We take a look at what makes up UK public debt and who it is owed to, before the Chancellor borrows hundreds of billions more in his emergency fiscal event.

We take a look at what makes up UK public debt and who it is owed to, before the Chancellor borrows hundreds of billions more in his emergency fiscal event.

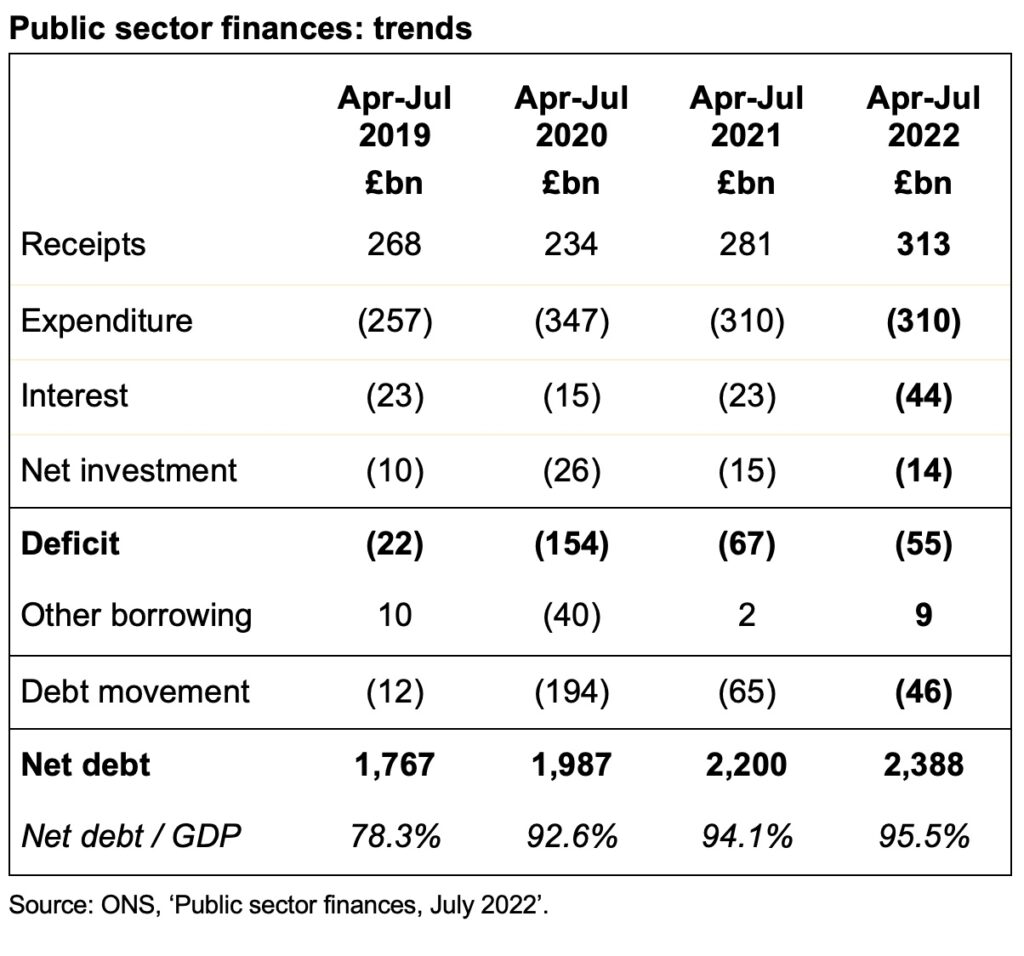

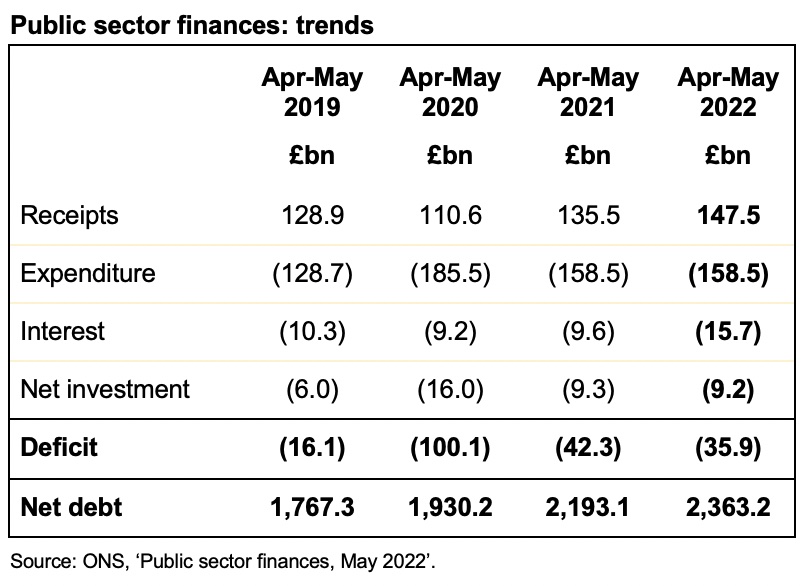

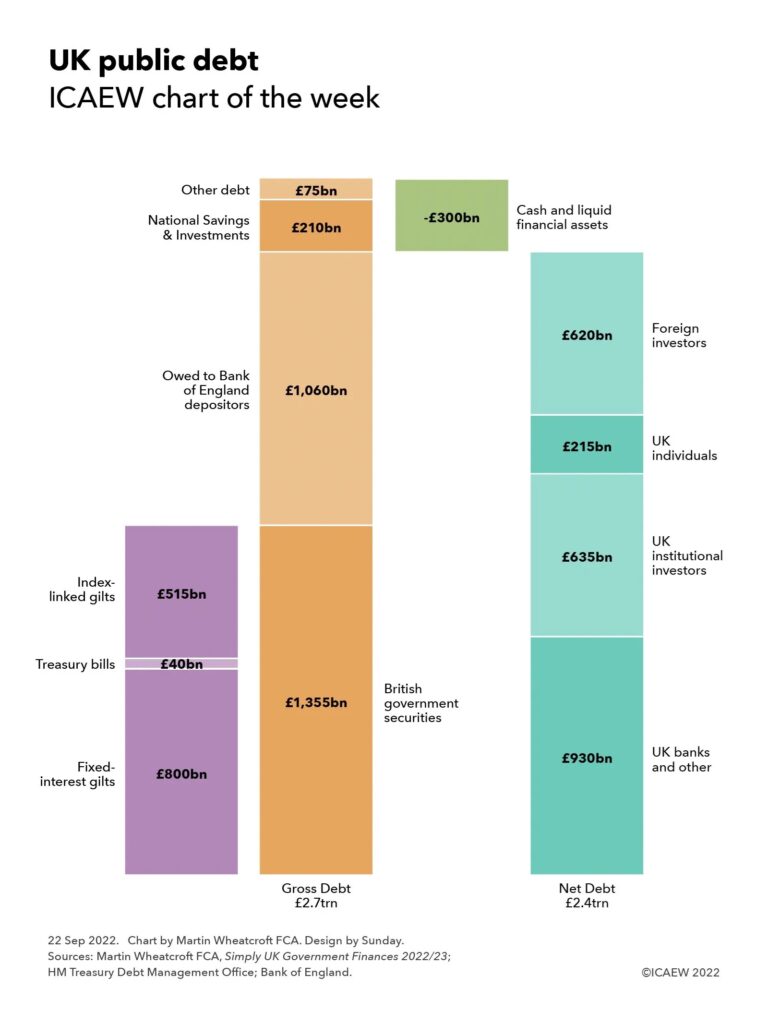

Our chart this week is on public debt, illustrating how public sector gross debt is currently in the region of £2.7tn and public sector net debt is in the order of £2.4trn.

