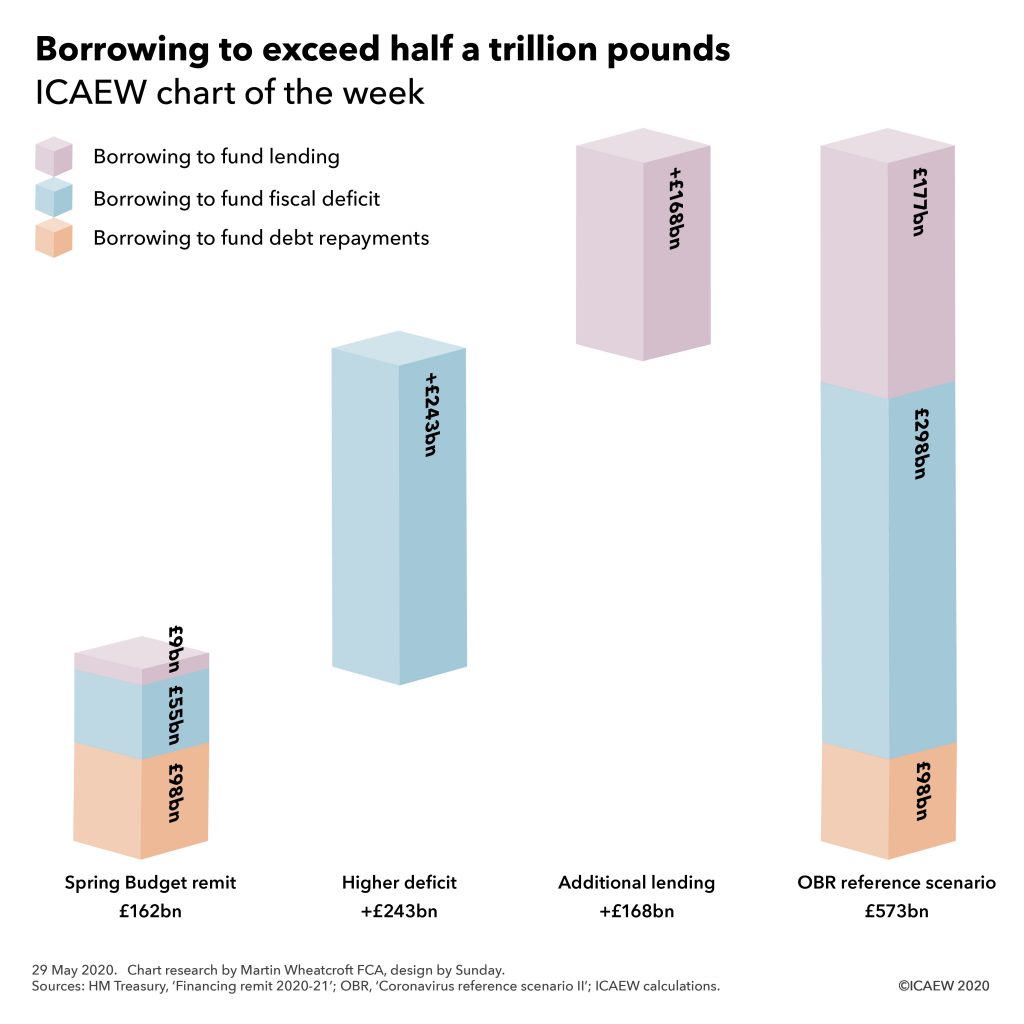

29 May 2020: Government looks to financial markets to fund large-scale fiscal interventions in the economy.

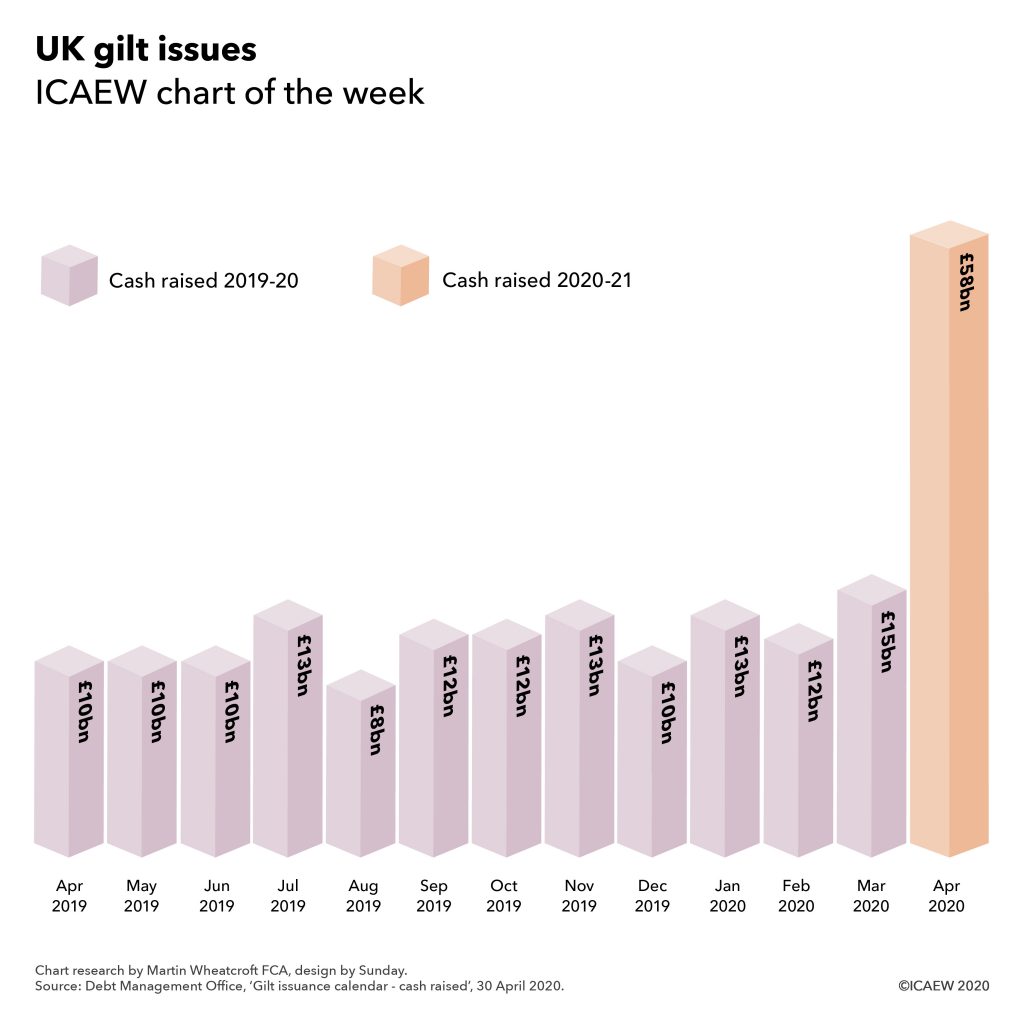

The #icaewchartoftheweek shines a light on the massive expansion in borrowing being undertaken by the UK Government as it seeks to plug an expanding gap between tax receipts and spending and fund a huge amount of loans to banks and businesses in order to try and keep the economy from collapsing.

At the Spring Budget on 11 March, HM Treasury issued a financial remit to the Debt Management Office and National Savings & Investment amounting to £162bn, comprising £98bn to fund the repayment of existing debts, £55bn to fund a planned shortfall between tax receipts and public spending (the deficit), and £9bn to fund public lending to individuals and businesses.

