Boost from self assessment tax receipts not enough to prevent a deficit in July as Chancellor searches for cost savings in the run up to the Autumn Budget.

The monthly public sector finances for July 2024 released by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) on Wednesday reported a provisional deficit for the first four months of the 2024/25 financial year of £51.4bn, £4.7bn worse than budgeted.

Alison Ring OBE FCA, ICAEW Director of Public Sector and Taxation, says: “Today’s data shows that the customary boost from self assessed tax receipts in July was not enough to prevent a deficit of £3.1bn, higher than budgeted, as cost pressures drove up public spending. Debt increased to £2,746bn or 99.4% of GDP at the end of July, up £5.9bn from the end of June 2024.

“The government is now in crisis control mode as it searches for savings to offset significant unbudgeted cost overruns in this financial year, with the cumulative deficit to July 2024 standing at £51.4bn, £4.7bn more than budgeted.

“Rumours that the government is looking at significant cuts in public investment programmes this year to keep within budget are concerning, given the importance to economic growth of infrastructure and the urgent need for upfront investment in technology to fix poorly performing public services. Our hope is that the Chancellor will be able to take a more strategic view in her Autumn Budget in October and in the Spending Review in the spring.”

Month of July 2024

There was a shortfall between receipts and spending of £3.1bn in the month of July 2024, £1.8bn higher than in July 2023 and £3.0bn worse than the budgeted deficit of £0.1bn.

Taxes and other receipts amounted to £99.4bn in July 2024, up £10.3bn or 12% from the previous month driven by self assessment income tax receipts in July, in line with the trend last year. Receipts were £2.0bn or 2% higher than in the same month last year, in contrast with total managed expenditure of £102.5bn, which was £3.8bn or 4% higher than in July 2023.

Financial year to date

The shortfall between receipts and spending of £51.4bn for the four months to July 2024 was £0.5bn better than in the same period last year, but £4.7bn over budget.

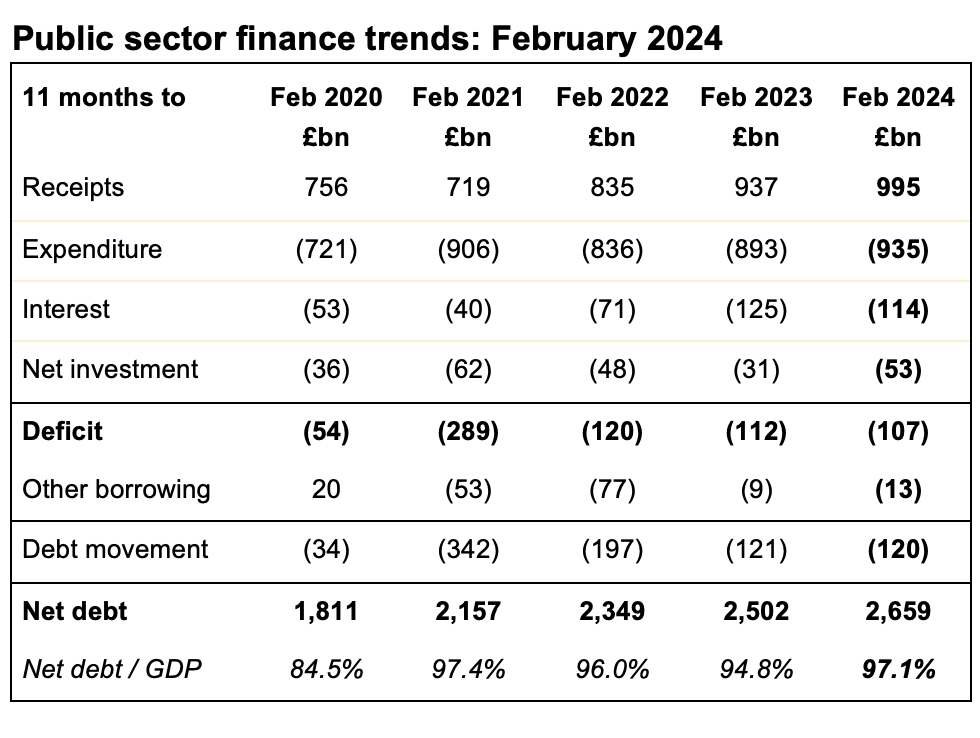

Cumulative taxes and other receipts amounted to £359.3bn in the first third of the financial year, up 2% compared with the same period last year, while total managed expenditure was 2% higher at £410.7bn. This is illustrated by Table 1, which highlights how cuts to employee national insurance rates have been offset by higher income tax, VAT, corporation tax, and non-tax receipts.

