31 July 2020: Summer is the time for a special edition of the #icaewchartofthemonth, celebrating the victory of the English men’s cricket team over the West Indies in the 3rd Test at Old Trafford, resulting in a 2-1 series win for England.

Many explanations of cricket as a sport tend to focus on the intricacies of how it is played but in practice, the aim is pretty simple – one team sets a target by scoring as many runs as they can and the other team then tries to beat that target. Of course, like most sports, the joy is often as much in the skills of the players and the tactics deployed as much as who wins or loses, but the principal objective remains the same: score more runs than the other team.

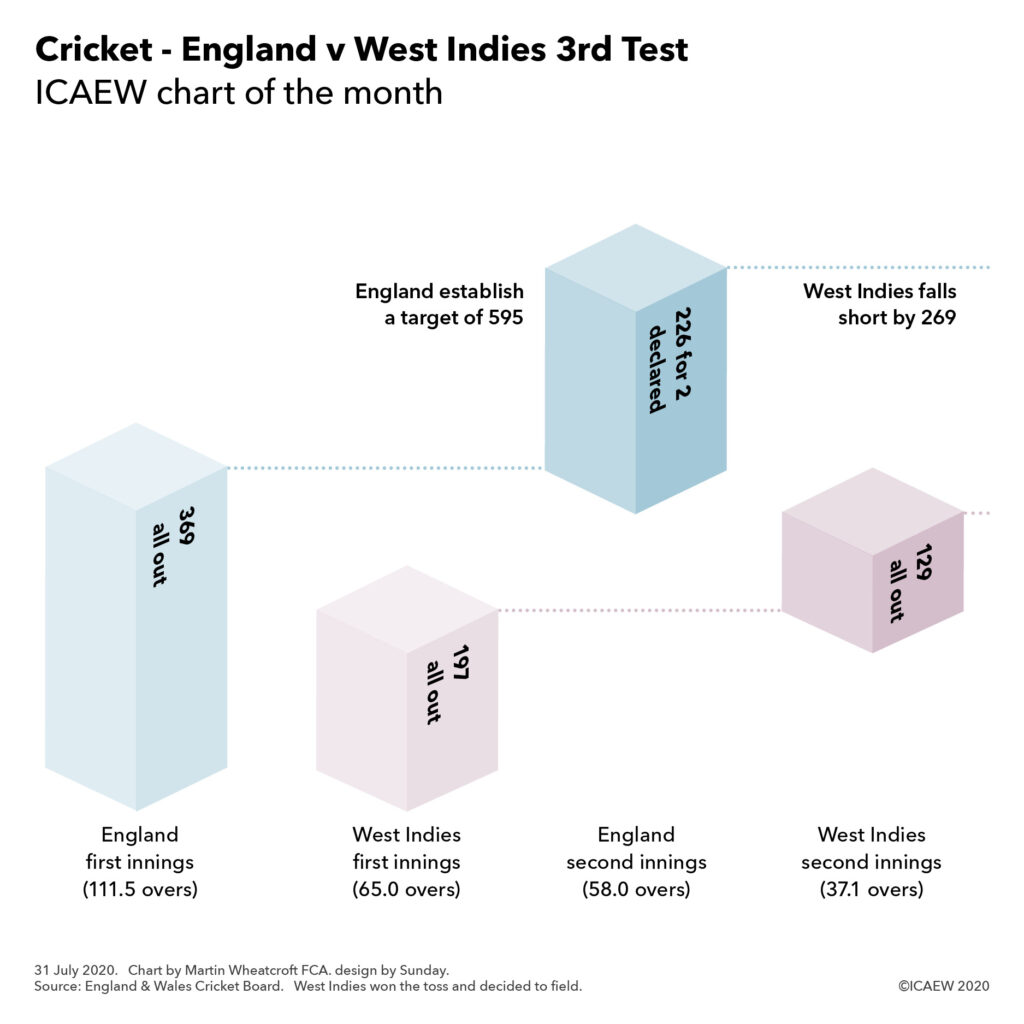

West Indies no doubt regretted putting England into bat first, as England proceeded to score 369 runs in the first innings, significantly better than the 197 the West Indies team achieved in reply. England then extended their total by adding 226 runs before declaring, giving the West Indies a stretching target of 398 to tie or 399 to win. A strong England bowling performance meant West Indies only achieved 129 by the time they were bowled out mid-afternoon on the fifth day, falling short of the overall target of 595 runs by 269.

Stuart Broad had a stand-out match, scoring 62 runs in England’s first innings and taking 6 and 4 wickets respectively in the West Indies’ two innings – including the 500th wicket of his international test career. Chris Woakes, who took 5 of the West Indies’ wickets in their second innings, was the other key English bowler, while Rory Burns (scoring 147 runs across two innings), Ollie Pope (91) and Joe Root (85) were the highest scoring English batsmen. More details are in the scorecard.

Cricket can be a mystery to many, with unique features such as whole days abandoned to rain – as the fourth day of this test match was. Some have even likened cricket to a ritualised rain-dance, helping to make England the green and pleasant land that it is. For others, cricket is a different sort of mystery, providing sporting magic that makes an English summer complete.

The #icaewchartofthemonth and #icaewchartoftheweek will be off for August before returning on Friday 4 September. We hope that you will be able to take some time off to enjoy the summer, wherever and however that may be possible.