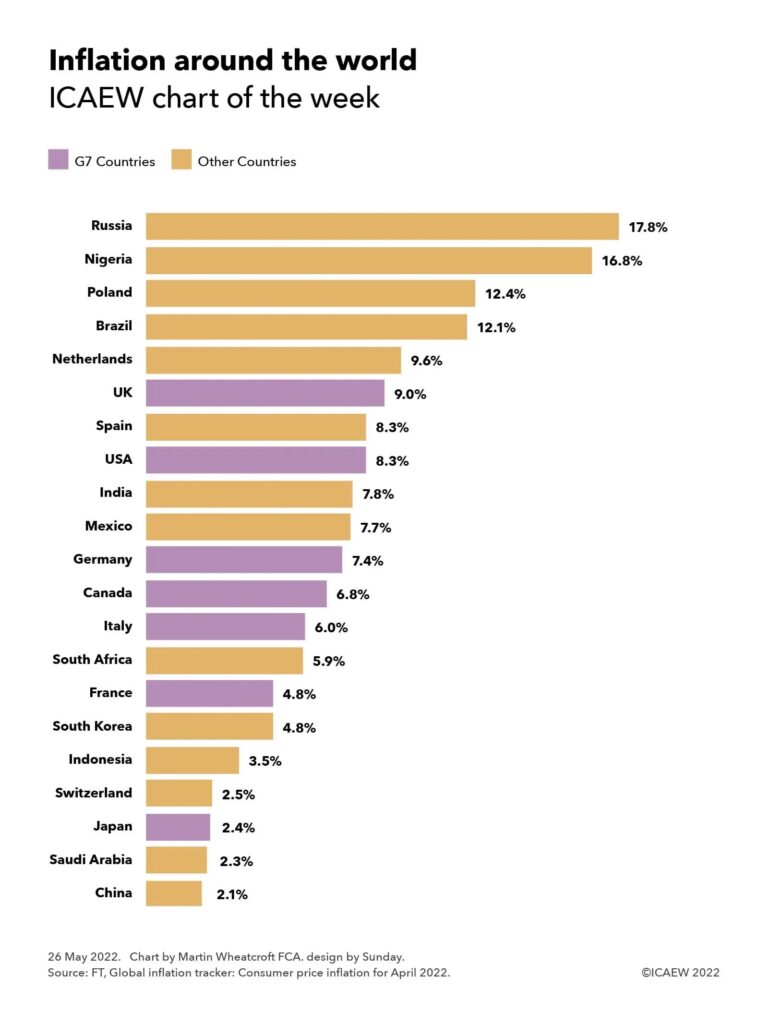

This week we look at how inflation is racing upwards across the world, with the UK reporting in April one of the highest rates of increase among developed countries.

Inflation has increased rapidly over the last year as the world has emerged from the pandemic. A recovery in demand combined with constraints in supply and transportation has driven prices, with myriad factors at play. These include the effects of lockdowns in China (the world’s largest supplier of goods), the devastation caused by the Russian invasion in Ukraine (a major food exporter to Europe, the Middle East and Africa), and the economic sanctions imposed on Russia (one of the world’s largest suppliers of oil and gas).

