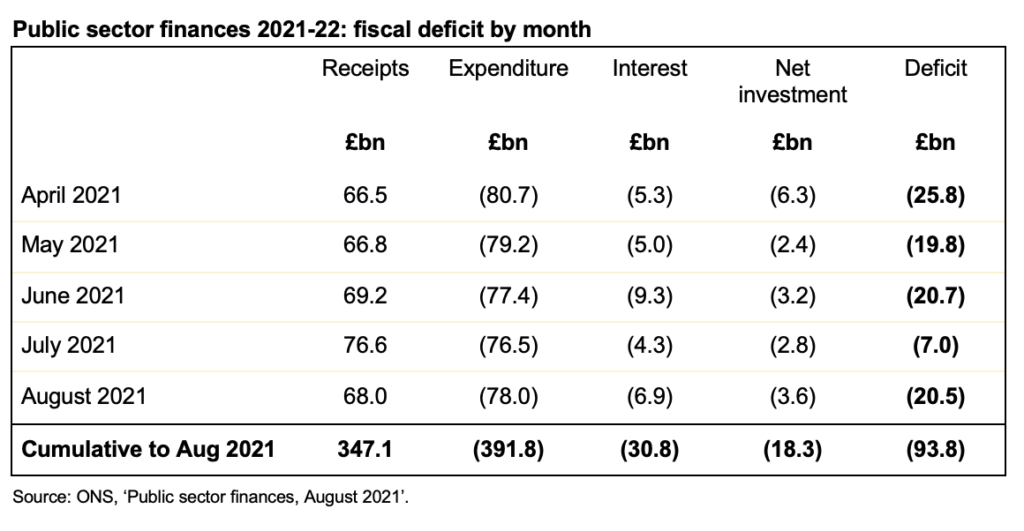

The Spending Review and Autumn Budget will mark the first step in the Chancellor’s plan to bring the public finances back under control following the pandemic. There are significant challenges to be overcome if he wants to do so.

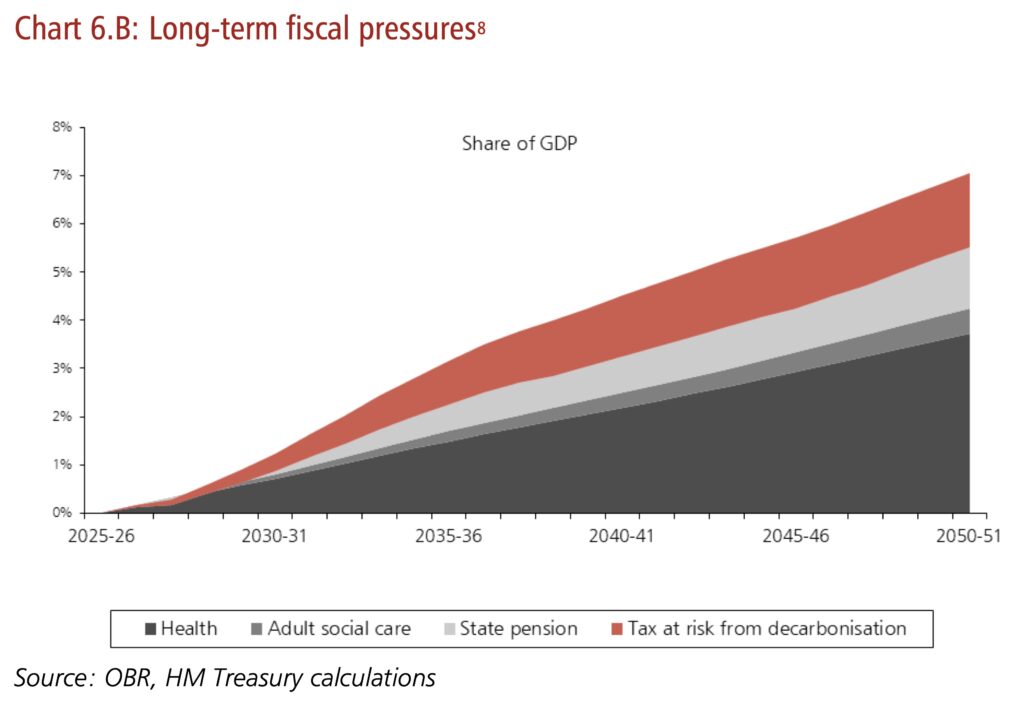

Tucked away on page 91 of HM Treasury’s Net Zero Review Final Report published on 19 October is a chart illustrating the main long-term pressures on the public finances. This describes how fiscal pressures from health, adult social care, the state pension and tax at risk from decarbonisation could amount to 7% of GDP by 2050-51, equivalent to over £150bn a year in ‘today’s money’.

