3 August 2020: Chief Secretary to the Treasury Steve Barclay delivered his first speech last week, providing fresh detail on the plan for the Spending Review.

Steve Barclay’s first speech as Chief Secretary, delivered to thinktank Onward on Tuesday 28 July 2020, set out how he believes Treasury can be an accelerator of change in government.

He sees the Spending Review as a significant moment in the lifecycle of any government, but with the current review being conducted against the backdrop of the most challenging peacetime economic circumstances in living memory.

Despite that, the Government believes the recovery from this pandemic can be a moment for national renewal, with the Spending Review acting as the mechanism to deliver the Prime Minister’s ambition to ‘level up’ the country.

As a constituency MP, Barclay said he has run up against a system that is slow and siloed. By way of an example, he asked why there is a seven-year gap between funding being agreed for a road scheme and the first digger arriving? Or why it takes a decade to decide to produce a full business case on whether to re-open eight miles of railway track?

The lack of upfront clarity on outcomes, the slow speed of delivery and the variable quality of data within government are all areas the Spending Review provides an opportunity to challenge.

The Chief Secretary stressed that to ‘level up’ the country properly, the Government needs to ensure that Treasury decision-making better reflects the UK’s economic geography, with more balanced judgments taking into consideration the transformative potential of investment to drive localised growth.

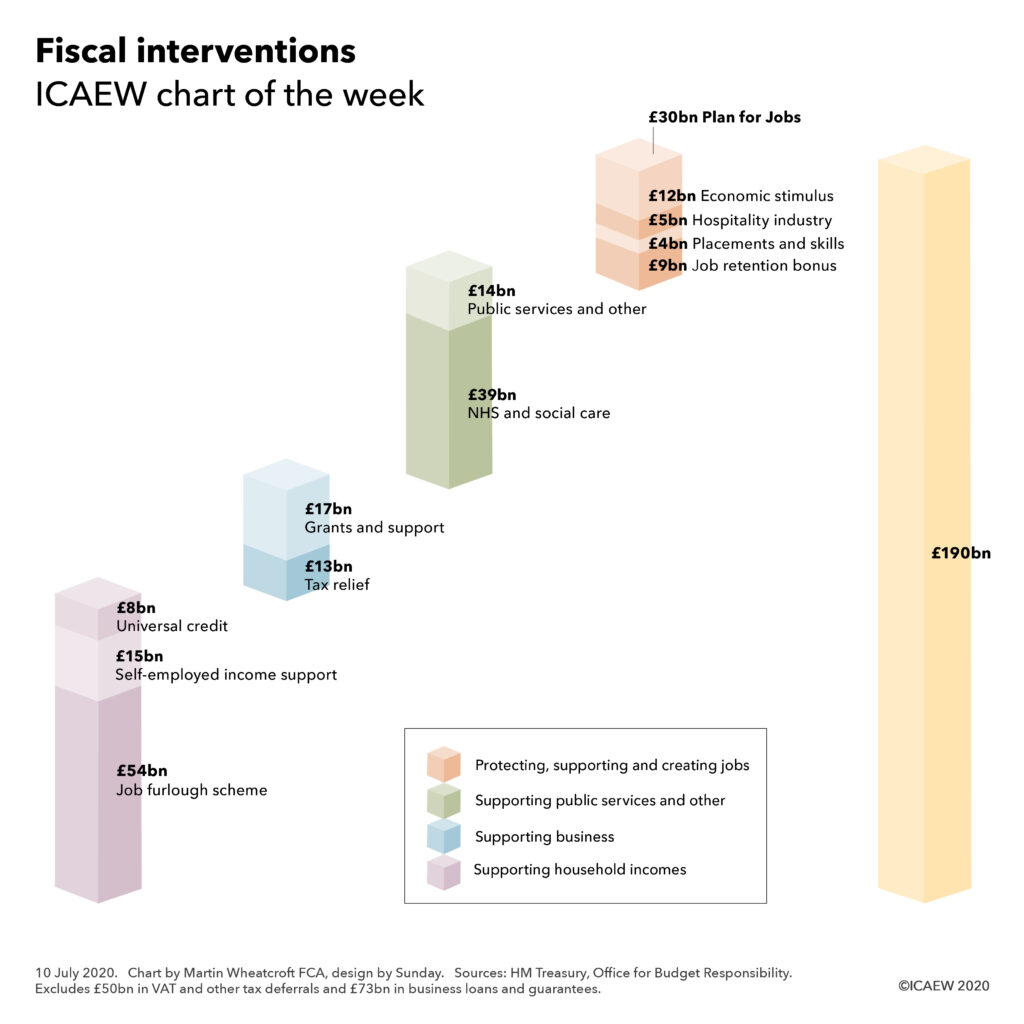

He drew on the speed of change during the pandemic, with the furlough scheme taking just one month from being announced to being opened for applications when normally such schemes take months – years even – to deliver.