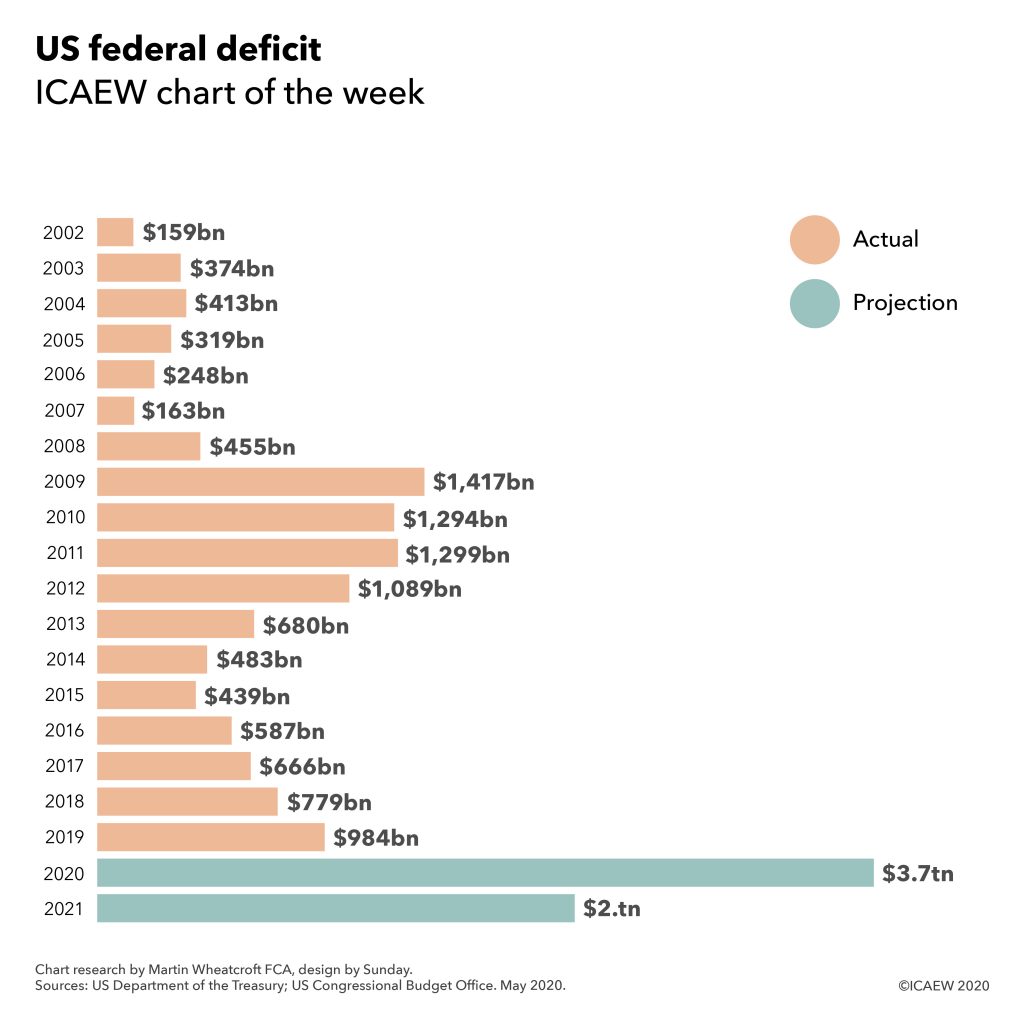

Since then the fiscal situation has transformed, with the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) suggesting that the deficit could increase by as much as £243bn to £298bn in 2020-21, while lending activities could increase by a further £168bn to £177bn. Public sector net debt at 31 March 2021 might increase by £411bn from the Spring Budget forecast of £1,819bn to £2,230bn.

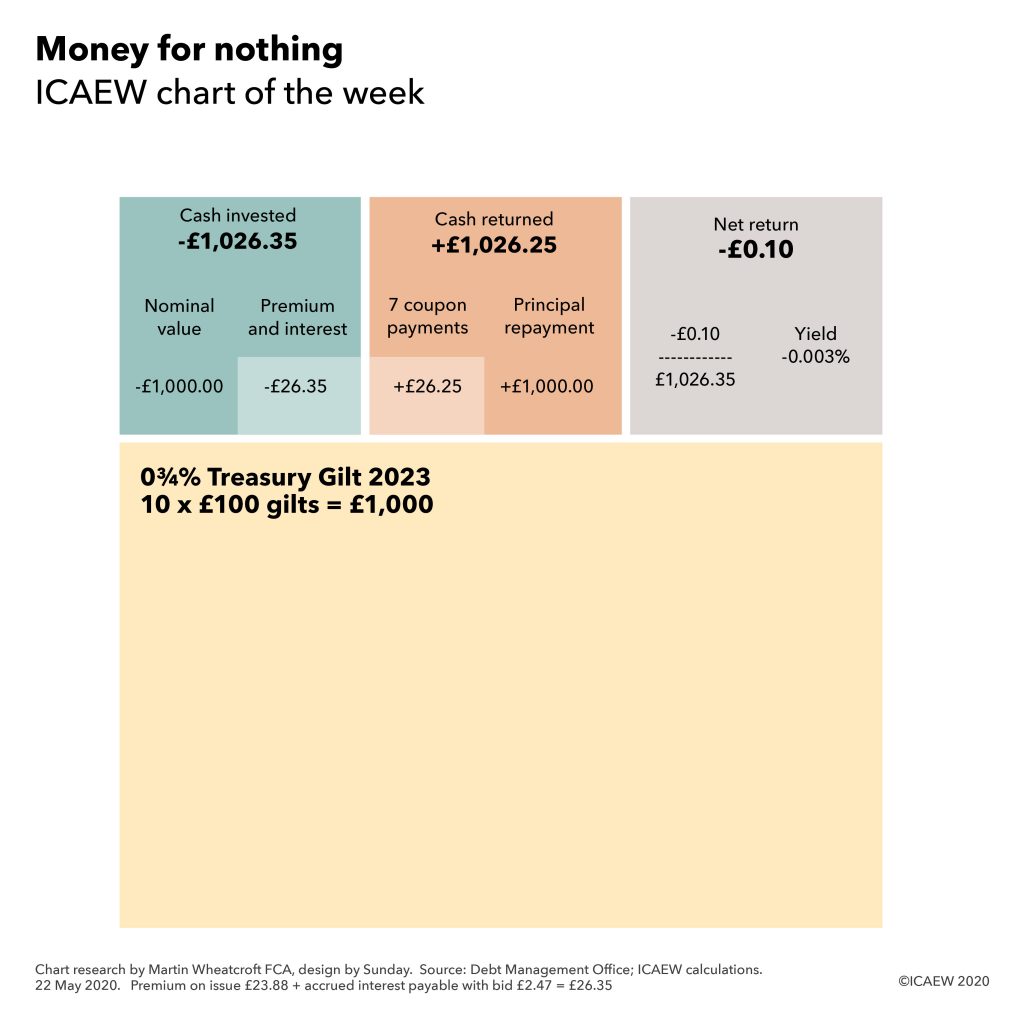

The good news is that the cost of this borrowing is relatively small, with yields on ten-year gilts as low as 0.20%.

To find about more about the global and UK fiscal crisis read the ICAEW Fiscal Insight on coronavirus and public finances.