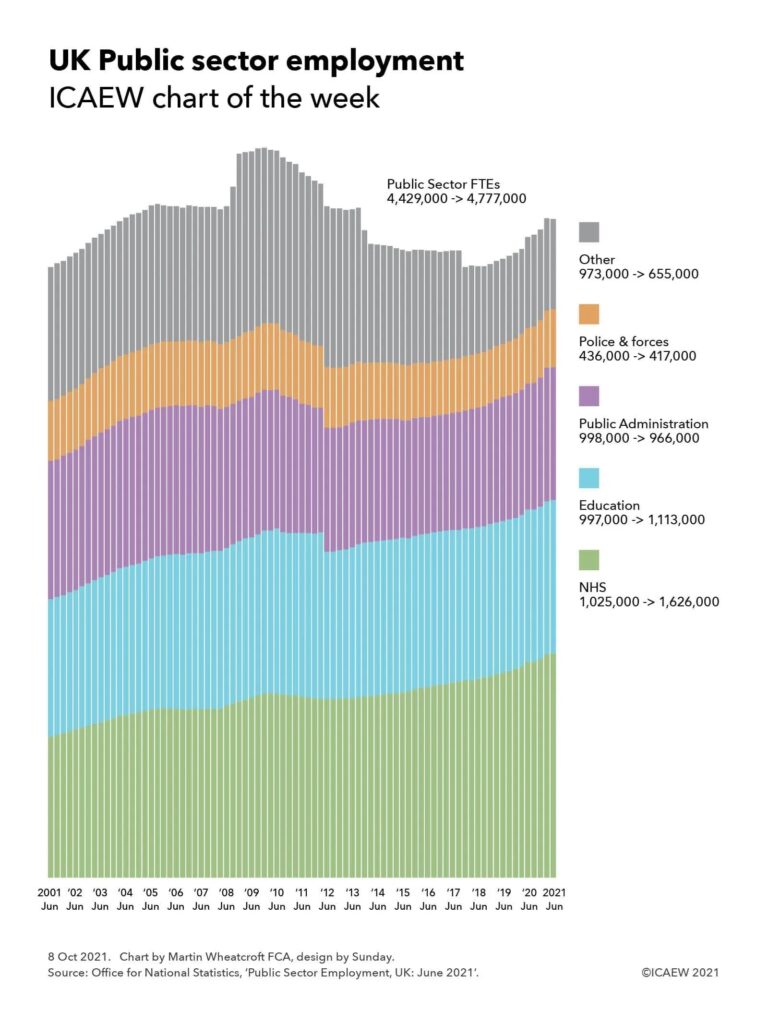

The majority of the fiscal pressures identified (5.5% of GDP in 2050-51) relate to structural factors, or what can better be described as more people living longer, sometimes less healthy lives. This will add significantly to the costs of healthcare, adult social care, and the state pension over the coming decades – big drivers of public spending.

The pay-as-you-go nature of the UK welfare state means that the tax and national insurance contributions made by people through their working lives to fund these services are not saved up and invested but are instead spent on previous generations. Consequently, there is (unlike some other countries) no pot of money from which to draw on to fund retiree pensions, health, or social care. Instead, taxpayers will be called on to cover these costs as they arise.

More spending cuts are unlikely to be sufficient to close the gap

One option might be to offset rising costs by cutting public spending in other areas, as has already happened with the defence budget, where cuts from over 10% of GDP half a century ago to under 2% of GDP today have helped to offset increases in the funding allocated to the National Health Service.

However, with defence and security spending together hovering just above the 2% NATO minimum, and a decade of austerity that has seen significant cuts in both public services and welfare budgets, the unfortunate reality is that there are no other significant budget headings that the Chancellor might look to dip into to meet these long-term fiscal pressures. At least not without a very radical restructuring of the state, which does not appear to be on the cards.

In practice, Rishi Sunak will have a hard enough time addressing short-term fiscal pressures in other areas. A key example is the criminal justice system, where cuts in spending in recent years on the police, courts, prosecutors, and legal aid have together contributed to significant delays and lost opportunities to prosecute criminals, just as crime levels rise and it returns to the political agenda. A backlog of cases built up over the course of the pandemic doesn’t help. More money beyond that already allocated to restore police numbers is likely to be needed, but where can it be found?

