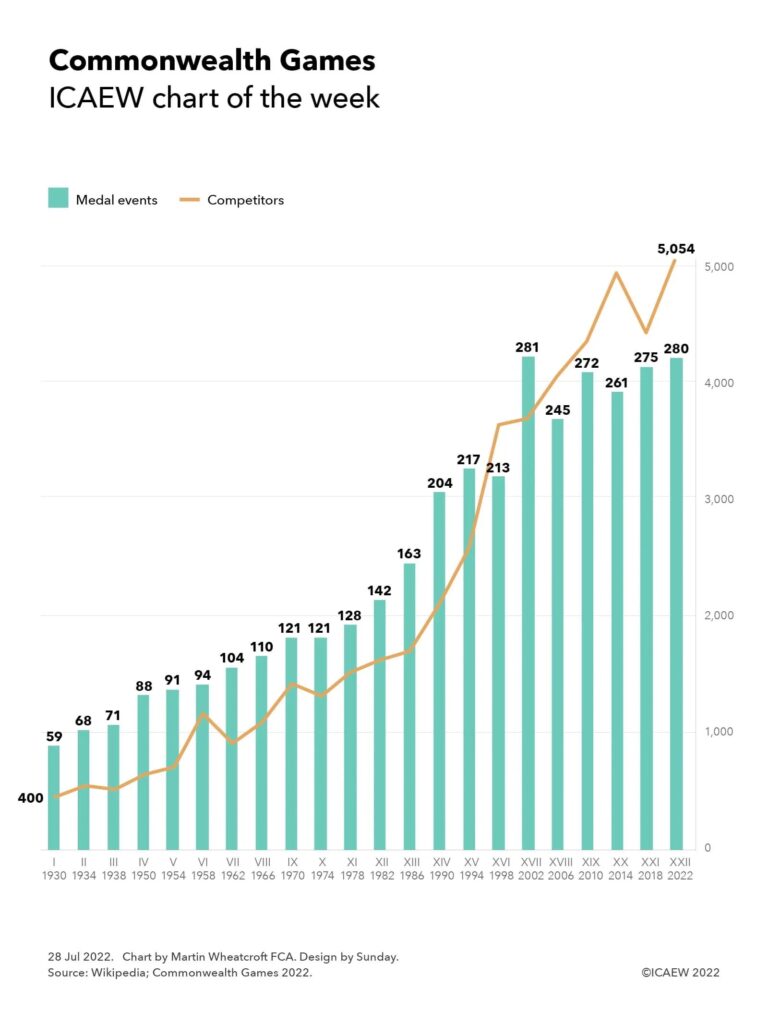

Our chart this week marks the start of the XXII Commonwealth Games in Birmingham, illustrating how the numbers of events and competitors have grown since the first games in 1930 to reach 280 events featuring 5,054 competitors in 2022.

The XXII Commonwealth Games in Birmingham, from 28 July to 8 August, involves a record 5,054 competitors from 72 teams participating in 280 events in 20 sports. This is many times the 400 or so competitors from 11 teams that competed in 59 events in six sports at the inaugural British Empire Games in Hamilton, Canada, in 1930.

Although much smaller than the Olympic Games, the Commonwealth Games is still a major undertaking with a budget for Birmingham 2022 approaching a billion pounds, including £778m of public funding, of which £594m is from central government and £184m is from Birmingham City Council, West Midlands city region and other local sources.

The main focus will be on sporting performance, with events in aquatics (12 diving, 52 swimming), athletics (58), badminton (6), 3×3 basketball (4), beach volleyball (2), boxing (16), cricket T20 (1), cycling (20 track, 4 road, 2 mountain biking), gymnastics (14 artistic, 6 rhythmic), hockey (2), judo (14), lawn bowls (11), netball (1), para powerlifting (4), rugby sevens (2), squash (5), table tennis (11), triathlon (5), weightlifting (16) and wrestling (12).

Birmingham 2022 is the first games to have more than 5,000 competitors, although with 280 medal events there is one less than the 281 that featured in Manchester 2002.

England, as the host nation, will be hoping to improve on its performance at the Gold Coast 2018 games, when it came second in the medal table with 136 medals (45 gold, 45 silver, 46 bronze) to Australia, who won 198 medals (80, 59, 59) on their home turf. India with 66 medals in 2018 (26, 20, 20), Canada with 82 (15, 40, 27), New Zealand with 46 (15, 16, 15), South Africa with 37 (13, 11, 13), Wales with 36 (10, 12, 14) and Scotland with 44 (9, 13, 22) will also be looking to do well.

For the participants, the efforts will be intense, while for spectators in the stadium and the audience at home, the nail-biting tension of the lawn bowls competition will be just one of many gripping sporting events to be enjoyed this summer.