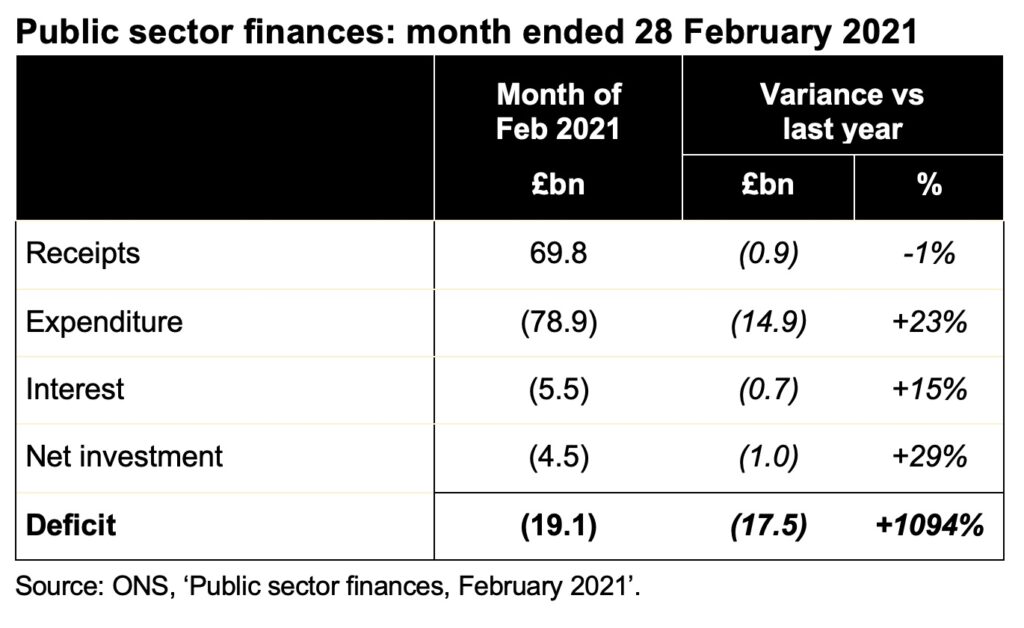

The UK reported a £28.0bn fiscal deficit in March 2021, bringing the total shortfall for 2020-21 to £303.1bn. The last month of the financial year saw net investment of £10.3bn, up from a monthly average of £4.0bn over the previous eleven months.

The latest public sector finances released on Friday 23 April reported a deficit of £28.0bn for March 2021, as COVID-related spending continued to weigh on the public finances. This brought the cumulative deficit for the financial year to £303.1bn, £246.0bn more than the £57.1bn reported for the same period last year.