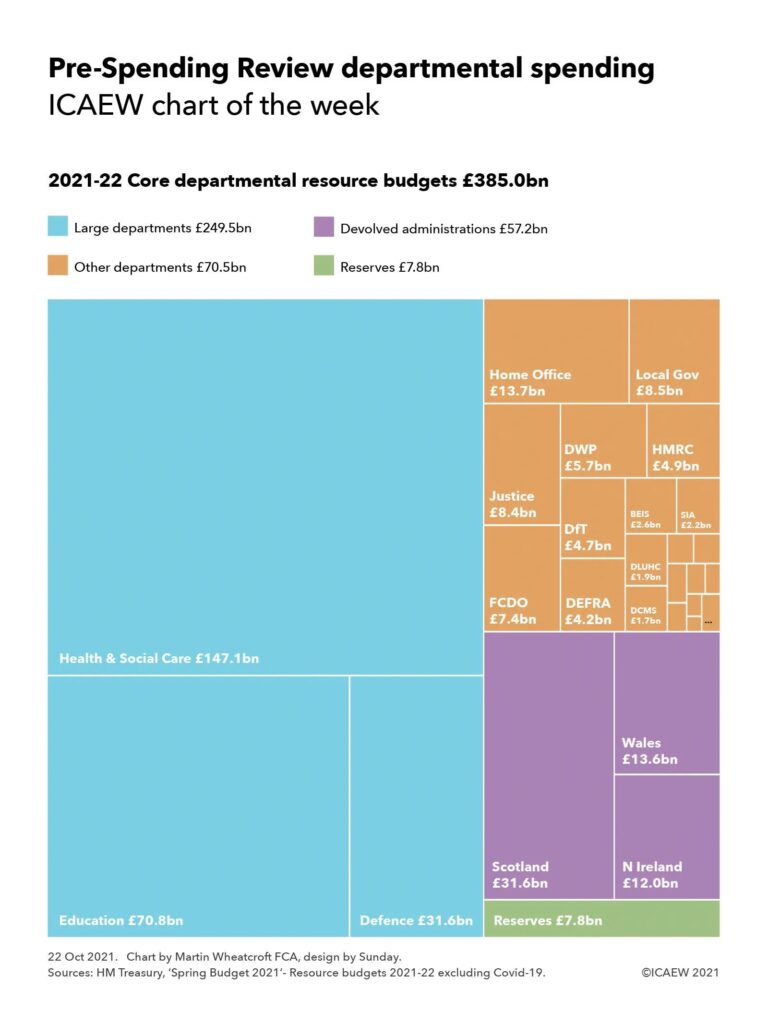

Everywhere the Chancellor looks there are difficult choices between the spending needed to meet policy priorities such as levelling up (local authorities, education and transport), Global Britain (FCDO and international trade), and Build Back Greener (energy and transport), as well ensuring the day-to-day operations of both central and local government continue – from collecting the bins to repairing the roads to defending the country.

There are opportunities to save money through being more efficient, but it is important to understand that administration costs are a relatively small proportion of overall public spending and that many UK public services such as the NHS are fairly cost-effective when compared with equivalents in other countries. Technological change including AI and medical developments could have a significant impact in reducing costs, but it is unclear that they could produce anywhere near the level of service improvement that would offset the long-term fiscal pressures. Ironically, medical developments could also increase those pressures, with savings in the cost of healthcare treatments being offset by helping us live even longer lives. Good news but adding to the public finance challenge.

The demands from across government for more money are intense, putting the Chancellor under severe pressure to increase the overall spending envelope – not just in the next financial year or three, but permanently adding to budgets forevermore.

Can the long-term fiscal pressures be avoided?