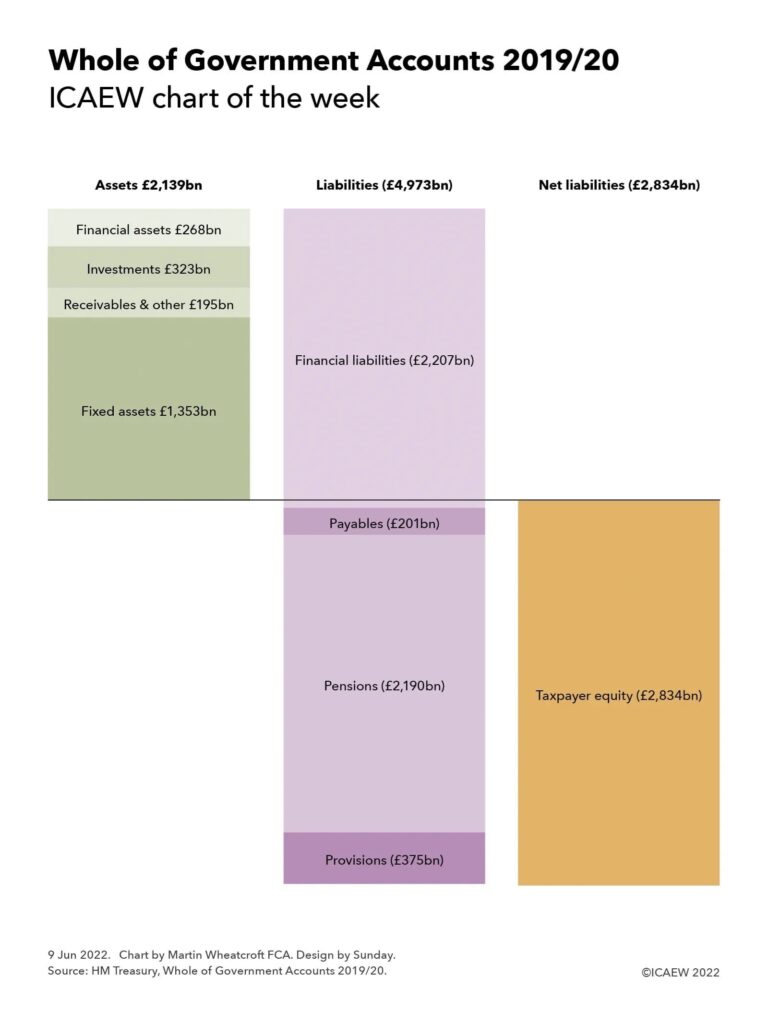

HM Treasury owes £2.1trn to holders of British government securities, of which approximately £745bn is owed to the Bank of England and £1,355bn to external investors. These securities are tradable on the London Stock Exchange, comprising fixed-interest bonds (‘gilts’) with an average maturity of 14 years, retail price index-linked gilts with an average maturity of 18 years and treasury bills that mature and roll over within six months or less.

The next largest public sector borrower is the Bank of England, which owes around £1,060bn to its depositors. This mostly comprises deposits created under its quantitative easing programme to support the economy, in the order of £850bn to finance fixed-interest gilt purchases, £20bn to finance corporate bond purchases and around £190bn to finance Term Funding Scheme loans.

The public is directly owed £210bn in the form of National Savings & Investments premium bonds and savings certificates.

The balance of £75bn comprises £25bn in Network Rail loans, £15bn in local authority external debt (local authorities owe £120bn in total, but £105bn is owed to central government) and £35bn in other sterling and foreign currency debt. These numbers do not include £21bn in central government leases and £10bn in other debts that have recently been added to the official measure for government debt following changes in methodology.

After deducting £300bn in cash and other liquid assets, this means public sector net debt stands at around £2.4trn, of which in the order of £930bn is owed to UK banks and other financial institutions, £635bn to UK institutional investors (pension funds and insurance companies), £215bn to UK individual investors, and £620bn to foreign investors, including foreign central banks and governments as well as private sector investors.

