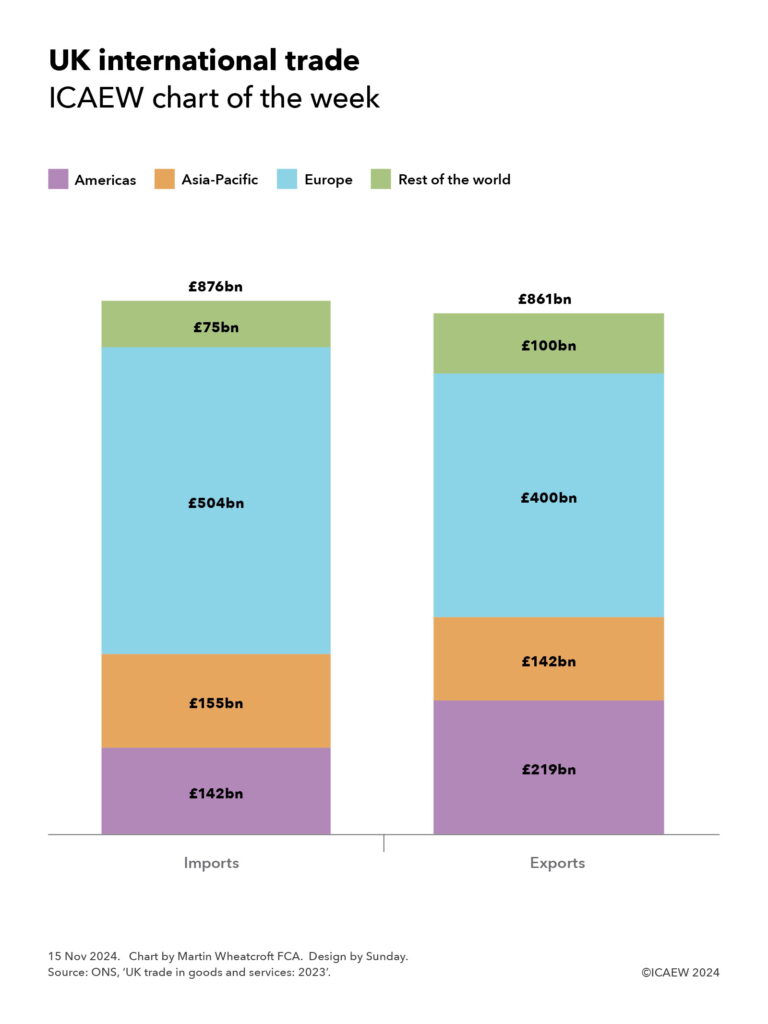

My chart for ICAEW this week is inspired by International Trade Week and looks at where UK imports come from and exports go to, ahead of what might be some major changes in US trade policy when President-elect Trump assumes office on 20 January 2025.

My chart of the week illustrates how UK imports in 2023 totalled £876bn, £15bn more than total exports of £861bn.

Imports comprise £142bn (16%) from the Americas, £155bn (18%) from Asia-Pacific, £504bn (57%) from European countries, and £75bn (9%) from the rest of the world. Exports comprise £219bn (25%) to the Americas, £142bn (16%) to Asia-Pacific, £400bn (46%) to European countries, and £100bn (12%) to the rest of the world.

Imports can be analysed between £581bn in goods and £295bn in services, while exports can be broken down into £393bn in goods and £468bn in services, meaning the UK had a trade deficit of £188bn in goods and a trade surplus of £173bn in services in 2023.

The UK’s largest overall trade partner is the EU, which makes up most of the UK’s trade with countries in Europe, while its largest individual trade partner is the US. Excluding Germany (the largest country in the EU), the UK’s next largest trade partner is China. Together, imports from these three economies add up to £635bn or 72% of the total, while exports to the US, EU and China equate to £594bn or 69% of the total.

International Trade Week is an opportunity to celebrate the successes of the UK’s importers in sourcing the goods and services that individuals and businesses need and of the UK’s exporters in selling goods and services around the world.

However, this time around all eyes are on the result of the US general election, and what the potential trade policies of the incoming US administration under Donald Trump might mean for the UK. Not only could they result in major changes in how trade is conducted between the UK and the US (17% of our total trade), but also between the UK and the EU (46%), and between the UK and China (7%).

We trade in interesting times.

Major trading partners

Americas

US – £115bn imports (£58bn goods, £57bn services); £187bn exports (£60bn goods, £127bn services)

Canada – £9bn imports (£5bn goods, £4bn services); £16bn exports (£7bn goods, £9bn services)

Brazil – £5bn imports (£4bn goods, £1bn services); £6bn exports (£3bn goods, £3bn services)

Other countries in the Americas – £13bn imports (£7bn goods, £6bn services), £10bn exports (£5bn goods, £5bn services)

Asia-Pacific

China (including Hong Kong) – £69bn imports (£61bn goods, £8bn services); £51bn exports (£32bn goods, £19bn services)

India – £24bn imports (£10bn goods, £14bn services); £16bn exports (£6bn goods, £10bn services)

ASEAN – £22bn imports (£14bn goods, £8bn services); £25bn exports (£12bn goods, £13bn services)

Japan – £14bn imports (£8bn goods, £6bn services); £14bn exports (£6bn goods, £8bn services)

Australia – £6bn imports (£2bn goods, £4bn services); £15bn exports (£5bn goods, £10bn services)

South Korea – £7bn imports (£6bn goods, £1bn services); £10bn exports (£6bn goods, £4bn services)

Other countries in Asia-Pacific – £13bn imports (£8bn goods, £5bn services); £11bn exports (£4bn goods, £7bn services)

Europe

EU – £451bn imports (£318bn goods, £133bn services); £356bn exports (£186bn goods, £170bn services)

EFTA – £50bn imports (£37bn goods, £13bn service); £40bn exports (£17bn goods, £23bn services)

Other European countries – £3bn imports (£1bn goods, £2bn services); £4bn exports (£3bn goods, £1bn services)

Rest of the world

Turkey – £16bn imports (£11bn goods, £5bn services); £10bn exports (£7bn goods, £3bn services)

UAE – £8bn imports (£3bn goods, £5bn services); £13bn exports (£7bn goods, £6bn services)

Saudi Arabia – £4bn imports (£3bn goods, £1bn services); £13bn exports (£5bn goods, £8bn services)

South Africa – £6bn imports (£4bn goods, £2bn services); £4bn exports (£2bn goods, £2bn services)

UK dependencies – £10bn imports (£1bn goods, £9bn services); £21bn exports (£1bn goods, £20bn services)

Everywhere else – £31bn imports (£20bn goods, £11bn services), £39bn (£18bn goods, £21bn services)