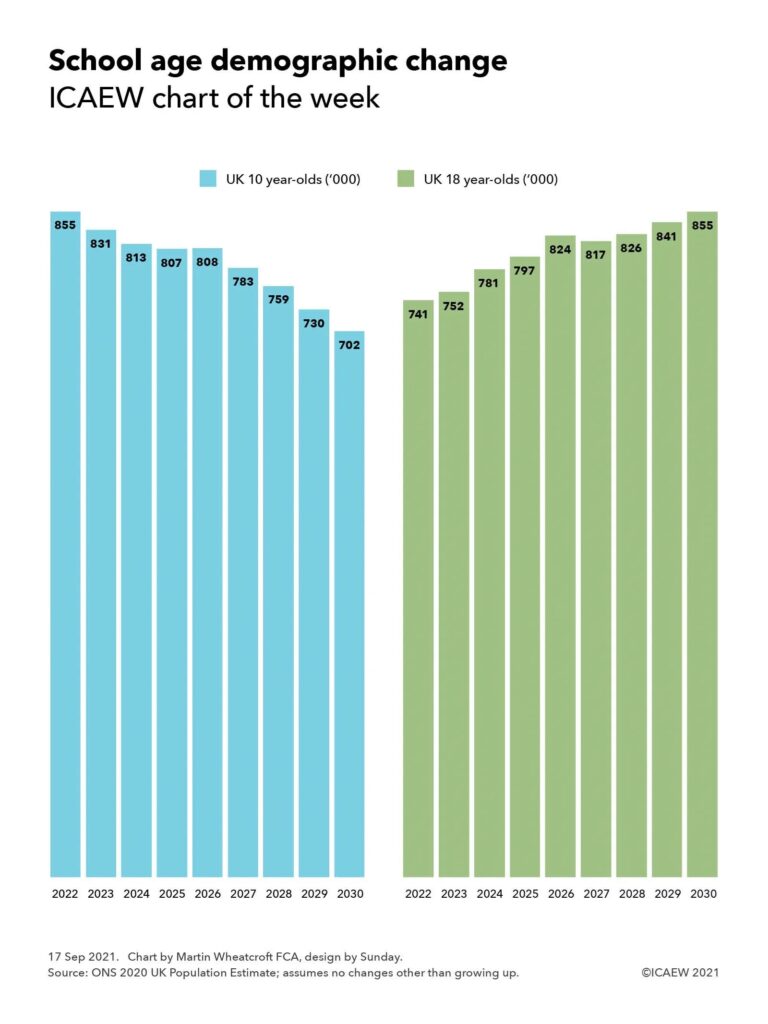

The main driver for most of the long-term fiscal pressures identified by HM Treasury is longevity, with the number of people aged over 70 expected to increase by 58% over the next 25 years at the same time as the number of people under the age of 70 (including those of working age who pay most of the taxes) is expected to increase by only 2% or potentially fall by 7% if inward migration falls.

There are some things that can be done to mitigate these increases to a certain extent, such as permanently abandoning the triple lock that has driven substantial increases in the level of the state pension over the last decade. However, this could be politically difficult, as well as not necessarily achieving the intended goal of saving money if more pensioners end up needing support from the welfare system. A more likely approach would be to further increase retirement ages as recently recommended by the OECD.

Other options that have been suggested include greater rationing of health care or introducing charges for some medical procedures. Such moves could help offset some of the pressures on health care spending but would be politically difficult as well as adding an extra layer of complexity to the welfare state. Those who can afford to pay would not only pay more, but there would still be a need to pay more in taxes to fund those on low incomes who wouldn’t be able to afford the additional costs without help.

One of the long-term pressures identified by the government – the effect of decarbonisation on tax receipts – is not really a pressure and arguably should not be included in the list.

While in theory the £37bn a year raised in fuel duty, vehicle excise duty and other taxes will disappear if transport is successfully decarbonised, this is a tax burden already being incurred by road users. All that is likely to happen is a change in the tax used to collect that money, with road charging the most likely option identified so far. This may be seen as a tax rise by some, particularly those hoping that the low tax status of electric cars and other zero emission vehicles might continue into the future, but the net effect is likely to be a temporary tax rise over the course of the transition as the existing taxes co-exist with the new, hopefully adding to the incentive to decarbonise without having to increase taxes in other areas.