Total managed expenditure for the first four months of £410.7bn was also up by 2% compared with April to July 2023, but this reflected spending on public services up 4%, welfare spending up 6% and gross investment up 10% driven by overruns and construction cost inflation being offset by lower energy-support subsidies and lower debt interest.

The reduction in debt interest of £6.1bn compared with the first four months of last year was driven by a £26.5bn swing in indexation on inflation-linked debt that more than offset a £20.4bn increase in interest on variable and fixed-rate debt.

Table 1: Summary receipts and spending

| Apr-Jul 2024 £bn | Apr-Jul 2023 £bn | Change % | |

| Income tax | 89.9 | 86.4 | +4% |

| VAT | 67.9 | 66.0 | +3% |

| National insurance | 53.5 | 58.3 | -8% |

| Corporation tax | 34.0 | 31.6 | +8% |

| Other taxes | 73.5 | 72.1 | +2% |

| Other receipts | 40.5 | 37.5 | +8% |

| Total receipts | 359.3 | 351.9 | +2% |

| Public services | (212.2) | (204.8) | +4% |

| Welfare | (103.1) | (97.5) | +6% |

| Subsidies | (10.6) | (14.0) | -24% |

| Debt interest | (46.6) | (52.7) | -12% |

| Gross investment | (38.2) | (34.8) | +10% |

| Total spending | (410.7) | (403.8) | +2% |

| Deficit | (51.4) | (51.9) | -1% |

Table 2 summarises how public sector net borrowing (PSNB) to fund the deficit of £51.4bn combined with borrowing of £4.4bn to fund working capital movements, student loans and other financing requirements increased debt by £55.8bn during the first four months of the financial year. As a result, public sector net debt grew to £2,745.9bn on 31 July 2024, which is £931bn or 51% more than the £1,815bn reported for 31 March 2020 at the start of the pandemic.

The ratio of net debt to GDP ratio is at the highest it has been since the 1960s, having increased by 1.3 percentage points from 98.1% on 1 April 2024 to 99.4% on 31 July 2024. Borrowing to fund the deficit was equivalent to 1.9% of GDP and other borrowing was equivalent to 0.2%, an increase of 2.1% before being offset by 0.8% from the effect of inflation and economic growth on GDP (usually referred to as ‘inflating away’). Lower inflation this year means this effect is less pronounced than in the same period last year.

Table 2: Public sector net debt and net debt/GDP

| Apr-Jul 2024 £bn | Apr-Jul 2023 £bn | |

| PSNB | 51.4 | 52.3 |

| Other borrowing | 4.4 | (11.4) |

| Net change | 55.8 | 40.9 |

| Opening net debt | 2,694.1 | 2,539.7 |

| Closing net debt | 2,745.9 | 2,580.6 |

| PSNB/GDP | 1.9% | 2.0% |

| Other/GDP | 0.2% | (0.4%) |

| Inflating away | (0.8%) | (1.5%) |

| Net change | 1.3% | 0.1% |

| Opening net debt | 98.1% | 95.7% |

| Closing net debt | 99.4% | 95.6% |

Public sector net worth, the new balance sheet metric launched by the ONS last year, was -£740bn on 31 May 2024, comprising £1,613bn in non-financial assets and £1,062bn in non-liquid financial assets minus £2,746bn of net debt (£343bn liquid financial assets – £3,089bn public sector gross debt) and other liabilities of £669bn. This is a £67bn deterioration from the start of the financial year and is £123bn more negative than in July 2023.

Revisions and other matters

Caution is needed with respect to the numbers published by the ONS, which are expected to be repeatedly revised as estimates are refined and gaps in the underlying data are filled. This includes local government, where monthly data is based on budget or high level estimates in the absence of monthly data collection.

The latest release saw the ONS reduce the reported deficit for the first three months of the financial year by £1.5bn from £49.8bn to £48.3bn as estimates were revised for new data.