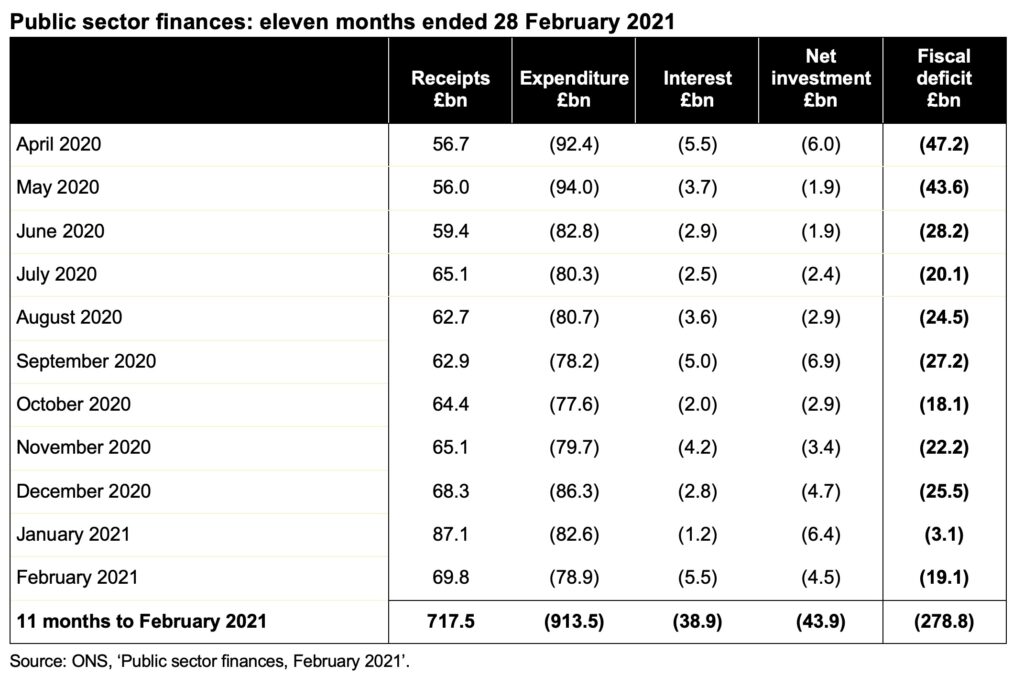

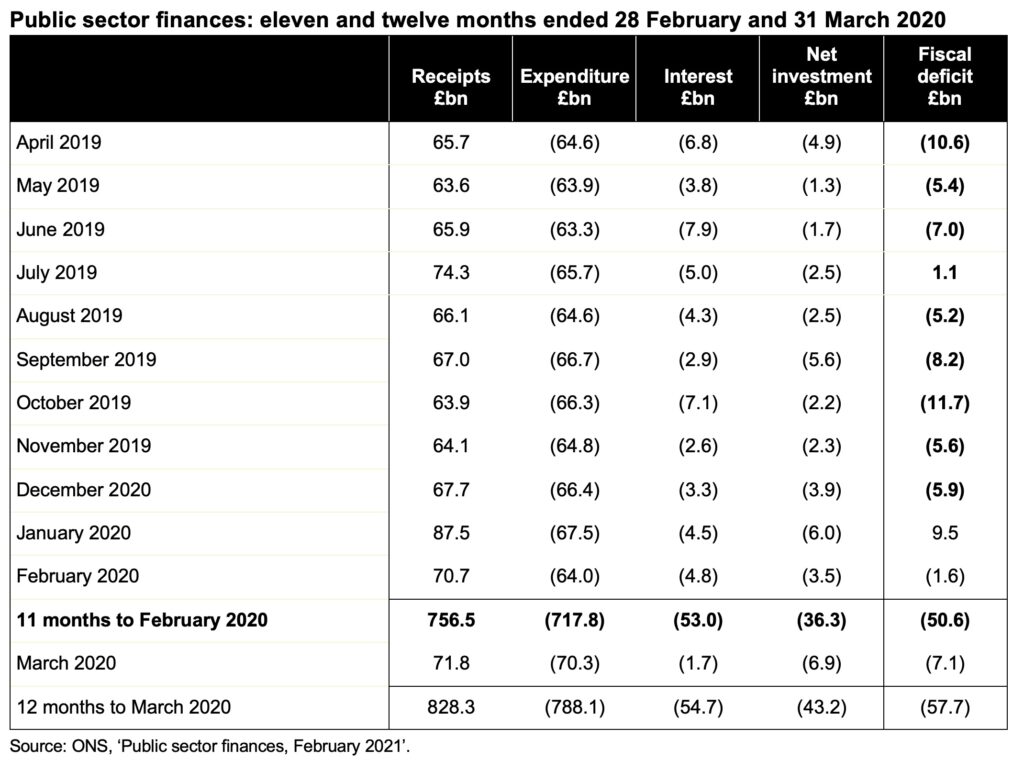

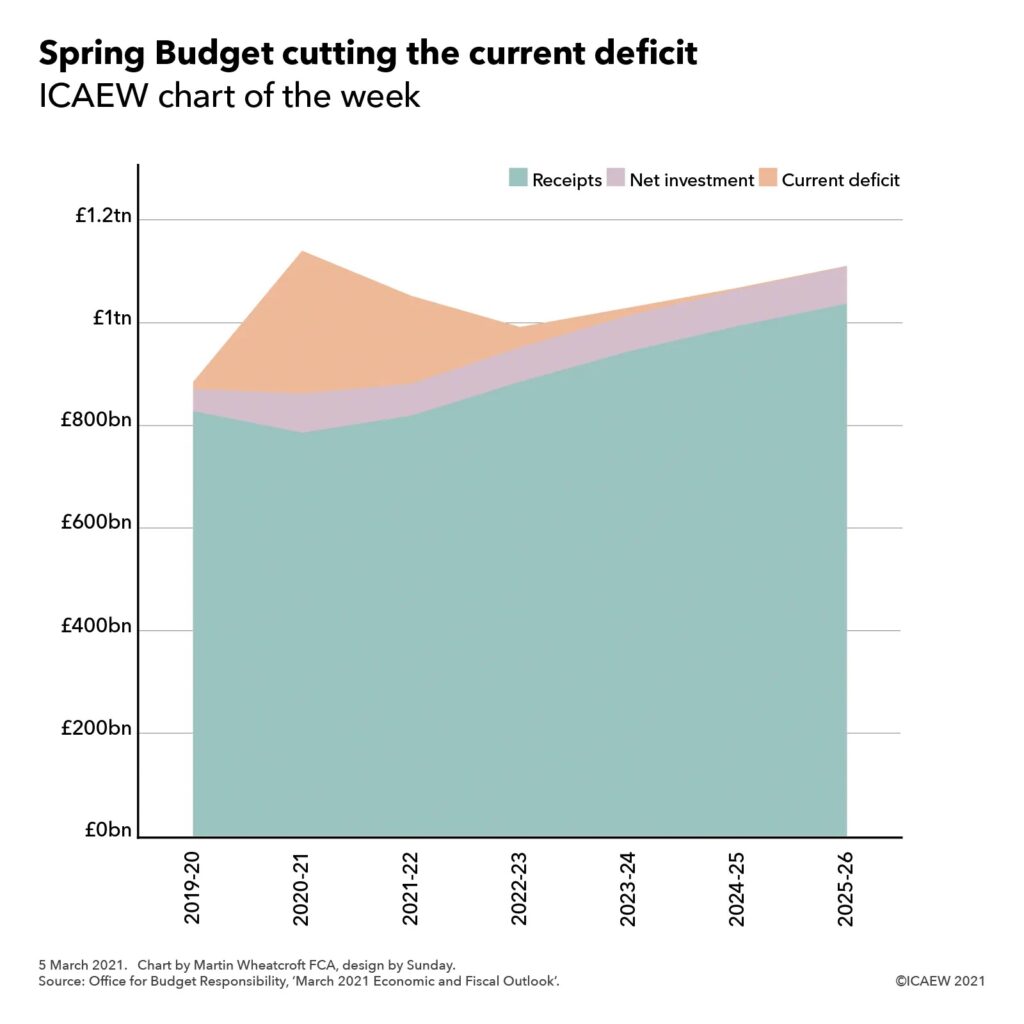

The combination of receipts down 5%, expenditure up 27% and net investment up 25% has resulted in a deficit for the twelve months to March 2021 that is more than five times as much as the budgeted deficit of £55bn for the whole of the 2020-21 financial year set in the Spring Budget in March, despite interest charges being lower by 25%.

The deficit is smaller than the £354.6bn forecast by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) in March as the economy has been less damaged than was feared, despite the extended lockdown during the final quarter of the financial year. However, some of this difference relates to spending that has been deferred into the following financial year, while the provisional numbers also exclude £27bn of bad debts on COVID-related lending that were included in the OBR forecast.