Borrowing has a role, but can’t take all the strain

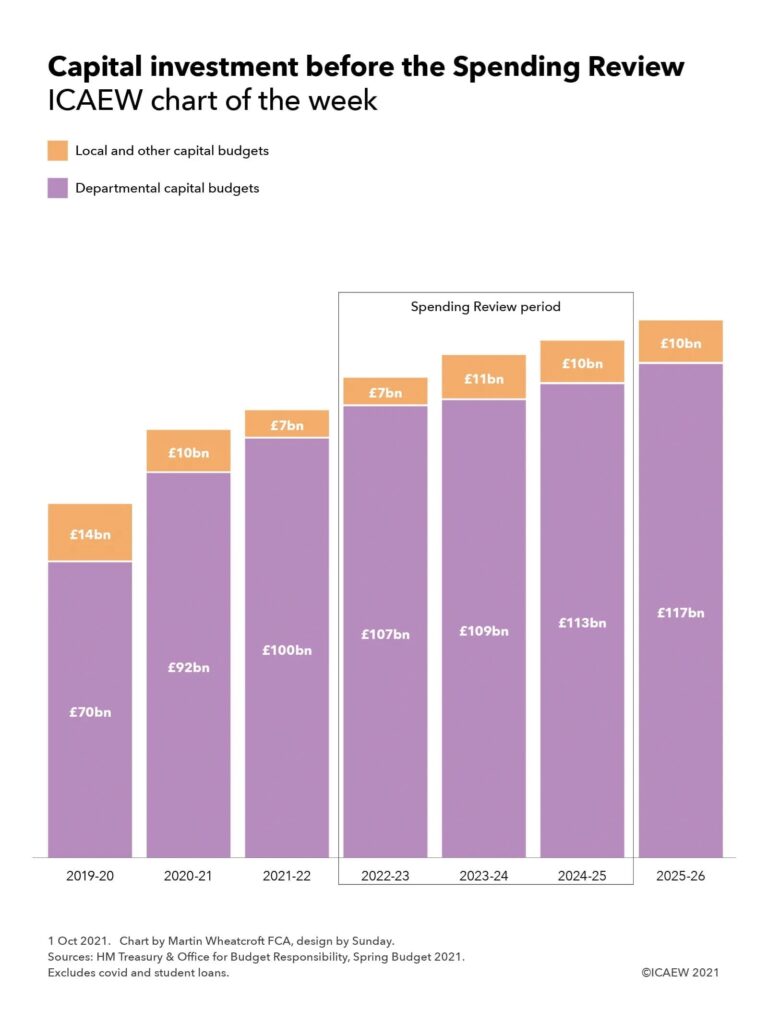

The benefit of being a sovereign nation is the ability to raise money from debt markets at much lower interest rates than those available to businesses or individuals. This is invaluable, as there are often good reasons to borrow to fund capital investment, which in turn will often generate more economic activity and enhance future tax revenues.

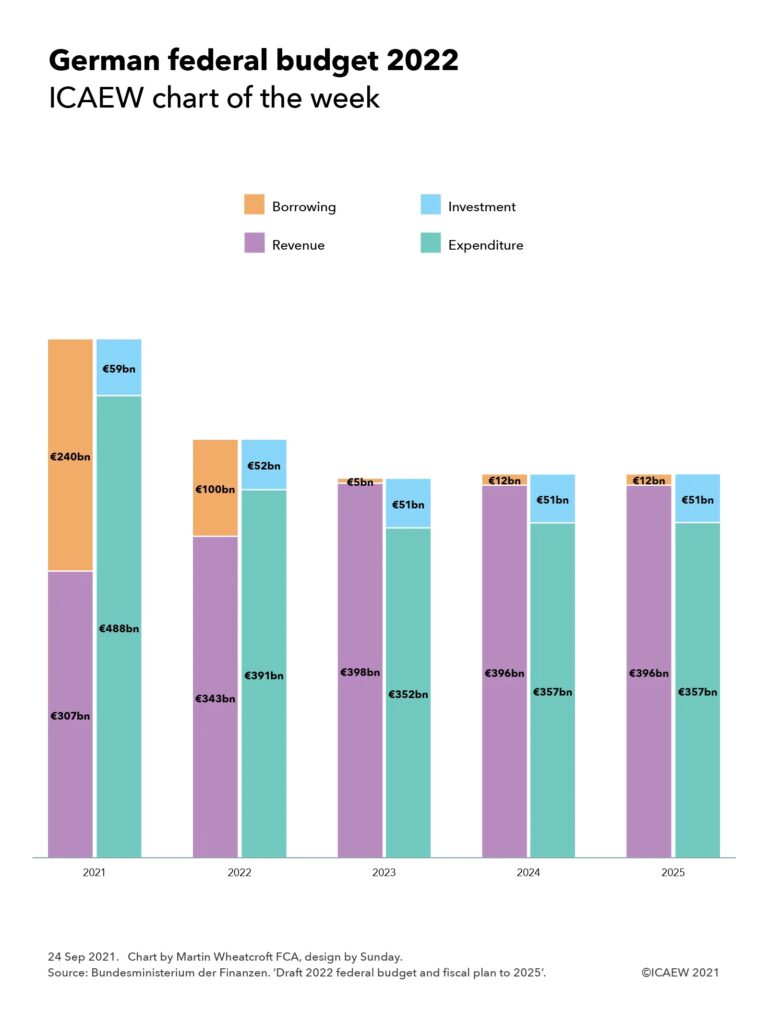

However, governments in developed countries have routinely used borrowing to make up for shortfalls between revenues and current spending in the hope that growth in the size of the economy will inflate away the debts built up this way.