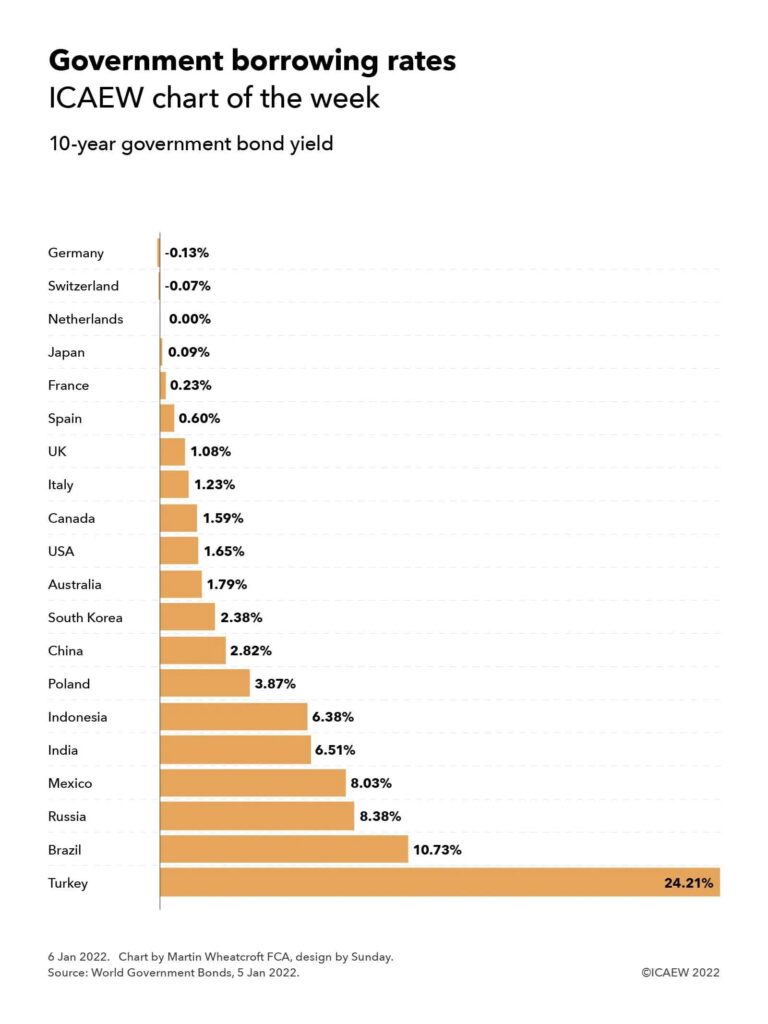

As the chart shows, the UK currently has – at 9% – the highest reported rate of consumer price inflation in the G7, as measured by the annual change in the consumer prices index (CPI) between April 2021 and April 2022. This compares with 8.3% in the USA, 7.4% in Germany, 6.8% in Canada, 6.0% in Italy, 4.8% in France and 2.4% in Japan.

The UK’s relatively higher rate partly reflects the big jump in energy prices in April from the rise in the domestic energy price cap, which contrasts with France, for example, where domestic energy price rises have been much lower (thanks in part to state subsidies). The UK inflation rate also hasn’t been helped by falls in the value of sterling, making imported goods and food more expensive.

Other countries shown in the chart include Russia at 17.8%, Nigeria at 16.8%, Poland at 12.4%, Brazil at 12.1%, Netherlands at 9.6%, Spain at 8.3%, India at 7.8%, Mexico at 7.7%, South Africa 5.9%, South Korea at 4.8%, Indonesia at 3.5%, Switzerland at 2.5%, Saudi Arabia at 2.3% and China at 2.1%. For most countries, the rate of inflation is substantially higher than it has been for many years, reflecting just how major a change there has been in a global economy that had become accustomed to relatively stable prices in recent years.

This is not the case for every country, and the chart excludes three hyperinflationary countries that already had problems with inflation even before the pandemic, led by Venezuela with an inflation rate of 222.3% in April, Turkey with a rate of 70%, and Argentina at 58%.

Policymakers have been alarmed at the prospect of an inflationary cycle as higher prices start to drive higher wages, which in turn will drive even higher prices. For central banks that has meant increasing interest rates to try and dampen demand, while finance ministries have been looking to see how they can protect households from the effect of rising prices, particular on energy, whether that be by intervention to constrain prices, through temporary tax cuts, or through direct or indirect financial support to struggling households.

Here in the UK, both the Bank of England and HM Treasury have been calling for restraint in wage settlements as they seek to head off a further ramp-up in inflation. They hope that inflation will start to moderate later in the year as price rises in the last six months start to drop out of the year-on-year comparison and supply constraints start to ease, for example as oil and gas production is ramped up in the USA, the Middle East and elsewhere to replace Russia as an energy supplier, and as China emerges from its lockdowns.

Despite that, prices are likely to rise further, especially in October when the energy price cap is expected to increase by 40%, following a 54% rise in April. This is likely to force many to make difficult choices as household budgets come under increasing strain.

After all, inflation is much more than the rate of change in an arbitrary index; it has an impact in the real world of diminishing spending power and in eroding the value of savings.