – most notably BBC iPlayer.

The BBC’s domestic TV and radio channels cost £1,609m and £494m respectively, while £238m was spent on BBC Online and £315m on the BBC World Service, of which £228m was funded from the licence fee. £204m was incurred on other services (including a contribution to S4C), while distribution, support and other costs incurred amounted to £1,070m, excluding £119m of licence fee collection costs.

A colour TV licence in 2019-20 cost £154.50, equivalent to £12.88 per month and the BBC estimates that £6.83, £2.22, £1.24 and £1.24 of each licence fee went on TV, radio, BBC Online and the World Service respectively, while £1.35 paid for other services, distribution and support, licence fee collection and other costs.

Commercial activities contributed £176m to the bottom line, providing a small subsidy to licence fee payers, with attempts by the BBC to start a global subscription service for British TV content in partnership with ITV (Britbox) yet to bear much fruit. The principal commercial revenue stream remains sales by BBC Studios to broadcasters around the world, together with advertising from the seven UKTV channels now wholly owned by BBC Studios and declining amounts from DVD sales.

At the bottom line, the BBC incurred a loss of £119m in 2019-20, following on from a loss of £69m in the previous year and a profit of £180m in 2017-18. An improved contribution from commercial activities was not enough to offset the cut in the government funding for free TV licences for over-75s, which fell from £656m in 2017-18 to £253m in 2019-20. This funding has now ceased and from 1 August 2020 the BBC reintroduced licence fees for around three million over-75s households, retaining free licences for 1.5m or so over-75s households receiving pension credit (a welfare benefit for pensioners on low incomes).

There is a lot of debate both inside and outside the BBC about the future of the licence fee model and whether it can survive in a landscape of global streaming services. As it approaches its 100th anniversary in October 2022, the BBC will be hoping it can find a way to extend its public service broadcasting mission for a second century.