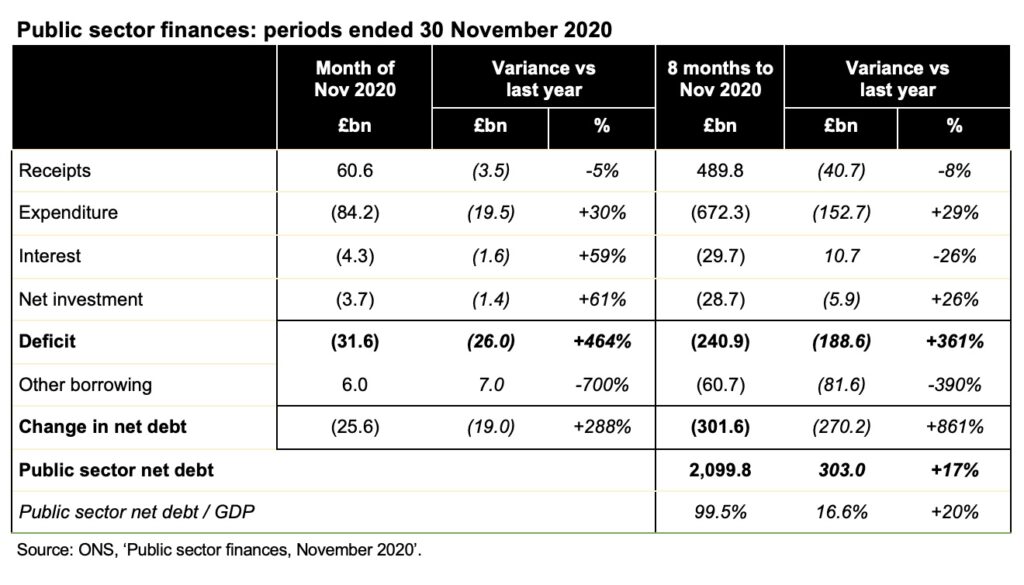

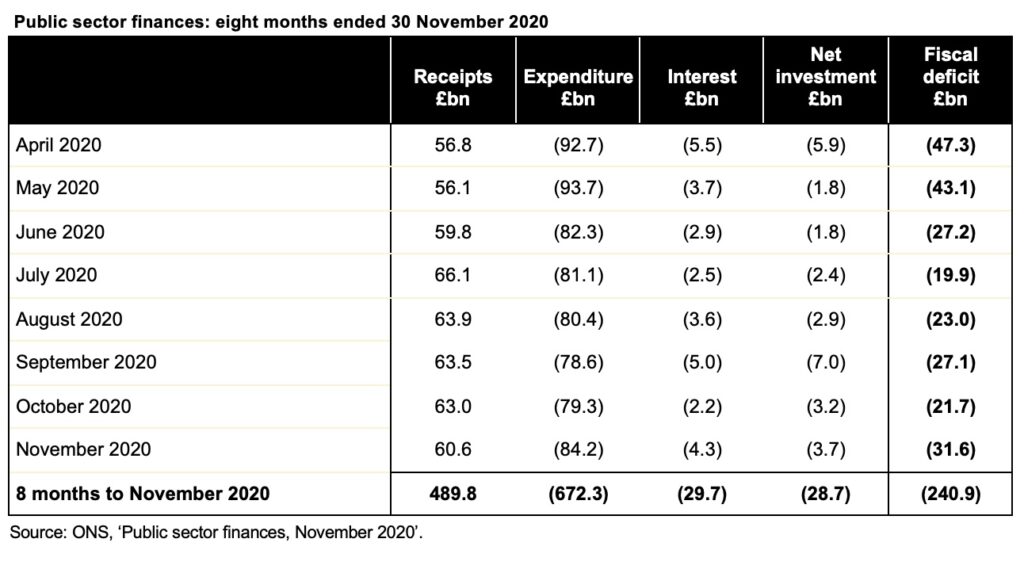

23 December 2020: The UK public sector incurred a £31.6bn deficit in November, bringing the total shortfall over eight months to £240.9bn. Debt reached an all-time high of £2.1tn.

