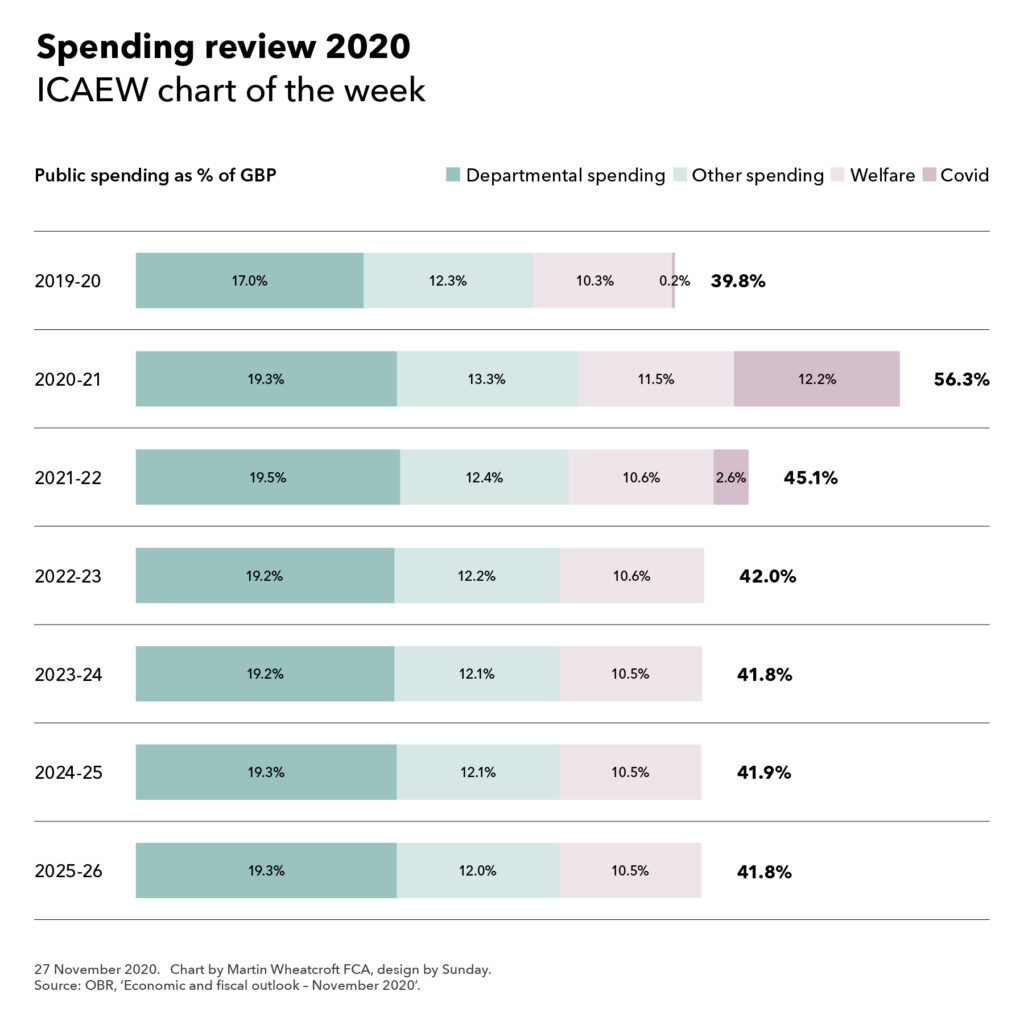

5 February 2021: This week’s chart focuses on the Japanese economy as it seeks to return to relative fiscal normality in the year commencing 1 April 2021, following multiple supplementary budgets in its current financial year.