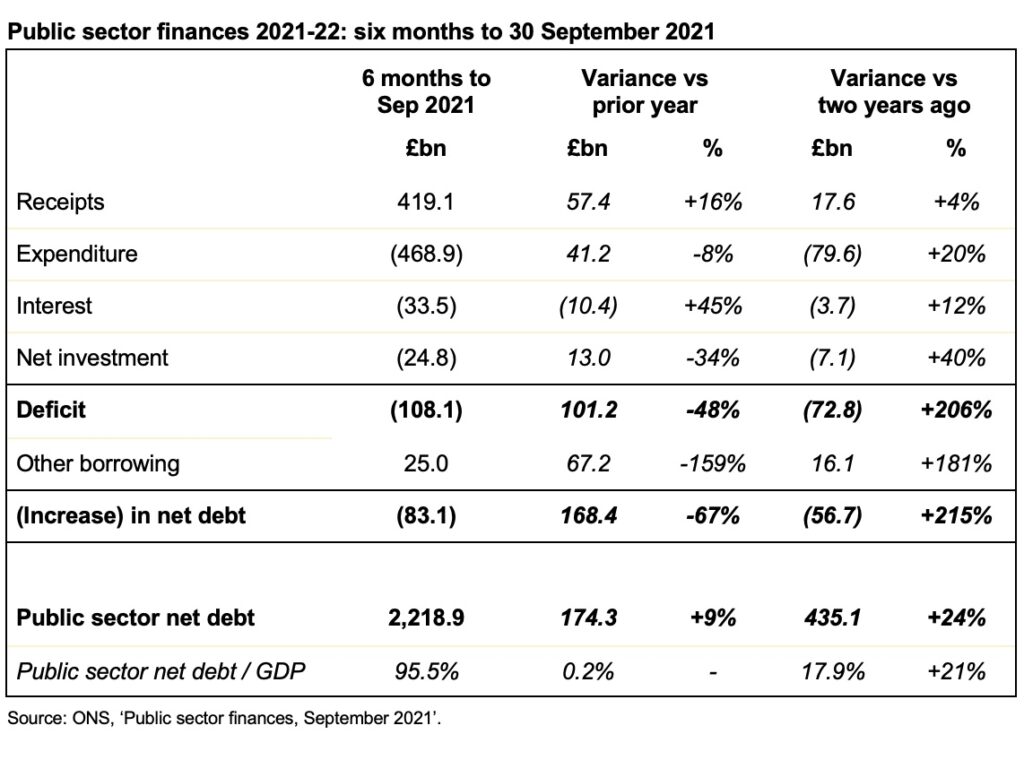

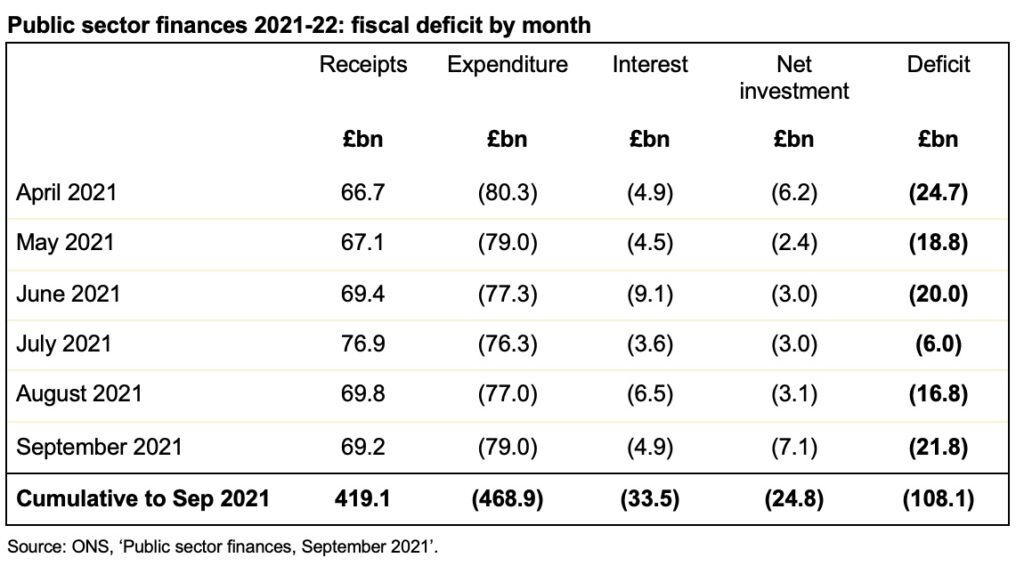

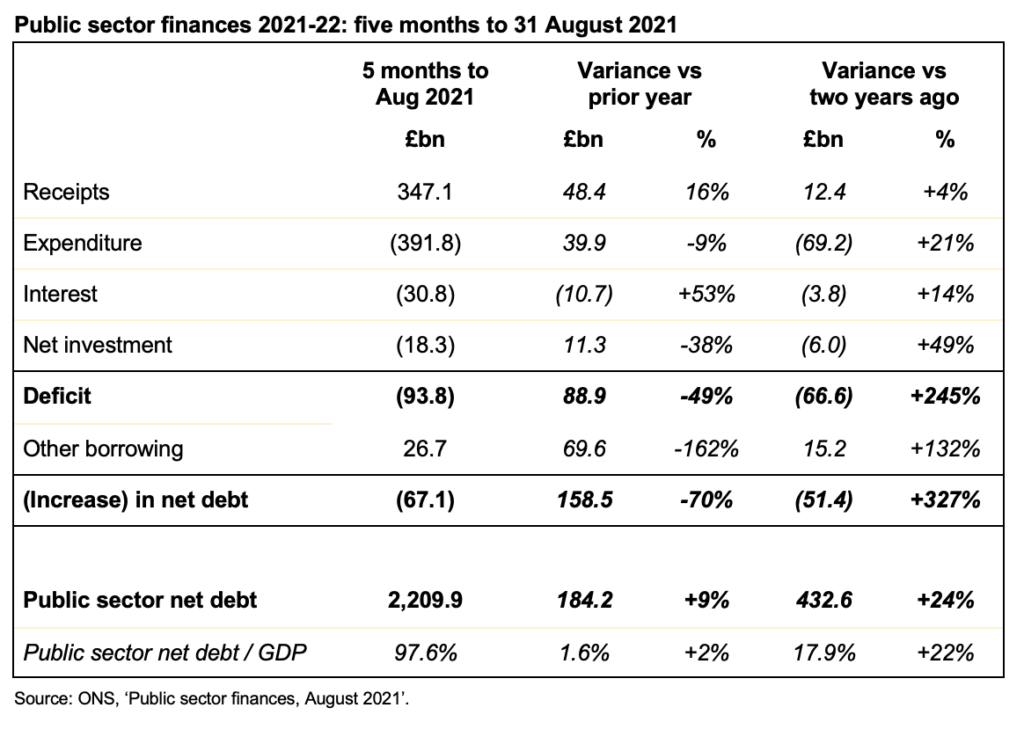

The financial firepower provided by borrowing has enabled the UK to support the economy and fund public services and welfare through the financial crisis just over a decade ago and the pandemic in 2020 and 2021. However, the consequence has been to increase public sector net debt from around less than £0.5tn or 35% of GDP in 2008 to £1.8tn or 80% in 2019 and to £2.2tn or just over 95% of GDP as of today.

This excludes £2.5tn or so of other liabilities in the public balance sheet, such as for unfunded public sector pension obligations, nuclear decommissioning obligations and clinical negligence liabilities. When added to debt these take public sector liabilities to more than double the size of the economy.

Countries such as Japan have even higher levels of debt than the UK which, in theory at least, might indicate that the UK government has headroom to borrow even more, this is dependent on the continued confidence of capital markets. The Chancellor is therefore aiming to bring down the ratio of debt to GDP gradually over time, with new fiscal rules designed to ensure that the government targets a balanced current budget by the middle of the decade so that borrowing is only used to fund investment spending.

A particular concern for the Chancellor will be the increased exposure of the public finances to higher inflation and interest rates, which has the potential to claw back any savings he does manage to find in his search for a more efficient government machine.

This is because the current scale and profile of public debt makes it more difficult for the government to ‘inflate away’ debt over time, with the higher interest rates that would be expected to accompany higher levels of economic growth resulting in higher debt-interest costs. Similarly, the effect of higher inflation in increasing nominal GDP and hence reducing the debt to GDP ratio will be offset by the associated uplift in the amounts owed to holders of index-linked gilts.