Commenting on the latest public sector finances for November 2020, published on Tuesday 22 December 2020 by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), Alison Ring sector director at ICAEW, said:

“A slightly more optimistic forecast for GDP from the Office for Budget Responsibility last month resulted in the UK’s debt to GDP ratio being revised downwards, despite public sector debt having reached an all-time high of £2.1tn in November. However, this optimism may prove to have been premature, with reports suggesting another national lockdown in the new year and disruption in international trade foretelling a potentially difficult winter ahead for the economy and the public finances.

Prospects for the spring will depend on how quickly the vaccine can be rolled out, whether testing and tracing can deliver rapid and reliable results, and the extent to which disruption at borders now and after 1 January can be minimised.”

Public sector finances for November

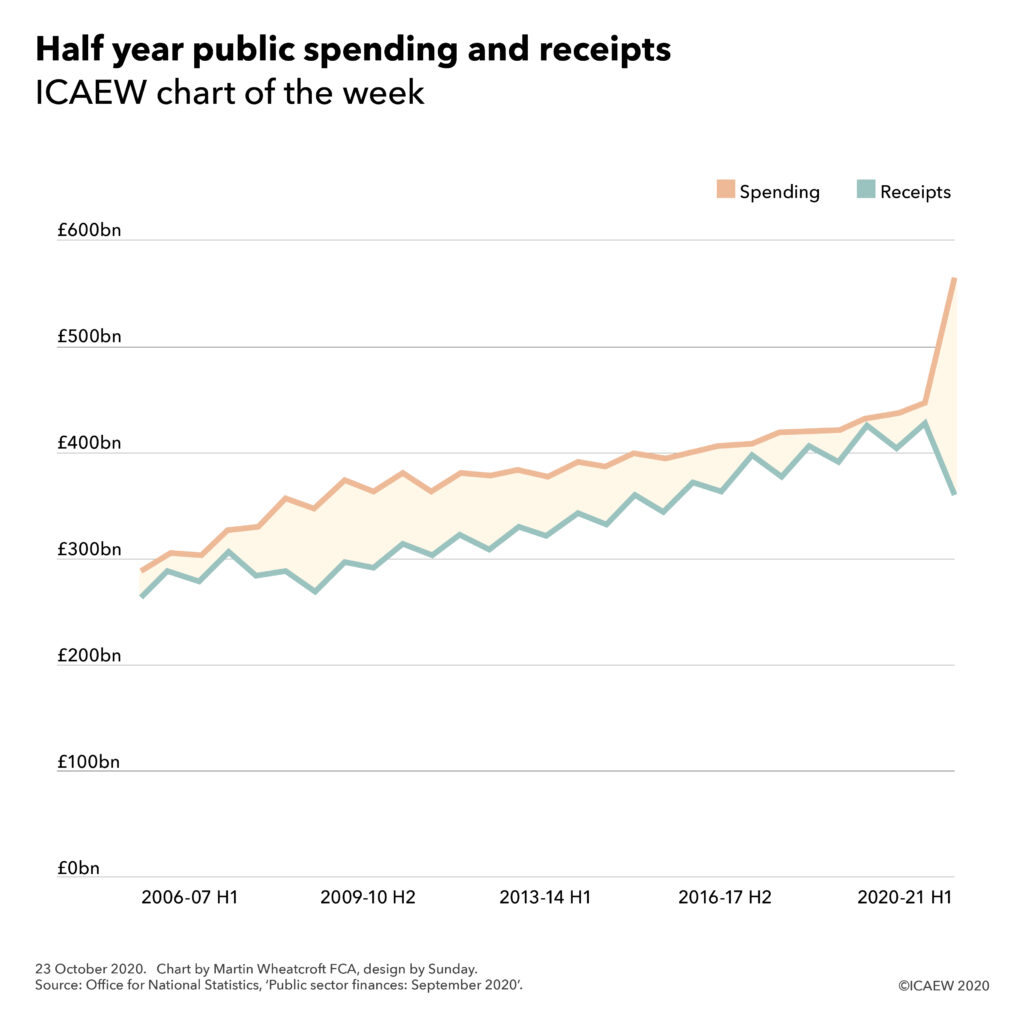

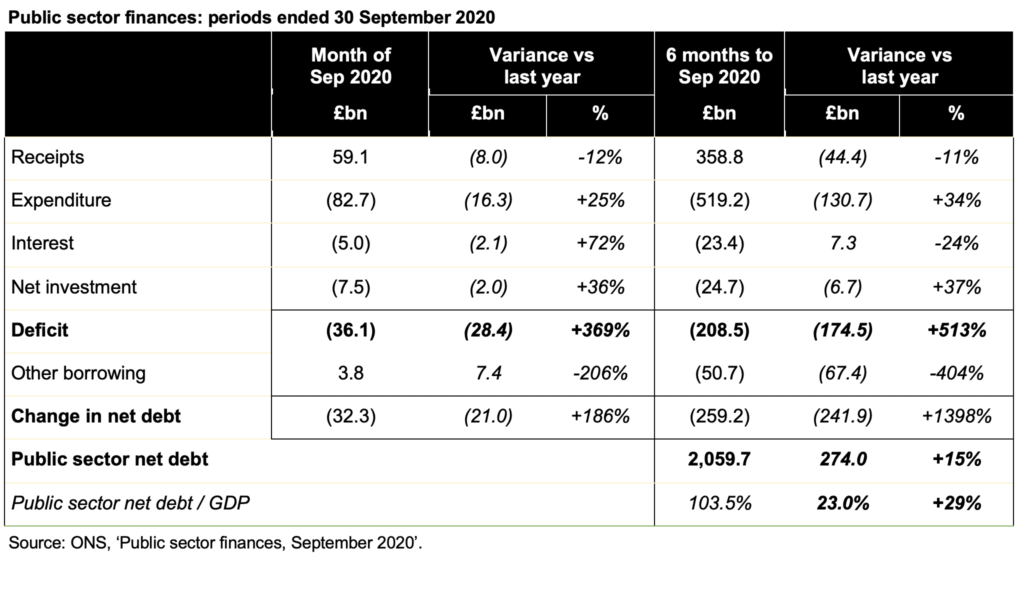

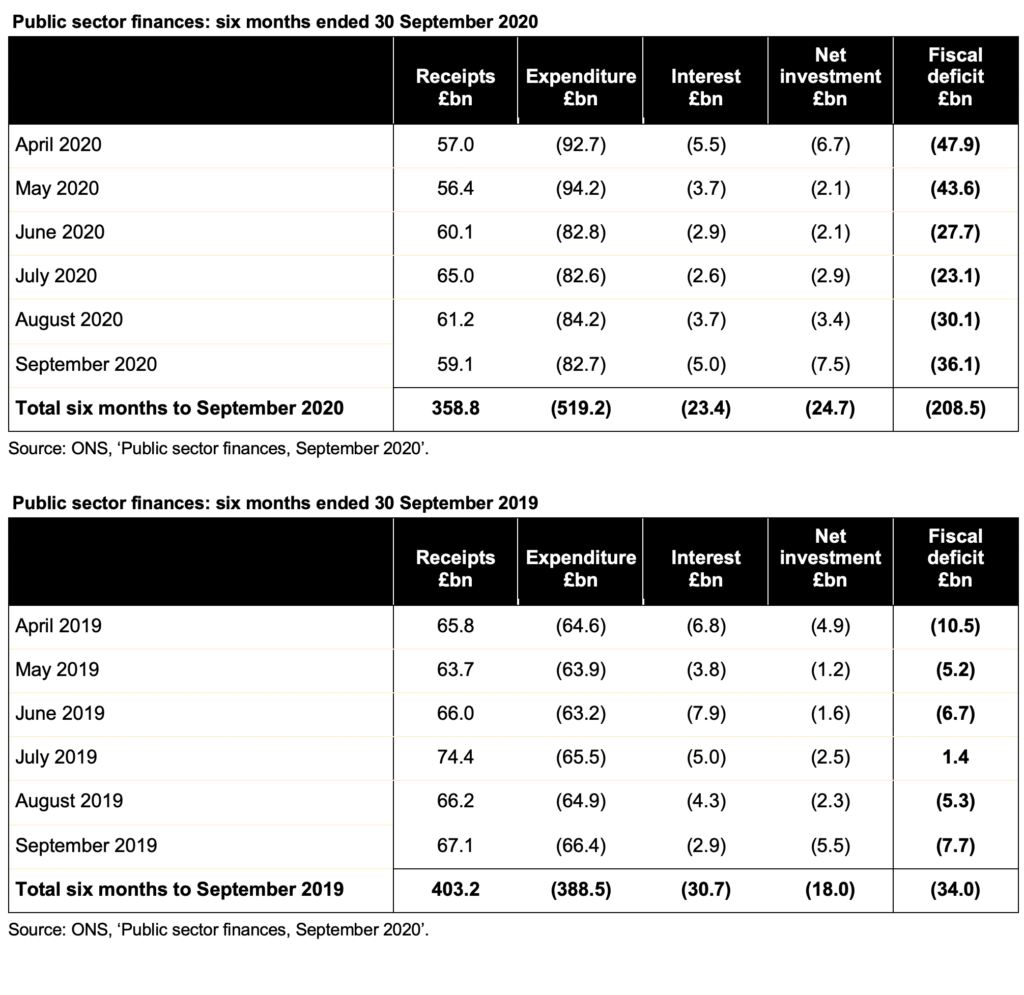

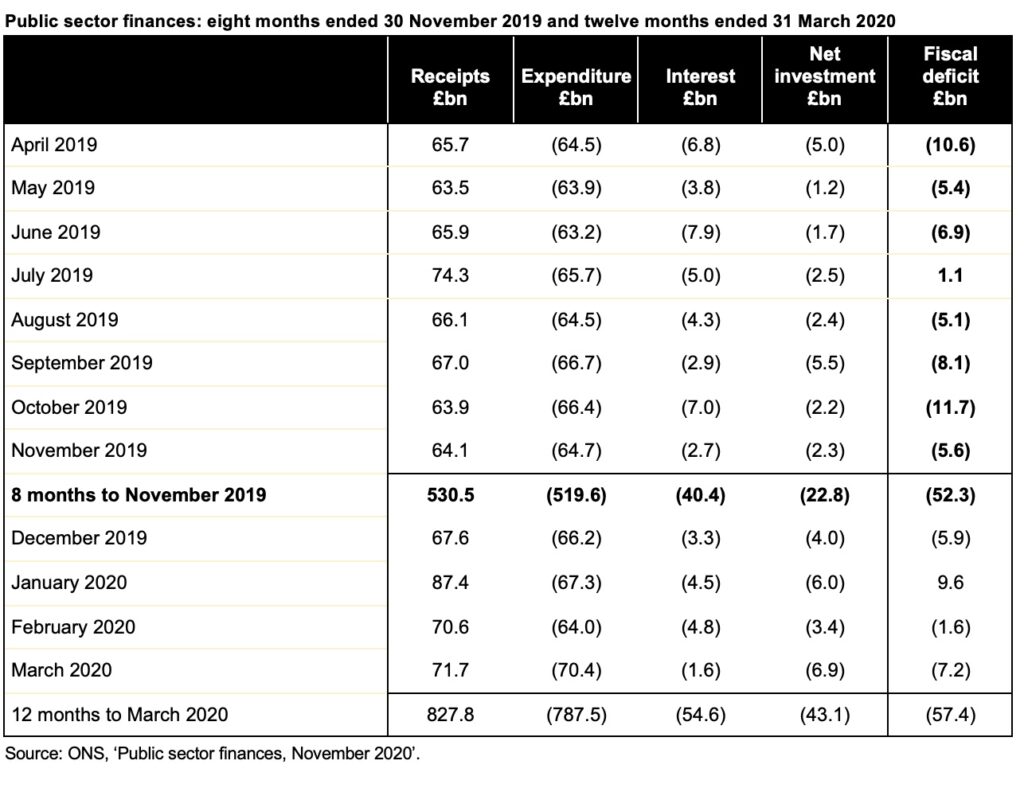

The latest public sector finances reported a deficit of £31.6bn in November 2020, a cumulative total of £240.9bn for the first eight months of the financial year. This is £188.6bn more than the £52.3bn recorded for the same period last year.