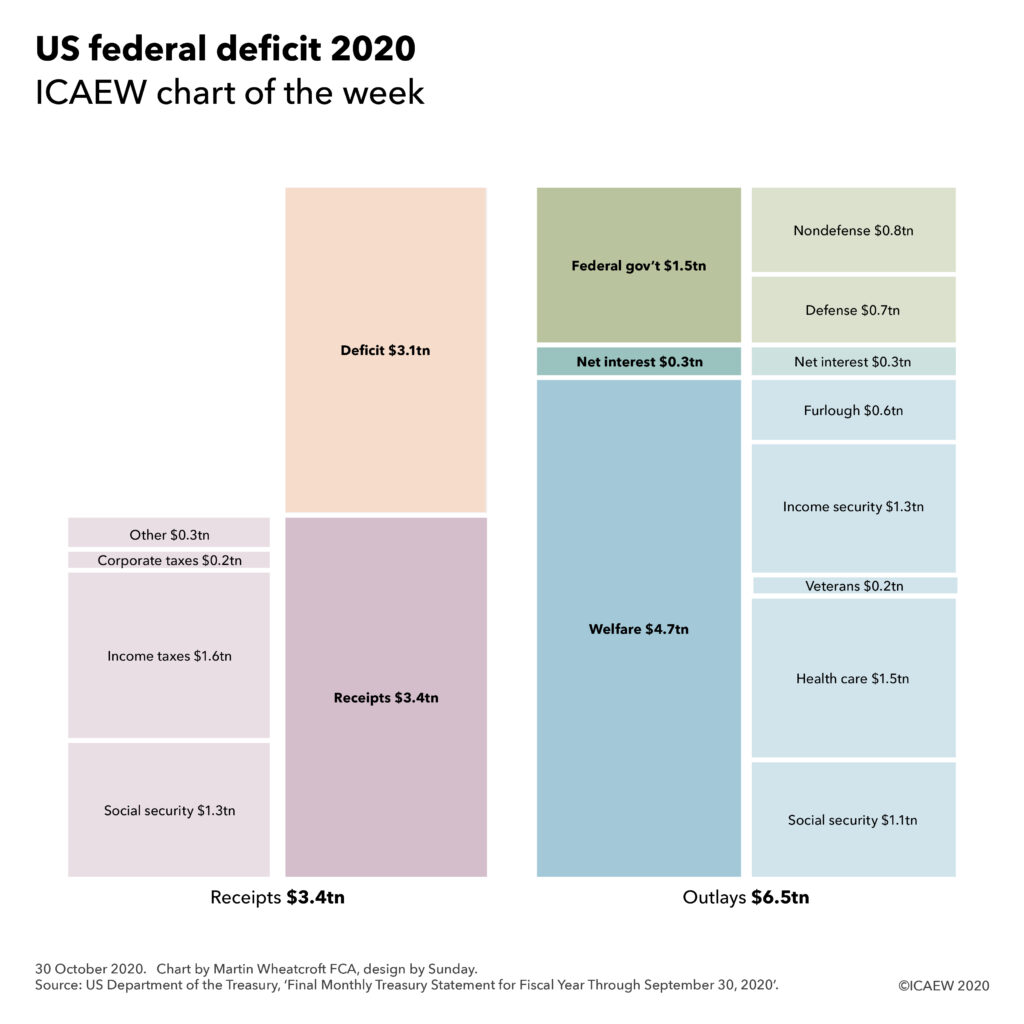

The #icaewchartoftheweek is full of anticipation for the UK Budget next month and so decided to take a look at how the Japanese central government plans to borrow ¥28.9tn (£205bn) in the year to 31 March 2022. Together with taxes and other income of ¥63.0tn (£450bn), this will be used to fund ¥86.9tn (£620bn) of spending and a ¥5.0tn (£35bn) COVID-19 contingency.

This follows a significant amount of borrowing in the current financial year, with the 2020-21 Budget amended by three supplementary Budgets in response to the coronavirus pandemic. If temporary and special measures are excluded, the 2021-22 Budget reflects a 0.7% increase in spending over the previous year’s ¥86.3tn (£615bn) pre-COVID budget.

Spending comprises ¥35.8tn (£255bn) on social security, central government spending of ¥26.1tn (£185bn), and other spending of ¥16.5tn (£120bn), with the latter principally relating to transfers and grants to local government. Interest of ¥8.5tn (£60bn) is only marginally higher than the previous year’s ¥8.3tn, despite a 9% increase in the level of government bonds outstanding to ¥990tn (£7tn) – equivalent to 177% of GDP – at March 2022.

Borrowing has increased over pre-pandemic levels, with net borrowing of ¥28.9tn (£205bn) in 2021-22 compared with the 2020-21 pre-pandemic budget of ¥18.0tn (£130bn, not shown in the chart). This is principally driven by a 10% decline in anticipated income, with taxes and other income of ¥63.0tn (£450bn) falling from the ¥70.1tn (£500bn) originally budgeted for the current year (but not actually received).

The chart does not include the substantial amounts of taxation raised and spent by its 47 regional prefectures and so does not provide a complete fiscal picture for Japan. However, it does provide an indication of how the Japanese public finances have been able to respond to the pandemic.

The Japanese government will be hoping that there will be no need for supplementary Budgets in the coming financial year, as no doubt will UK Chancellor Rishi Sunak as he prepares for his government’s Budget on 3 March.