Economic growth should generate higher tax revenues, but by how much?

The favoured route to bring in more money through the tax line would be through faster economic growth, and the OBR’s October 2021 forecasts are likely to reflect a sharper rebound from the pandemic than was expected in March – providing the Chancellor with more room for manoeuvre, at least in the short term.

Improving productivity is a challenge for governments across the world, while economists have suggested that the combination of Brexit and COVID-19 will make the UK economy permanently 3% smaller than it would have been otherwise. Despite that, higher levels of capital investment within the existing spending plans should have a positive effect on growth, especially if the substantial additional private investment envisaged as part of the Net Zero Strategy is successfully obtained.

The good news is that even moderate levels of economic growth will help put the public finances in a better place, providing capacity for the Chancellor or his successors to be slightly more generous on spending or perhaps fund some limited pre-election tax cuts. The bad news is that even healthy periods of economic growth tend to be punctuated by recessions every decade or so.

Hence the need for prudence in spending plans – if we don’t know how much we (as a country) are going to earn, it makes sense to be careful in our outgoings.

But, there is a risk that too much prudence could result in cutting back on the spending that is needed to drive future prosperity, whether that be funding for education and apprenticeships to enhance skills, or investment in infrastructure to drive regional economic growth. And spending restraint in other areas, such as policing and the criminal justice system, can have other adverse consequences too.

Economic growth is needed to ensure the public finances are brought back under control. Absent an unexpected economic boom, growth on its own is unlikely to provide sufficient tax receipts to fund all of the long-term fiscal pressures identified by the Treasury.

Can further tax rises be avoided?