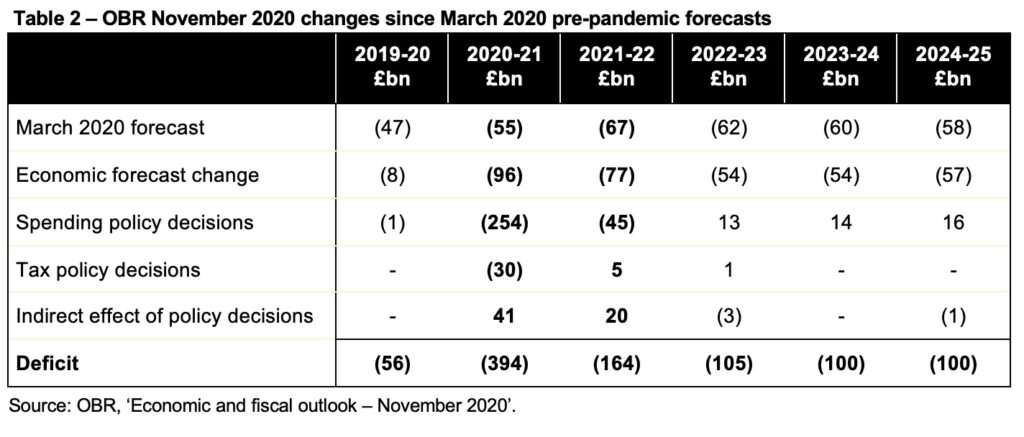

Falls in VAT, corporation tax and income tax drove lower receipts, while large-scale fiscal interventions resulted in much higher levels of expenditure. Net investment is greater than last year, as planned, while the interest line has benefited from ultra-low interest rates.

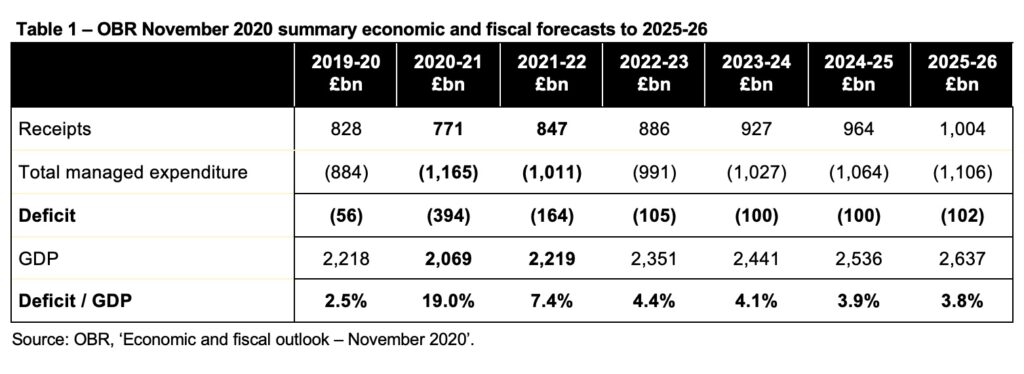

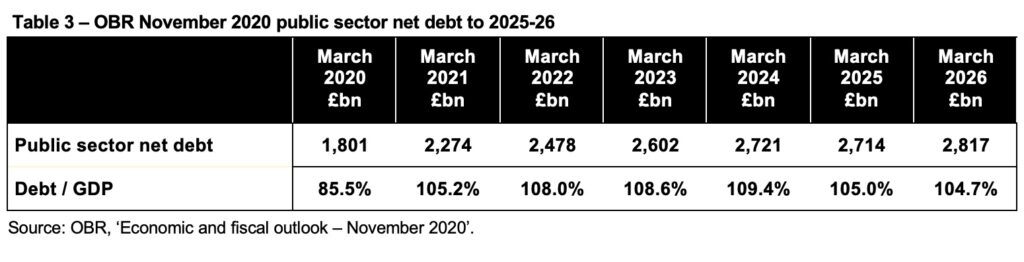

Public sector net debt increased to £2,099.8bn or 99.5% of GDP, an increase of £301.6bn from the start of the financial year and £303.0bn higher than in November 2019. This reflects £60.7bn of additional borrowing over and above the deficit, most of which has been used to fund coronavirus loans to business and tax deferral measures.