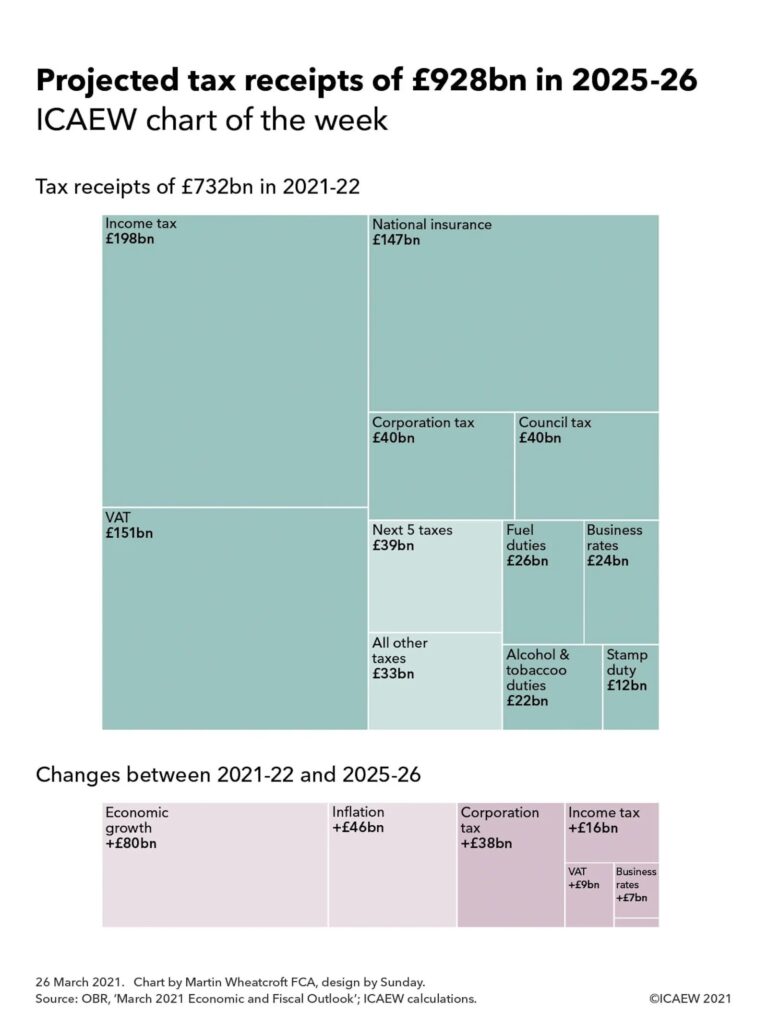

Falls in VAT, corporation tax and income tax receipts and the waiver of business rates were the principal driver of lower tax revenues over the last twelve months, while large-scale fiscal interventions have resulted in much higher levels of expenditure.

Net investment is greater than last year (mostly as planned), while the interest expense line has benefited from ultra-low interest rates. March 2021 saw a return to the traditional end-of-financial-year rush to get capital budgets spent, with net investment spending of £10.3bn in March contrasting with an average of £4.0bn over the previous eleven months.

