Given that capital budgets are often the first to be cut when money is tight, will the planned growth in capital investment survive the Spending Review later this month?

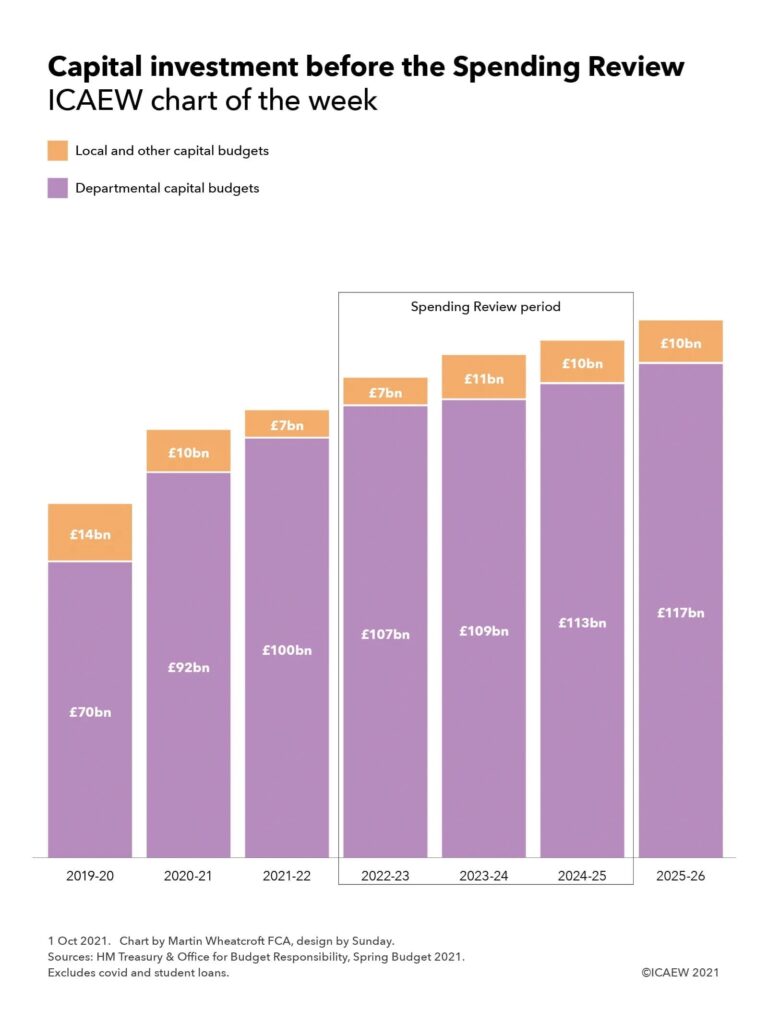

Our chart this week is on public sector capital investment, illustrating how central department capital budgets increased from £70bn two years ago to £92bn last year and £100bn this year, with further increases planned up to £117bn in 2025-26. This path was originally set by former Chancellor Philip Hammond who believed boosting capital investment, particularly on infrastructure, would help address the productivity gap that has constrained economic growth over the last decade. Chancellor Rishi Sunak has broadly adopted the same approach of increasing capital budgets in the first half of the 2020s, but with the rather snappier objective of ‘levelling up’ opportunity across the country.

Local and other capital budgets in the public sector are actually significantly higher than those shown in the chart (£14bn, £10bn, £7bn, £7bn, £11bn, £10bn and £10bn in 2019-20 through 2025-26), but that is primarily because a substantial proportion of both local government and public corporation capital investment is funded through central government capital grants, which are already included within departmental capital budgets. The balance, funded by local taxation and non-tax revenues, has actually fallen in the last few years, especially as many local authorities have tightened their belts as social care and other costs have outstripped council tax receipts.

The Treasury announced last month that the envelope for the Spending Review would adopt the capital spending profile already set out in the Spring Budget in March as shown in our chart, with core capital department expenditure limits (Core CDEL) of £107bn in 2022-23, £109bn in 2023-24 and £113bn in 2024-25. It seems likely that the government will stick ahead with these capital plans, unlike the profile for departmental current spending (Core resource department expenditure limits or Core RDEL, not shown in the chart) which increased by £15bn, 12bn and £14bn respectively to £408bn in 2022-23, £422bn in 2023-24 and £441bn in 2024-25 to address the increasing demands being placed on health care as more people live longer and to address the social care crisis.

While this extra current spending is to be funded by the new health and social care levy, there remain huge pressures on many other public services as well as concerns about the risks to tax receipts from an uncertain economic recovery. The temptation to raid capital budgets to top up current spending, as occurred in the years following the financial crisis, will be there. After all, the benefits of capital investment can often take many years to arrive, while the stresses experienced by public services are much more immediate. In addition, under government fiscal rules, capital expenditure counts towards reported expenditure (total managed expenditure or TME) and the public sector deficit, which perhaps makes it more difficult to treat investment for the long-term differently from day-to-day operating expenditure.

Assuming the Chancellor sticks to the plan, then the big story of the Spending Review from a capital expenditure perspective will be in the allocation between departments. Transport (£18bn in 2021-22), Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (£16bn) and Defence & Intelligence (£15bn) are the largest spenders, and each will be fighting hard for more money, especially Defence where governmental ambitions to be a ‘tier 1’ military power have always outstripped the amount of money supplied. Other departments likely to be seeking additional capital funding include the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities on behalf of local authorities in England (£9bn in 2021-22) and the devolved administrations (together £9bn).

Will the Chancellor be able to steer a course through what appear to be some turbulent economic waters to deliver on the government’s infrastructure ambitions?