My chart for ICAEW this week shows how the high level of public debt is the main factor shaping next week’s Autumn Budget.

In the run up to next week’s Autumn Budget it has become clear that the Chancellor has very little room for manoeuvre.

In past fiscal events, a moderate downgrade in the economic and fiscal forecasts (see last week’s chart of the week) would typically be dealt with by allowing borrowing to rise, albeit in combination with a small cut in planned public spending (often to capital expenditure) and perhaps some minor tax rises.

This time is different. Borrowing – the normal safety valve for adverse forecast changes – is constrained by the existing high level of debt and by government’s existing plan to borrow substantial sums over the next five years, as illustrated by our chart of the week.

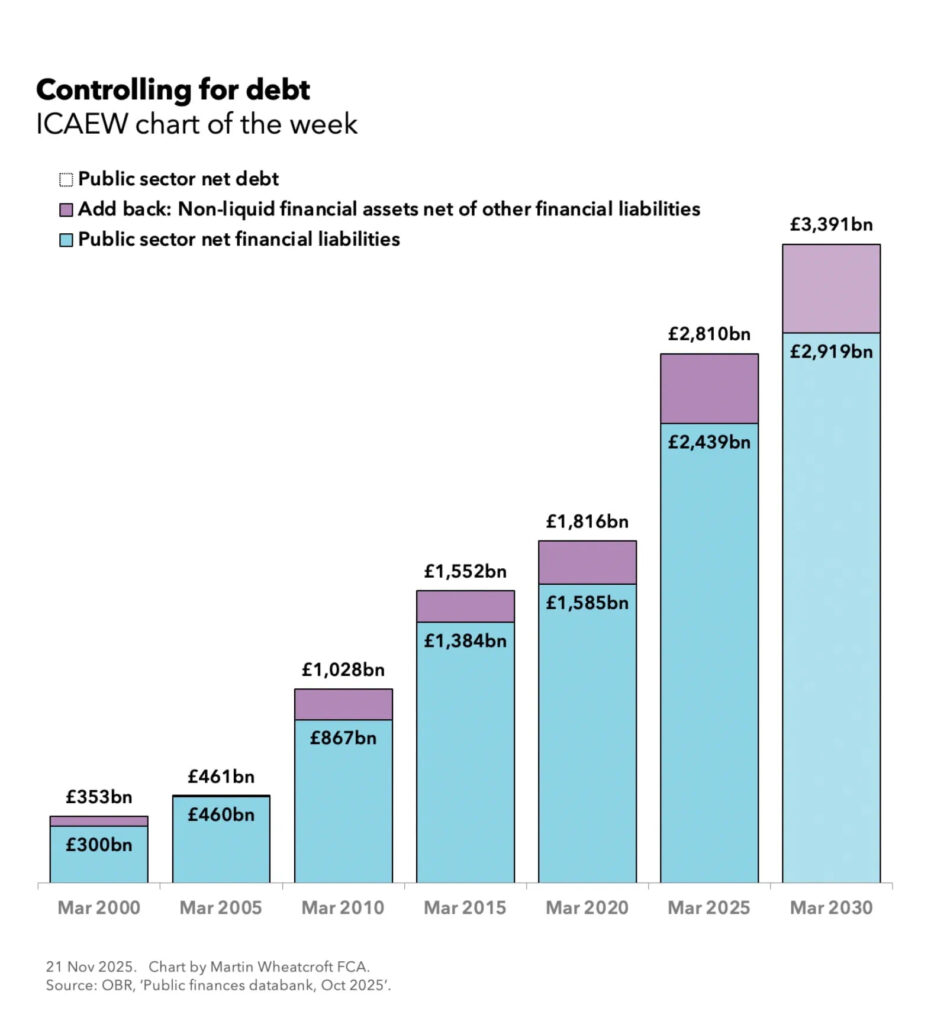

As my chart for ICAEW sets out, public sector net debt has risen over the past quarter of a century from £353bn on 31 March 2000 to £461bn in 2005, £1,028bn in 2010, £1,552bn in 2015, £1,816bn in 2020 and £2,810bn in 2025. It is forecast to rise further to £3,391bn on 31 March 2030.

Although the planned increase of £581bn over the coming five years is less than the £994bn increase over the previous five years, the latter included both the pandemic and an unexpected energy crisis.

The chart also shows how public sector net financial liabilities (PSNFL), the measure of debt that the Chancellor uses for her fiscal rules, increased from £300bn on 31 March 2000 to £2,439bn on 31 March 2025, with a planned rise of £480bn to £2,919bn due to take place on 31 March 2030.

The Chancellor’s debt fiscal rule is for the ratio of PSNFL to GDP starting to fall by 2029/30, or – in other words – for the rate at which debt is increasing to be slower than the rate of growth in the economy in four years’ time. The hope is that the borrowing the government is doing now to invest in infrastructure and economic development will speed up economic growth over that time, but unfortunately that is not yet showing up in the forecasts, which are going in the opposite direction.

With higher borrowing ruled out, the next option would be to look at spending. This also looks difficult as the Spending Review earlier this year locked in departmental budgets for the next few years (to 2028/29 for current spending and to 2029/30 for capital investment). Likewise, significant cuts in welfare spending also appear unlikely given the government’s failure to persuade its MPs to back a plan to cut back on disability and illness benefits and hints that the government wants to lift the two-child benefit cap. The Chancellor could potentially re-open the Spending Review, but that would risk spending going up not down given the continued pressures on health and the criminal justice systems, not to mention the international pressure from President Trump and others to accelerate increases in defence spending.

With other options such as raising the level of net inward migration also ruled out, that leaves taxation as the only real lever available to the Chancellor.

The flood of speculation ahead of next week’s Autumn Budget 2025 has ranged from manifesto-busting increases in one of the ‘big three’ taxes (income tax, VAT and national insurance) and fiscal drag (from the extension of freezes in tax allowances), to a long list of tax raising ideas to bring in just a little bit more money here and there that might together add up to a substantial amount.

At this point it seems that little can be ruled out.