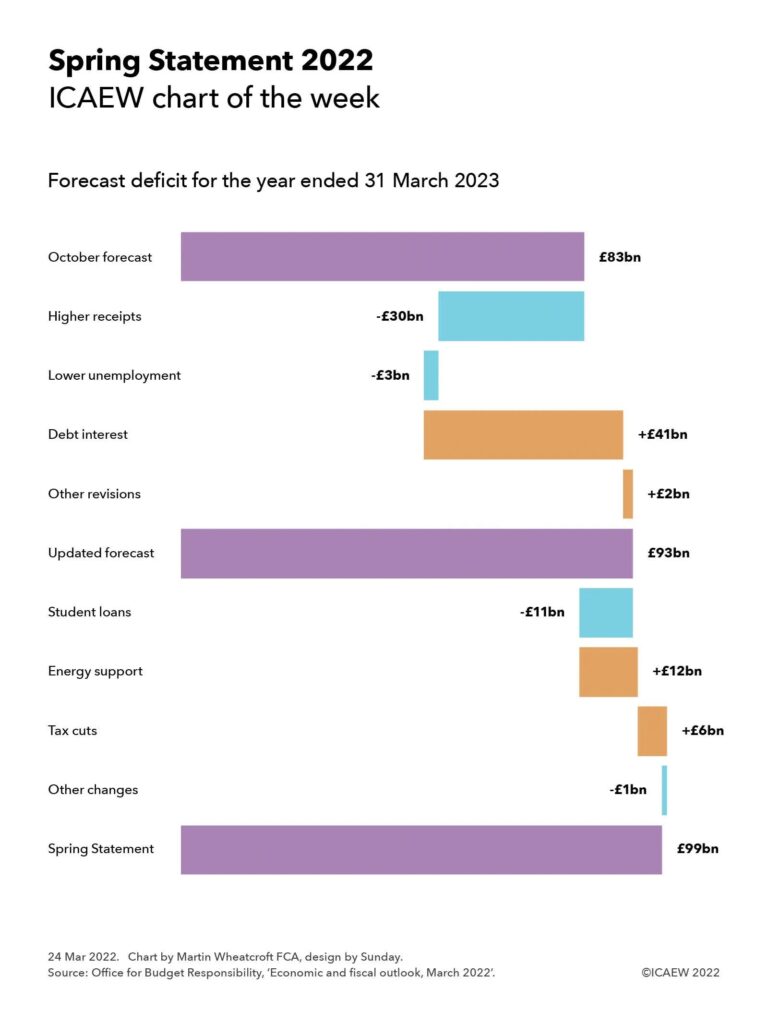

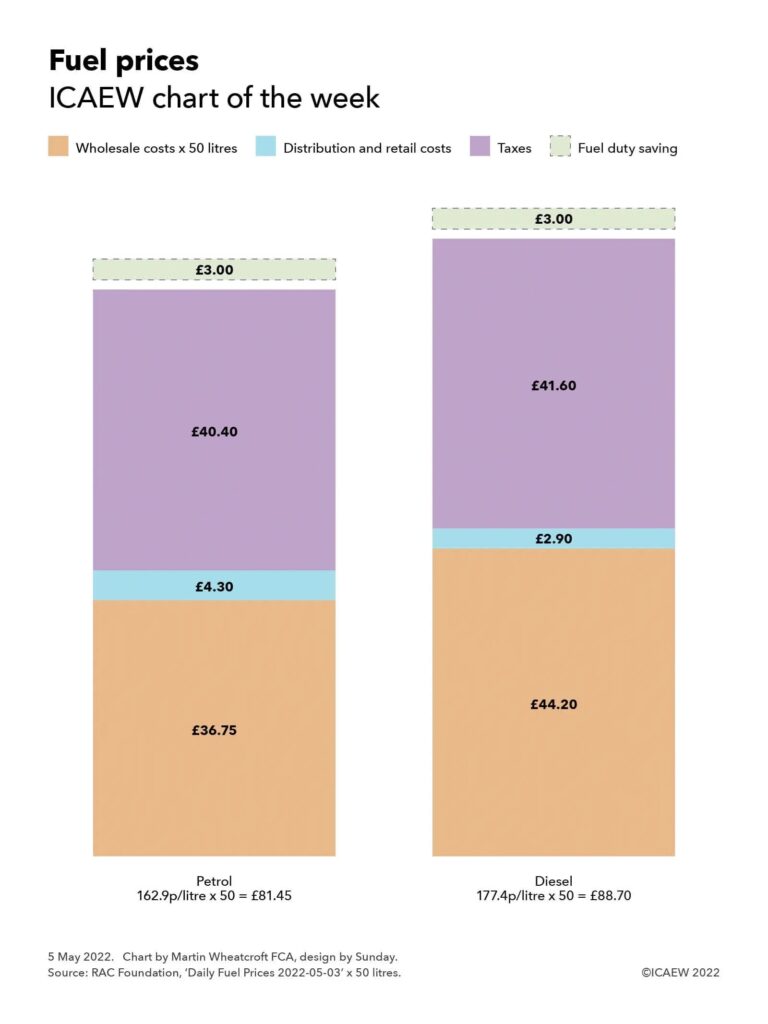

Our chart this week gives a breakdown of what makes up the cost of petrol and diesel, which continue to soar in price despite the temporary cut in fuel duty.

A key component of the cost-of-living crisis is the expense incurred filling up our cars, which has risen by over 50% in two years from approximately 107p a litre for petrol and 112p a litre for diesel back in May 2020 to average prices of 162.9p and 177.4p per litre respectively on 3 May 2022.

Our chart illustrates how much this means in terms of a 50-litre fuel purchase. For petrol, this would have cost an average of £81.45 according to numbers supplied by the RAC Foundation, comprising £36.75 in wholesale costs, £4.30 in distribution and retail costs, and £40.40 in taxes. For diesel, the cost of buying 50 litres would have been £88.70, comprising £44.20 in wholesale fuel costs, £2.90 for distribution and the retailer, and £41.60 in taxes.

In each case, the Chancellor’s temporary 5p cut in fuel duty saves 6p per litre once VAT is taken into account, or £3.00 on a 50-litre purchase.

The wholesale costs of £36.75 and £44.20 (73.5p and 88.4p per litre) for petrol and diesel respectively are made up of £31.30 and £35.55 (62.6p and 71.1p per litre) for refined petrol and diesel and £5.45 and £8.65 (10.9p and 17.3p per litre) for bio content (principally ethanol) included in what you buy at the pump. Distribution and retail costs of £4.30 and £2.90 (8.7p and 5.8p per litre) for petrol and diesel respectively comprise delivery and distribution costs of £0.85 and £1.05 (1.7p and 2.1p per litre) and retailer margin of £3.45 and £1.85 (6.9p and 3.7p per litre).

Taxes of £40.40 and £41.60 (80.7p and 83.2p per litre) comprise fuel duty of £26.45 (52.9p per litre) and £0.35 (0.7p per litre) in greenhouse gas and development fuel obligations for both petrol and diesel, and £13.60 for petrol and £14.80 for diesel (27.1p and 29.6p respectively) in VAT at 20%.

Most of the fuel duty cut has been absorbed by higher wholesale costs, meaning that prices at the pump are only just below their peak immediately prior to the Spring Statement on 23 March. However, retail fuel prices could well go up further in the coming weeks as higher crude oil prices flow through into the cost of refined petrol and diesel in response to EU sanctions against Russian oil.

Taxes on petrol and diesel remain a significant contributor to the public purse, with £26bn expected to be generated in fuel duty in the current fiscal year, despite a decade or so of freezing the rate and the recent temporary cut until March next year. The plan to phase out petrol and diesel vehicles poses a big dilemma for HM Treasury, which will need to make up for lost tax revenues once there is no hydrocarbon fuel to levy duties on.

The current favourite option to fill the gap is road pricing, but the government has yet to formally announce a decision, something that will become more pressing as more and more drivers switch to electric cars.