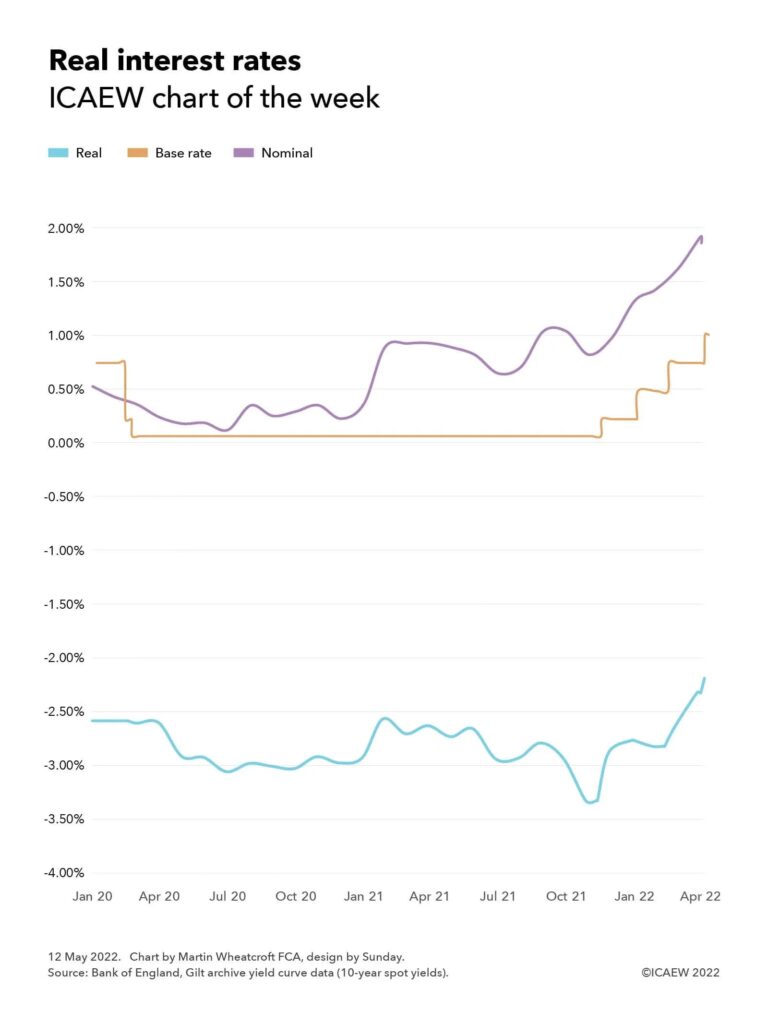

The chart illustrates how, despite the efforts of HM Treasury’s Debt Management Office to lock in fixed interest rates for long periods, the government is exposed to significant interest rate and inflation exposure, with the Bank of England having – in effect – swapped a significant proportion of government debt from fixed-rate gilts into variable rate central bank deposits through its quantitative easing programmes.

The consequence is that the majority of public debt is exposed to changes in interest rates or, in the case of index-linked gilts, to changes in retail price inflation, driving interest costs higher and higher each time the Bank of England raises its benchmark central bank deposit rate.

