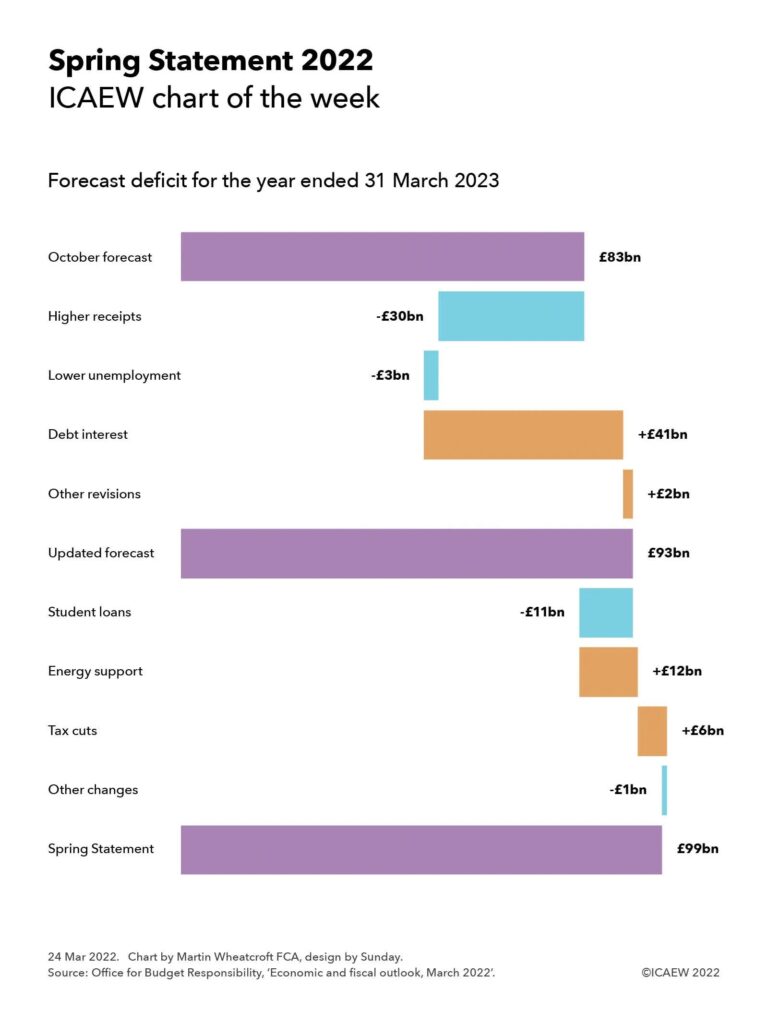

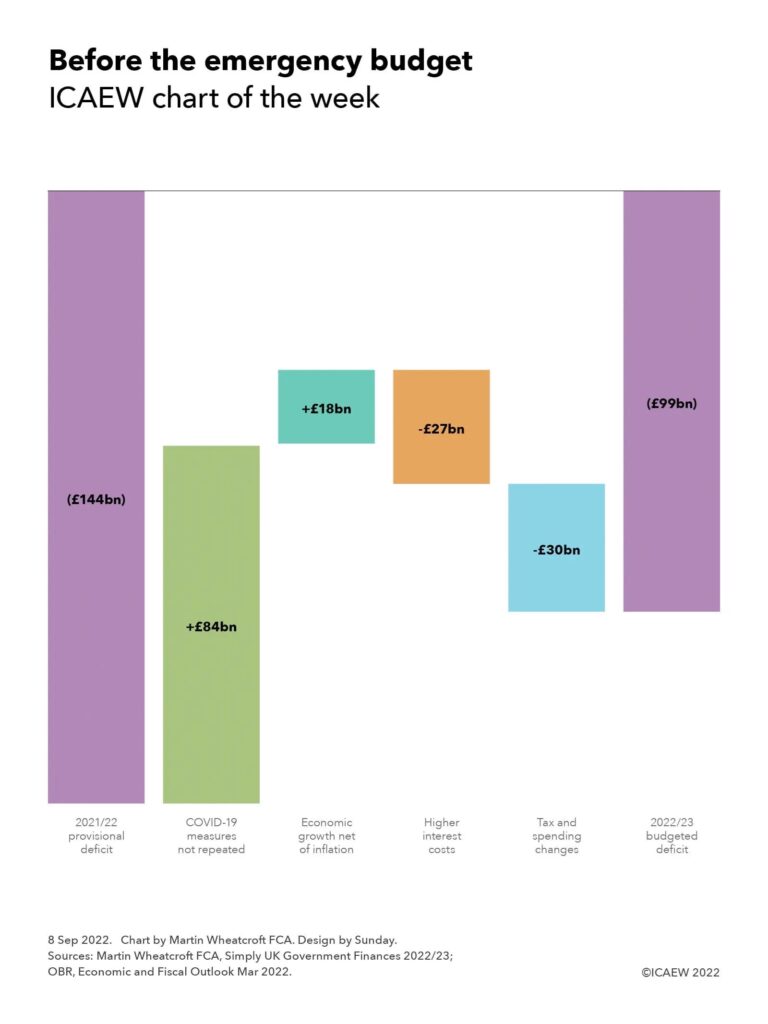

My chart this week looks at how the budgeted deficit was supposed to play out according to the Spring Statement back in March, ahead of an emergency fiscal event expected within the next few weeks.

The new Chancellor will be looking at a range of possible large scale interventions to support individuals and businesses as they face unprecedented cost-of-living and cost-of-doing-business crises this winter. Several commentators have suggested that the combination of tax cuts trailed by new Prime Minister Liz Truss and a massive emergency support package could add more than £100bn to the deficit, more than doubling the budgeted deficit of £99bn established back in March 2022 just before the start of the financial year.

My chart illustrates how the deficit was expected to change from a provisional outturn of £144bn for the deficit in the year ended 31 March 2022, when taxes and other receipts were £914bn and total managed expenditure amounted to £1,058bn.

Last year’s totals included £84bn in COVID-19 related measures (£14bn of tax cuts and £70bn of spending measures) that are not repeated this year, with further spending this year – including continuing to treat COVID-19 patients and tackling NHS backlogs that stem from the pandemic – folded into departmental budgets set during the three-year Spending Review back in October 2021.

Economic growth net of inflation was expected to reduce the deficit by a further £18bn, comprising £21bn in extra receipts from forecast economic growth of 2.2% less £3bn (£41bn on spending, £38bn on receipts) from forecast inflation of 4.1%. The latter uses the GDP deflator measure for the ‘whole economy’ and was estimated at a point when consumer price inflation was expected to reach 8.0% this year.