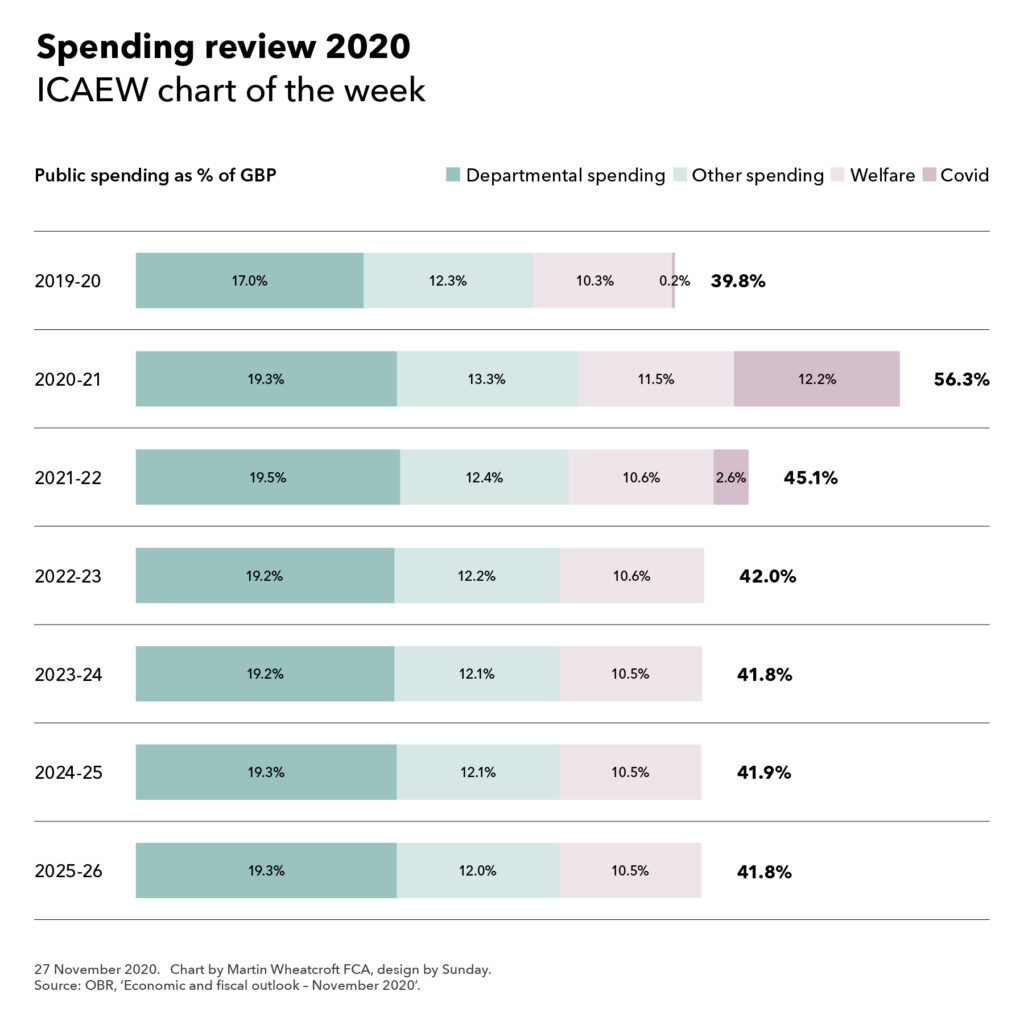

The combination of receipts down 8%, expenditure up 29% and net investment up 26% has resulted in a deficit for the eight months to November 2020 that is over four times the budgeted deficit of £55bn for the whole of the 2020-21 financial year set in the Spring Budget in March, despite interest charges being lower by 26%. The cumulative deficit is approaching five times as much as for the same eight-month period last year.

Cash funding (the ‘public sector net cash requirement’) for the month was £20.7bn, bringing the cumulative total this financial year to £295.8bn, compared with £14.9bn for the same eight-month period in 2019.

Interest costs have fallen despite much higher levels of debt, with extremely low interest rates benefiting both new borrowing to fund government cash requirements and borrowing to refinance existing debts as they have been repaid.

The deficit remains on track to approach the £393.5bn forecast for the financial year to March 2021 by the Office for Budget Responsibility in the Spending Review once bad debts not yet recognised on coronavirus loans are included.

Upwards revisions to GDP based on the latest Office for Budget Responsibility forecasts have reduced the debt to GDP ratio for this and previous months to below 100% of GDP. However, the likelihood of a further national lockdown in the new year and for disruption in international trade with the end of the EU transition period could depress prospects for GDP growth in 2021.

Caution is needed with respect to the numbers published by the ONS, which are expected to be repeatedly revised as estimates are refined and gaps in the underlying data are filled.

The ONS made a number of revisions to prior month and prior year fiscal numbers to reflect revisions to estimates and changes in methodology. These had the effect of reducing the reported fiscal deficit in the first seven months from the £214.9bn reported last time to £209.3bn and increasing the reported deficit for 2019-20 from £56.1bn to £57.4bn.