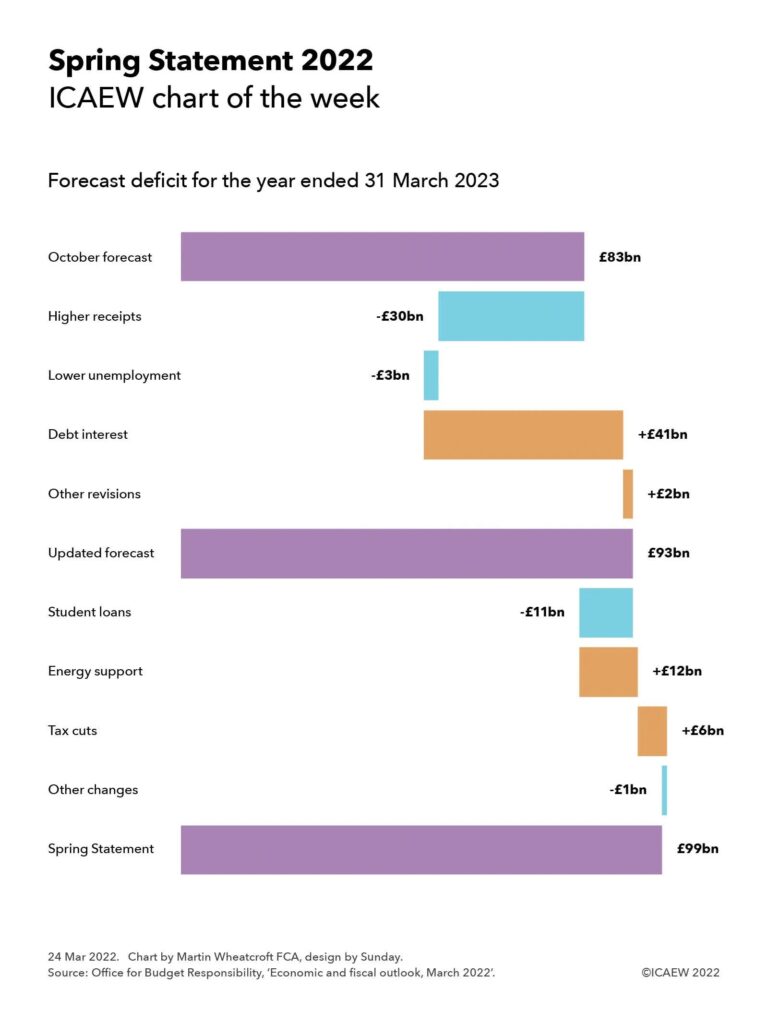

This provides a difficult backdrop for the Chancellor’s plans to borrow substantial sums to cut taxes, cap energy prices for households and businesses and increase defence spending. Most of the extra borrowing will be financed by issuing new British government securities at a time when the Bank of England is starting to put its quantitative easing programme into reverse and so selling some of its stock of fixed-interest gilts back into the market.

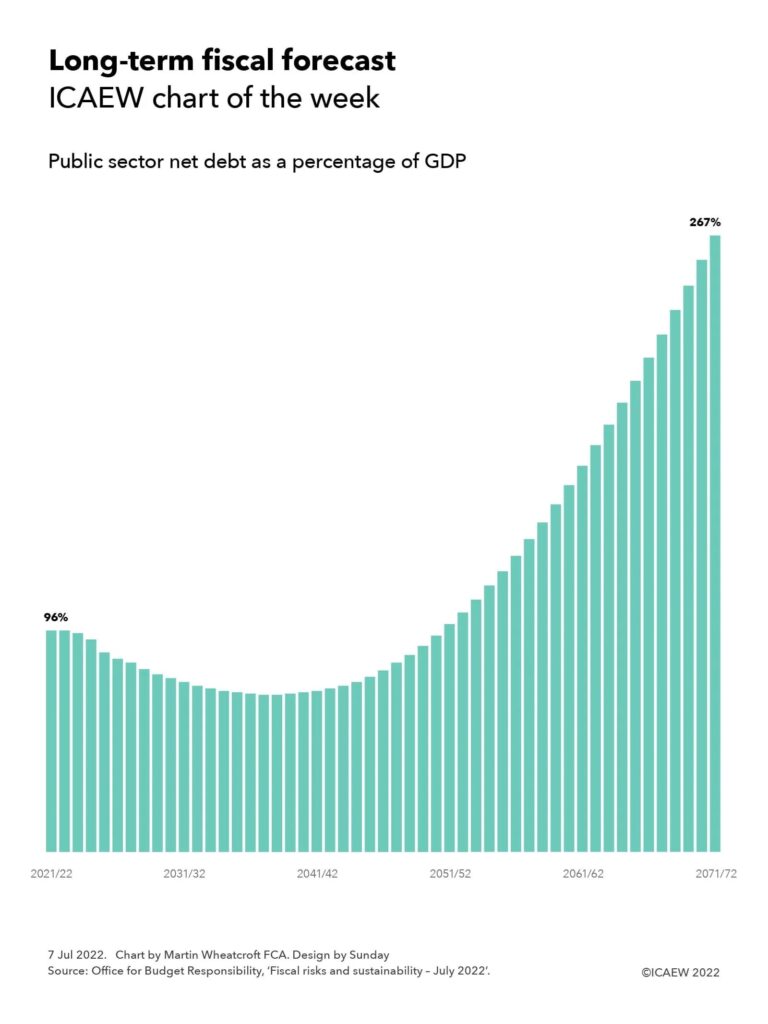

There is no need for an official forecast to be confident of two things: public debt, and the cost of public debt, are both going up.