The introduction of the health and social care levy on top of the tax rises announced in the March 2021 Spring Budget shouldn’t have been a surprise given the long-term pressures on the public finances. The pandemic may have accelerated the arrival of new taxes, but more funding from taxpayers was always the most likely outcome at some point over the next few years.

This is not just because the pandemic has exacerbated the financial situation, but because only very strong levels of economic growth would have enabled any government to avoid putting up taxes. Indeed, the Institute for Fiscal Studies believes that the health and social care levy may have to be increased further by the end of the current decade from 1.25% to 3.15%.

There are some actions the government can take to delay the inevitable, such as increasing labour participation rates, so increasing the pool of taxpayers. But, in the medium- to long-term, the government needs to acknowledge the pressures on public spending and think about how it should go about increasing taxes in a gradual and stable way rather than the current approach of deferring the problem until the pressures become too great.

One thing the government could do better at is developing a long-term tax strategy setting out how it plans to increase taxes gradually over time, avoiding the need for sudden changes, such as the introduction of the health and social care levy with only six months’ notice or the almost one-third rise in the corporation tax rate from 19% to 25% that comes into force on 1 April 2023.

A long-term fiscal strategy is needed to put the public finances on a sustainable path

Tax is not the only aspect of the public finances that would benefit from a longer-term approach. A fiscal strategy encompassing tax, spending, borrowing, debt, and the wider public balance sheet is essential if the government is to improve resilience of the public finances to future economic shocks and put them on a sustainable path.

Such a strategy should address the long-term pressures on public spending as part of a practical vision for the public finances over the next 25 to 50 years. It would consider how best to fund public services over time and how to strengthen the public balance sheet.

At a more granular level it would look at issues such as the unfunded nature of many public sector liabilities, for example considering whether premiums could be levied to fund investments to cover clinical negligence liabilities, rather than rely on there being capacity in future health budgets to cover these costs. Another example would be to consider whether there is a role for sovereign wealth funds, similar to Australia’s Future Fund or Norway’s Oil Fund. It could be argued that some of the savings to the exchequer from ultra-low borrowing rates might have been better used to fund investments for the benefit of future generations instead of being used to cover day-to-day spending, avoiding difficult decisions that should have been addressed earlier.

More significantly, a fiscal strategy would consider how to introduce more long-term thinking into the public finances, moving beyond short-term fiscal rules that have often been broken and prioritising investment that provides positive economic, social and environmental benefits to all of us. It could also provide a framework within which to tackle some of the structural problems in the public finances, such as tax devolution and the complexity of funding streams within and between central and local government, or in clarifying the often misunderstood financial compact between government and citizens.

Reasons to be cheerful

The challenges facing the public finances are significant. According to the Office for Budget Responsibility they are on an unsustainable path. Public debt has increased from less than £0.5tn to more than £2.2tn in less than a decade and a half. Other public sector liabilities amount to least as much again. Cuts in public spending have affected some public services adversely, and the pressure for more spending is intense. Poverty remains and many families struggle financially, further adding to pressures on the government to help. The productivity puzzle remains unresolved and there are significant uncertainties about the health of both the UK and global economies. Tax rises appear inevitable.

However, government has demonstrated in both the financial crisis and the pandemic just how much it can do to support business, individuals, and public services through difficult times when it needs to. Public investment is increasing. Technological developments are helping to improve public services and increase efficiency. The government now knows what is in the public sector balance sheet and is taking steps to improve how it is managed. There is a strategy for tackling net zero. Borrowing costs remain extremely low even if they are starting to rise. The UK continues to be one of the most prosperous countries in the world. And relatively small changes can have a big impact over a 25 to 50-year timeframe.

Getting the public finances back under control will not be easy. But it can be done.

Alison Ring OBE FCA, Director of Public Sector and Taxation at ICAEW, commented: “The challenges facing the public finances are immense and I don’t envy Rishi Sunak the difficult choices he has to make in balancing the demands on the public purse with the real-world impact of decisions to increase, maintain or cut spending across both central and local government.

“Much of the focus on the Spending Review and Autumn Budget will be on how the Chancellor plans to tackle the immediate challenges facing the country this winter and how he plans to balance competing demands over the three years of the Spending Review. However, setting out a fiscal strategy to address long-term fiscal pressures and put the public finances on a sustainable path will be even more important.”

Martin Wheatcroft FCA, external advisor on public finances to ICAEW, added: “There are signs that the government is starting to think more strategically about the public finances, such as in starting to plan for the tax consequences of decarbonisation, identifying the major pressures on public spending that flow from more people living longer, and biting the bullet by increasing taxes to fund those pressures.

“The Spending Review and Autumn Budget on 27 October provide an opportunity for the government to develop that thinking further and to set out an approach that looks beyond the current parliamentary cycle to strengthening the capacity and resilience of the public finances over the longer term.”