Inflation also drove much of the jump in interest costs of £27bn in comparison with the previous year, principally because of interest accrued on inflation-linked gilts, but also as a consequence of higher interest rates.

Tax and spending changes amounted to £30bn, comprising £31bn in additional spending less a net £1bn in tax changes. The former comprises a £21bn or 2.0% increase in public spending principally stemming from the 2021 Spending Review, together with £10bn of support for household energy bills announced by former chancellor Rishi Sunak back in February and March 2022. Tax rises were expected to add £20bn to the top line, of which £18bn stems from the rise in national insurance rates from April pending the introduction of the health and social care levy next year. However, this was offset by £19bn in tax cuts and other movements, including a £6bn tax cut from increasing national insurance thresholds, £2bn from cutting fuel duty by 5p, and £1bn from freezing the business rates multiplier.

These changes result in a budgeted deficit of £99bn, being forecast tax and other receipts of £988bn less public spending of £1,087bn.

These amounts exclude £15bn in additional help for energy bills since the budget was finalised in March 2022, partially offset by £5bn from the windfall tax on energy companies announced at the same time. Adjusting for these two items, however, is relatively small beer compared with the large-scale fiscal announcements made by new Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng. This is before the Office for Budget Responsibility works its magic in updating the fiscal forecasts for changes in the economic situation, taking account of higher inflation and interest rates, and lower economic growth or even an economic contraction.

The worsening economic outlook continues to overshadow the public finances, providing perhaps one of the worst foundations for any incoming Chancellor since the Second World War.