Alison Ring, Director for Public Sector at ICAEW, has written to the Chief Secretary to the Treasury ahead of Spending Review 2021 expressing ICAEW’s view that it should be centred on the three key themes of stable funding, fiscal resilience and financial capability.

The first multi-year Spending Review since 2015 offers the government the opportunity to establish a “firm financial platform” to enable the delivery of its key priorities, including recovering from the pandemic and achieving net zero carbon emissions by 2050, according to the ICAEW Public Sector team.

Alison Ring, Director for Public Sector at ICAEW, has written a letter on behalf of the public sector team to the Rt Hon Simon Clarke MP, the newly appointed Chief Secretary to the Treasury, ahead of the Autumn Spending Review 2021, scheduled to conclude on 27 October.

As set out in the letter, ICAEW’s Public Sector team believes the Spending Review should be guided by three key principles:

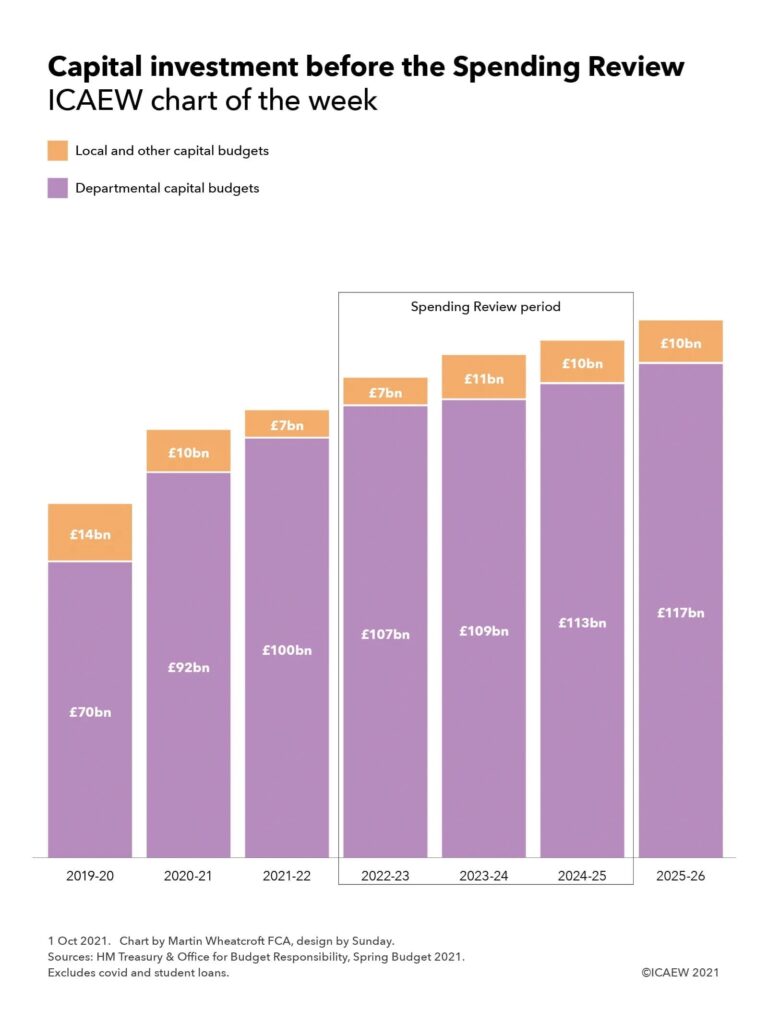

- Stable funding: The Spending Review must provide the certainty that allows bodies across the public sector to plan and invest. The letter argues for the rationalisation of local government funding streams and setting capital budgets over a longer time period.