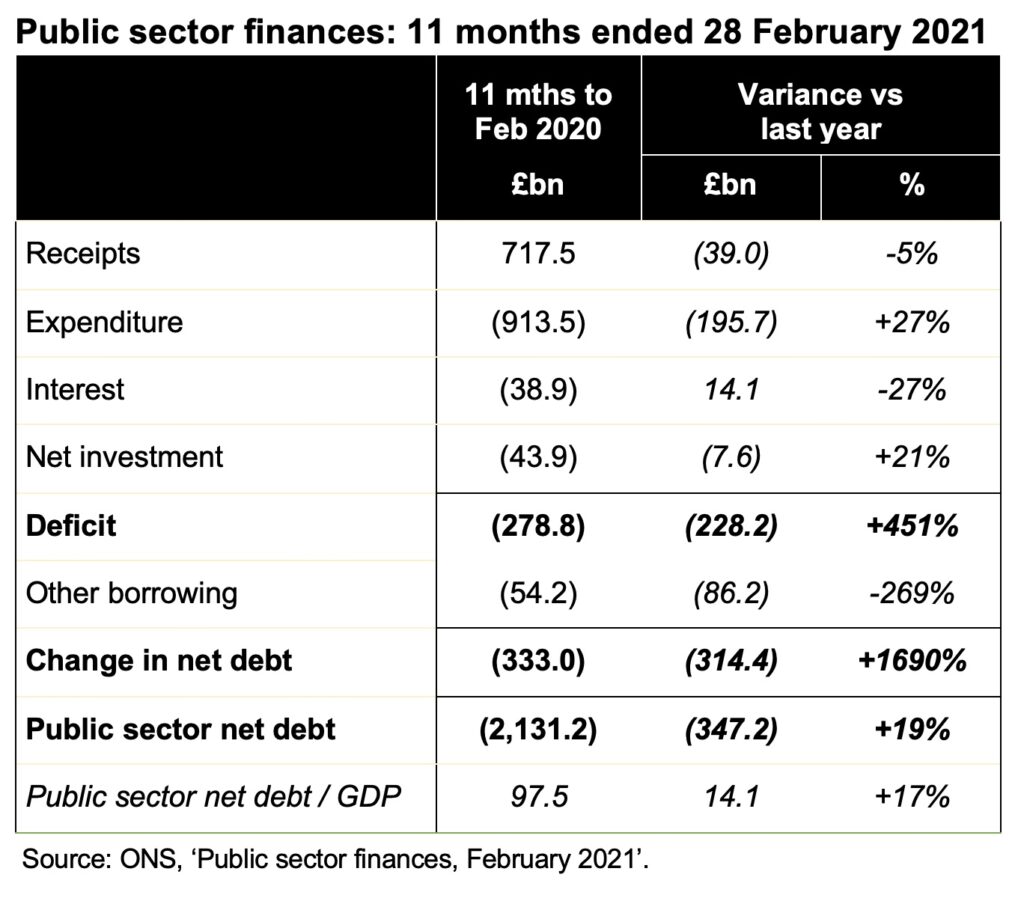

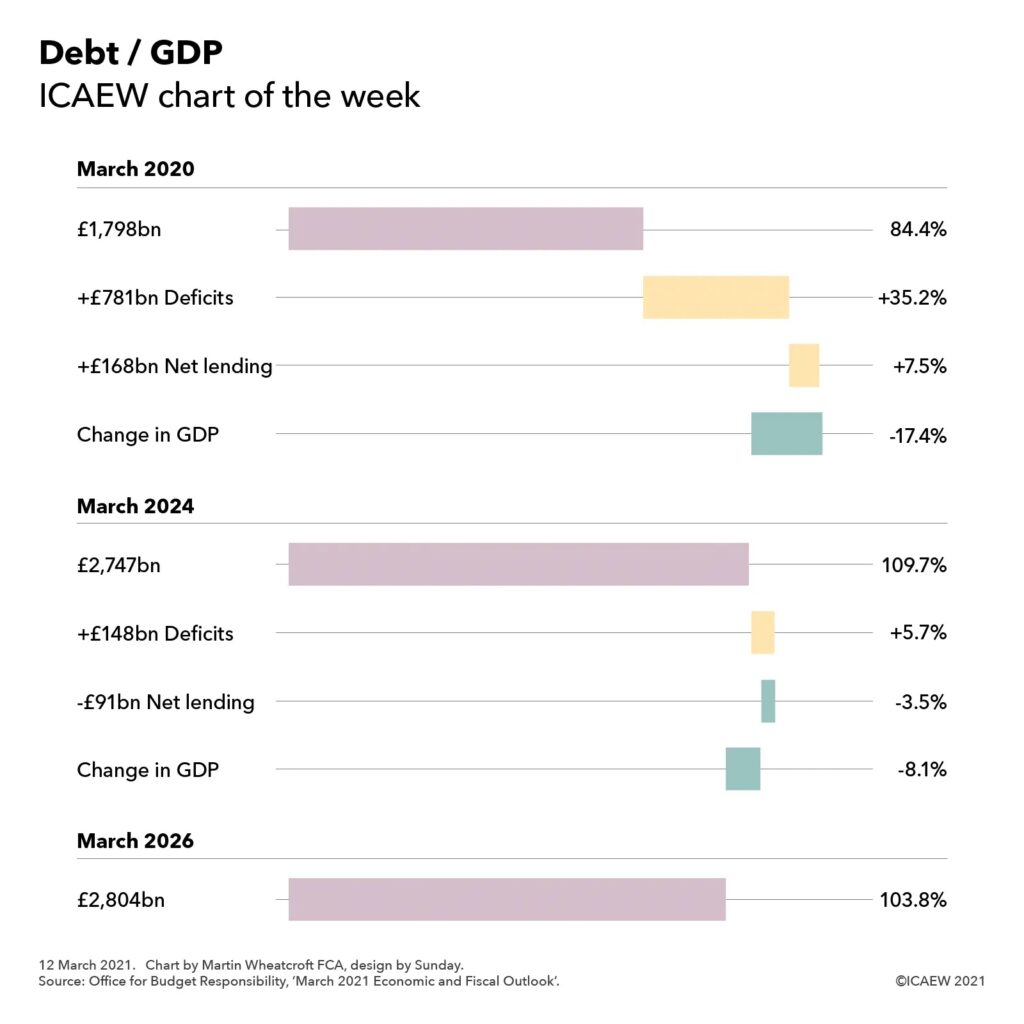

Public sector net debt increased to £2,141.7bn or 97.7% of GDP, an increase of £344.0bn from the start of the financial year. This reflected £40.9bn of additional borrowing over and above the deficit, much of which has been used to fund coronavirus loans to businesses and tax deferral measures. Although net debt was reported as exceeding 100% of GDP at various points during the financial year, slightly improved GDP numbers have kept the ratio below that point.

The cash outflow (the ‘public sector net cash requirement’) for the month was £16.4bn, increasing the cumulative total cash outflow for 2020-21 to £339.0bn. This is a significant increase over the cumulative net cash outflow of £17.2bn reported for 2019-20.

Caution is needed with respect to the numbers published by the ONS, which are expected to be repeatedly revised as estimates are refined and gaps in the underlying data are filled.

The ONS made a number of revisions to prior month and prior year fiscal numbers to reflect revisions to estimates and changes in methodology. These had the effect of reducing the reported fiscal deficit in the first eleven months from £278.8bn to £275.1bn and the reported deficit for 2019-20 from £57.7bn to £57.1bn.