He asked if the wheels of government can be made to spin this fast in a crisis, with all the added pressures of lockdown, why can’t it happen routinely?

Time to level up

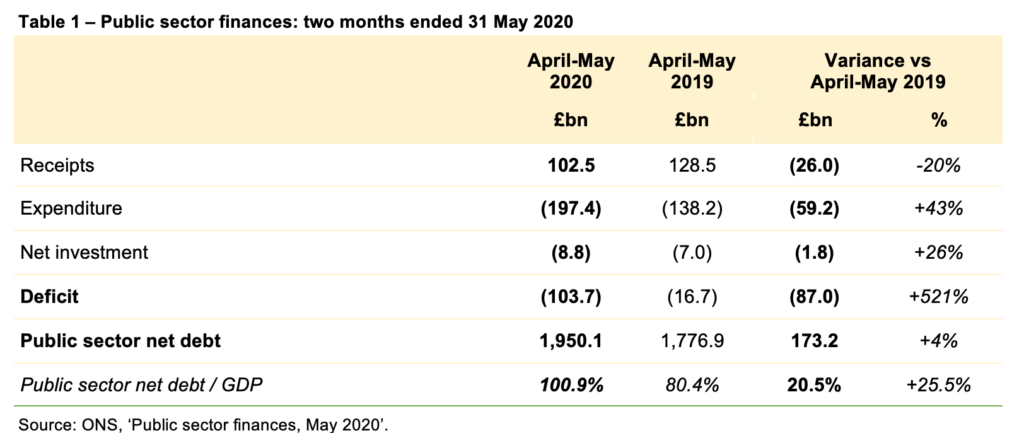

The Chief Secretary stated that the actions being taken to support businesses and jobs during the pandemic are the right thing to do, even though it comes at a cost. The cost of inaction would be far greater, he claimed.

Even though the Prime Minister has made it clear that austerity is not the answer to navigating a much-changed economic landscape, departments will have to make tough choices in the months ahead.

The commitment to reviewing the Green Book investment manual was reiterated with changes planned to allow room for more balanced judgments on investments to reduce inequality and drive localised growth.

During the speech, Barclay listed several priorities for government in the Spending Review:

- accelerating the UK’s economic recovery;

- levelling-up opportunity across the country;

- improving public services; and

- making the UK a scientific superpower.

Outcomes, speed and data

To achieve these objectives, the Chief Secretary focused on three key approaches: outcomes, speed and data.

On outcomes, the Spending Review would try to tie expenditure and performance more closely together, with Treasury having clearer sight of both intended outcomes and subsequent evaluation of their delivery.

For some of the most complex policy challenges, this will involve breaking the silos between departments, and pilot projects are currently being used to test innovative ways of bringing the public sector together.

On speed, Barclay noted that this is a ‘hallmark of the digital era’. Programmes need to start with robust goals and the temptation to repeatedly change plans has to be resisted if the UK is to bring down capital costs that are typically between 10% and 30% higher than in other European countries. A new Infrastructure Delivery Task Force (known as Project Speed) will be established to cut down the time it takes to develop, design and deliver vital projects.

This will involve more standardisation and modularisation between projects, for example in speeding housing construction. The Spending Review will seek to accelerate the adoption of Modern Methods of Construction and explicitly link funding decisions to schemes that priorities it.

On data, the Chief Secretary believes that government is behind the curve when it comes to obtaining, analysing, and enabling access to open data. It remains the case that decisions still rely heavily on spreadsheets from departments rather than data directly sourced in real time. Work has already begun to incentivise departments and arms-length bodies to supply higher quality standardised data and to support the Treasury to better interrogate this data.

Building this will involve sorting out the data architecture as well as the data sets, and the Spending Review will focus on addressing legacy IT and investing in the data infrastructure needed to become a “truly digital government”.

The new radicals

Barclay concluded with stressing the importance of taking risks, setting ambitious goals and experimenting with ways of delivery, even if failure is a possibility. He wants to move beyond a simple yes/no approach to public spending and instead bring together people, ideas and best practice from inside and outside government.

He concluded: “This is an opportunity for the Treasury to capture the ‘can do’ attitude shown by civil servants during the COVID pandemic and make it permanent. To be the new radicals, leading change across government.

“Done well, we can move on from an era of spreadsheets. We can create a smarter and faster culture in Whitehall. And we can ensure that Britain does indeed bounce back from this crisis stronger and better than before.”

Speech by Steve Barclay MP, Chief Secretary to the Treasury, on 28 July 2020.