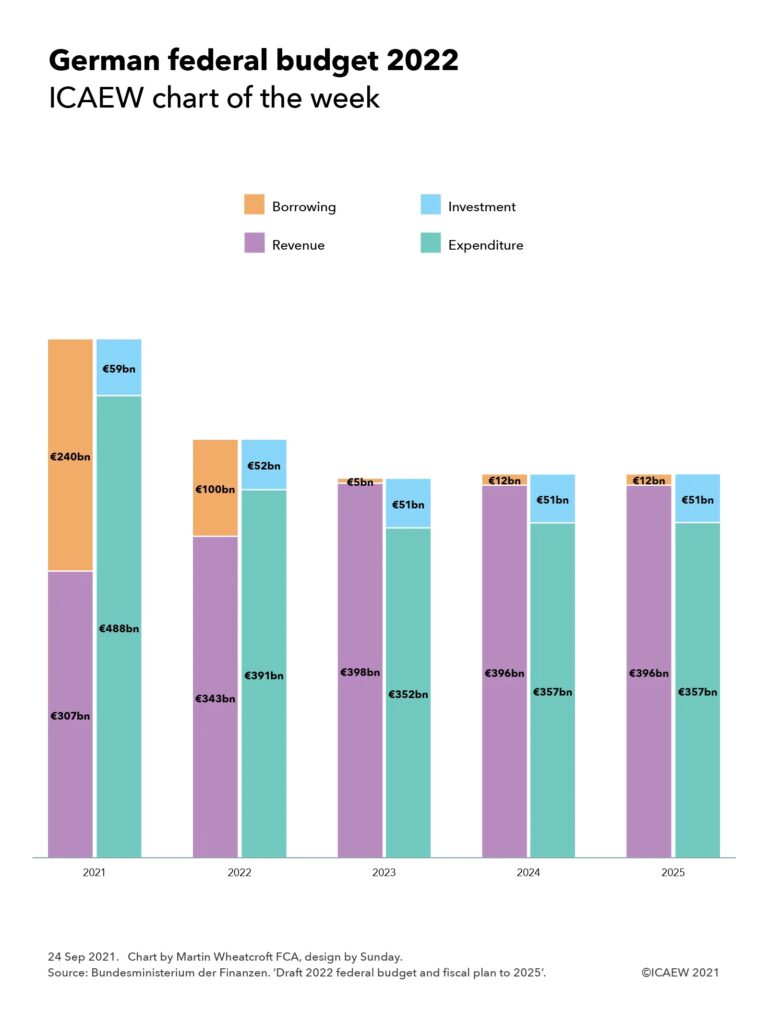

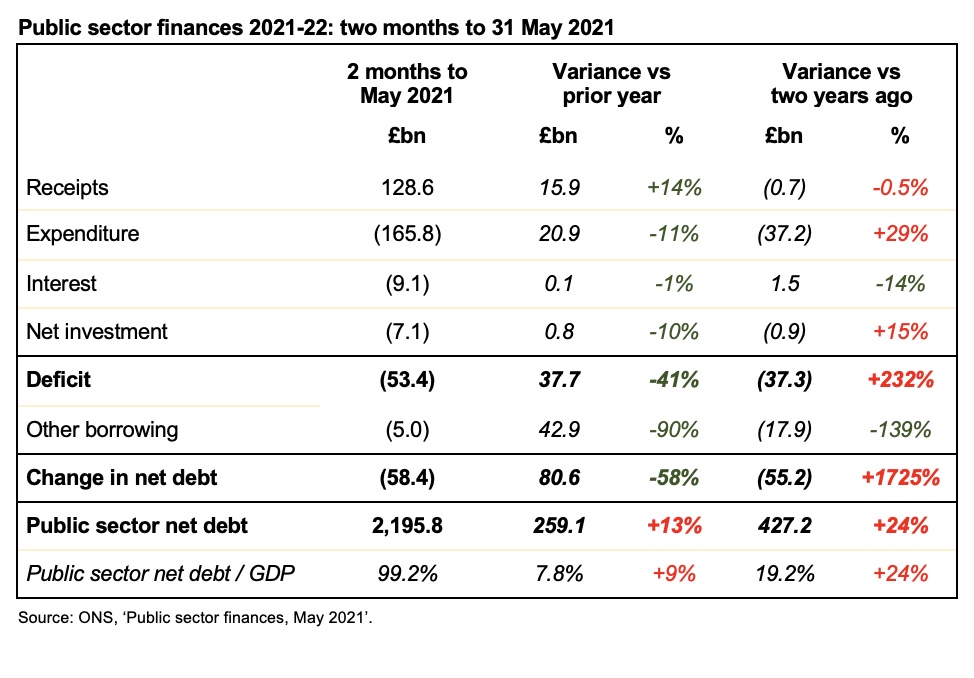

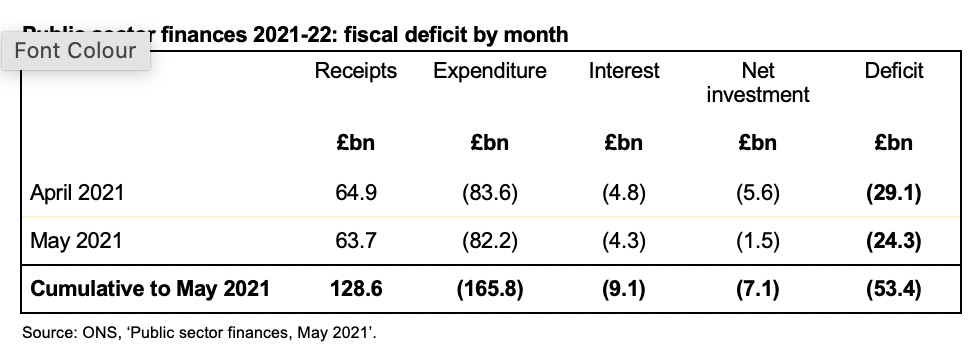

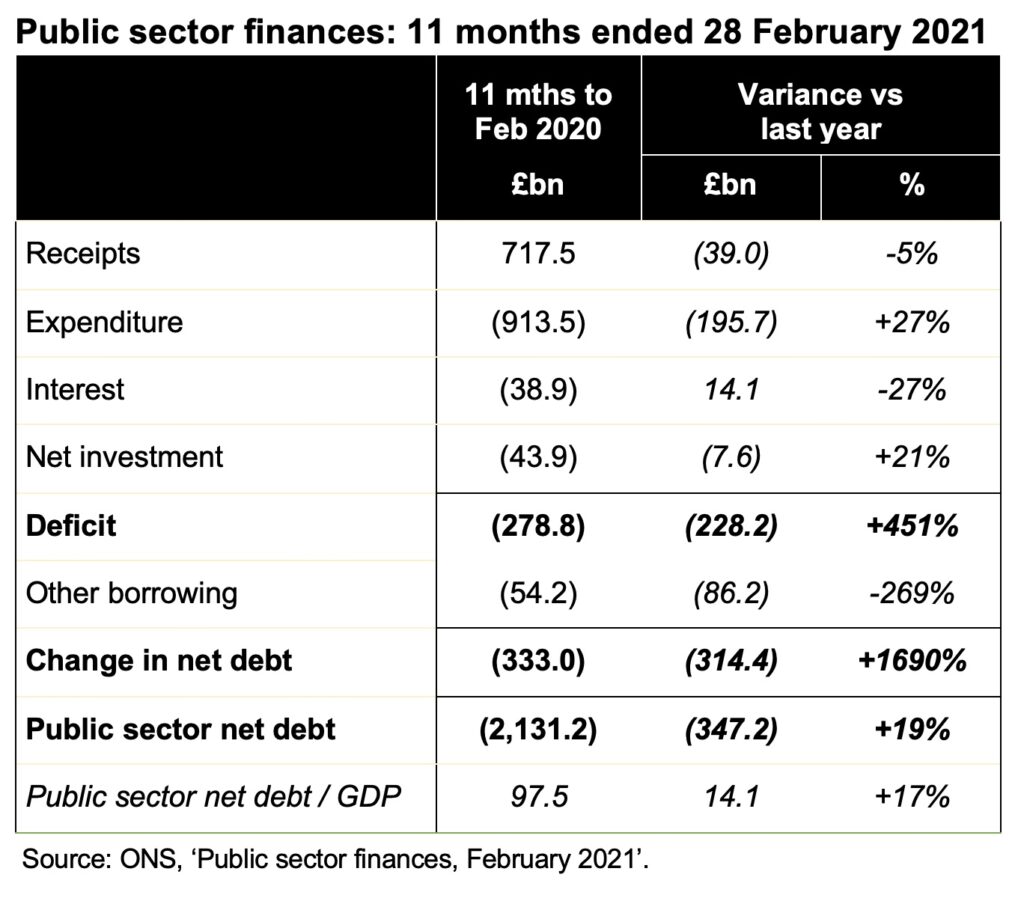

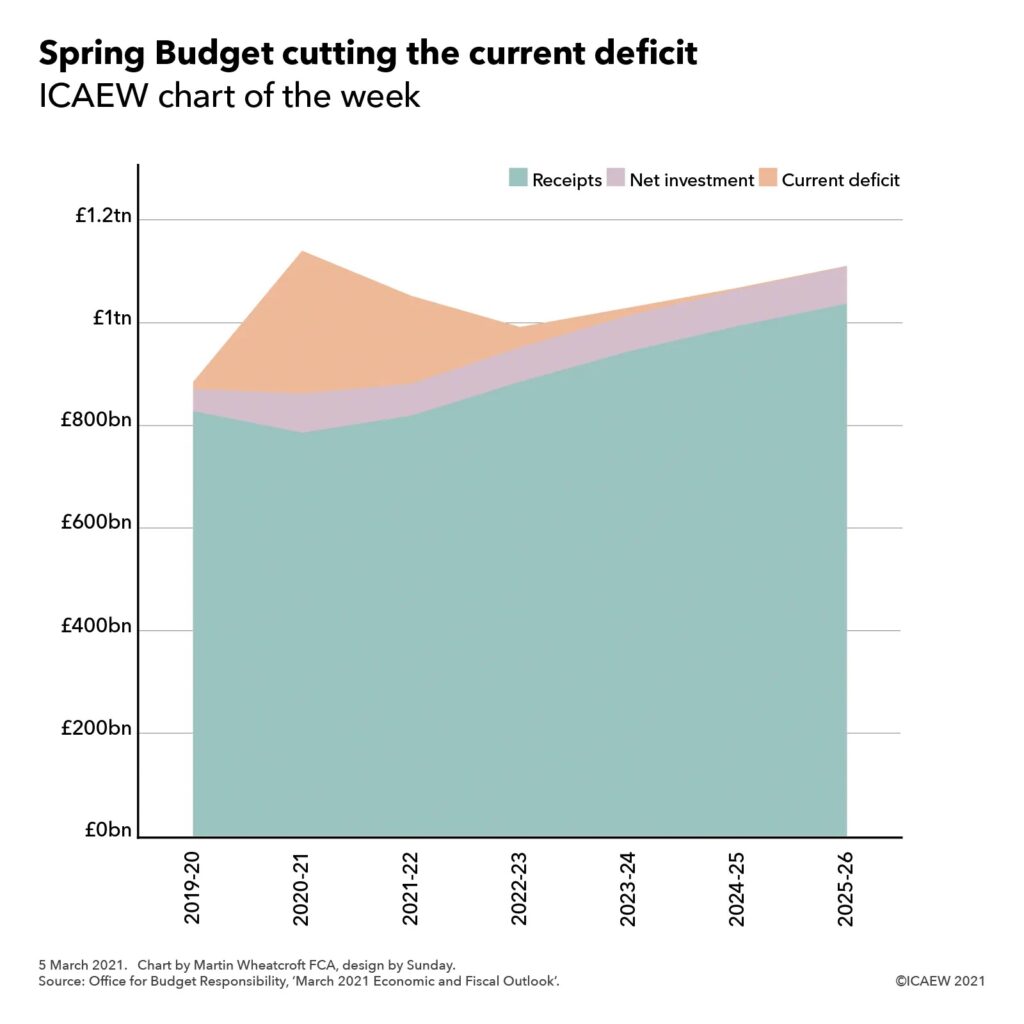

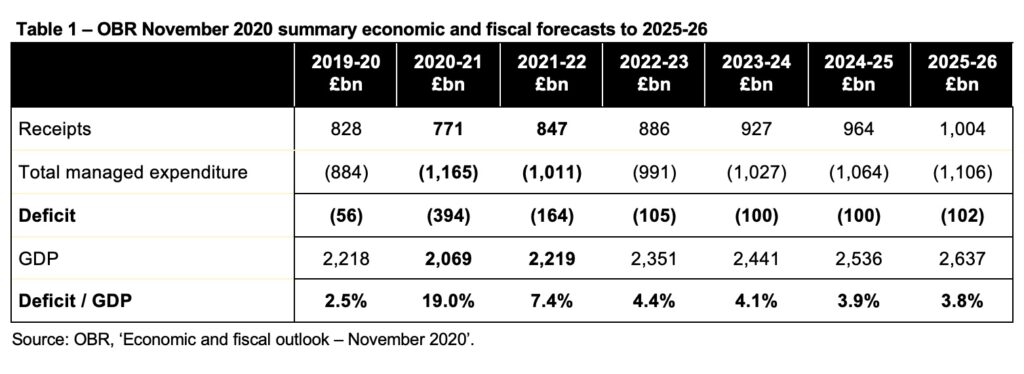

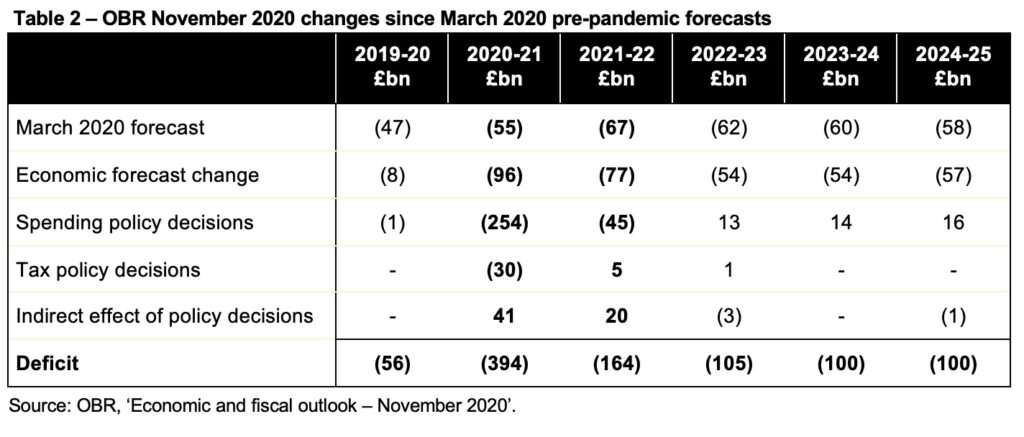

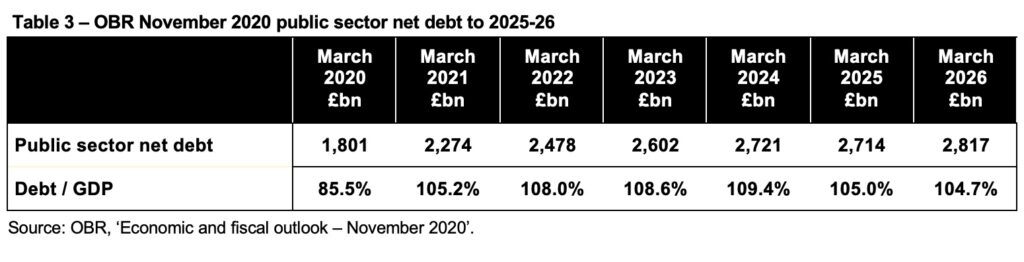

- Fiscal resilience: The government needs to establish a strategy for repairing the public balance sheet following the pandemic and ensure the government has the capacity to withstand future fiscal emergencies. It highlights the urgent need to strengthen local authority balance sheets as the costs of not doing so may be even greater.

- Financial capability: The letter points to recent NAO reports and high profile failures in local government as evidence of the importance of the government using the Spending Review to invest in financial management skills, financial processes, financial reporting and audit.

ICAEW members will be central to ensuring the government can deliver on its priorities. Alison Ring, Director for Public Sector at ICAEW, therefore concludes the letter by offering the Chief Secretary to the Treasury an opportunity to discuss the letter and how ICAEW and its members can support the government in tackling the challenges that the country faces as it recovers from the pandemic.

Alison Ring commented: “The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly weakened the public finances, which hampers the government’s ability to deliver its priorities and respond to future crises. The upcoming Spending Review gives the government the opportunity to establish a long-term strategy for repairing the public balance sheet and providing the financial capability and certainty public sector bodies need to deliver essential priorities such as the transition to net zero carbon by 2050.”

Read the Public Sector team Representation to the Spending Review

See more commentary from ICAEW on the Autumn Budget and Spending Review.