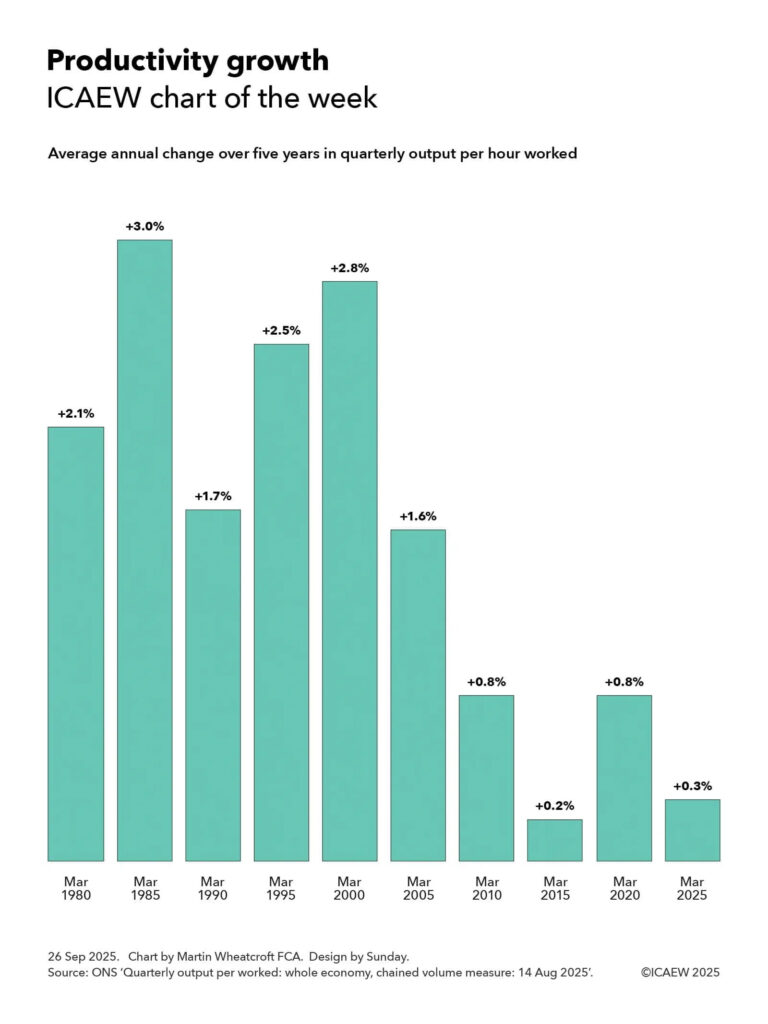

My chart for ICAEW this week looks at how productivity growth has slowed significantly over the past quarter of a century and asks what can be done to turn it around.

One of the biggest challenges facing the UK economy is the decline in productivity growth over the past quarter of a century as illustrated by my chart of the week for ICAEW. This shows how the average annual change over five years in quarterly output per hours worked in March 1980 was the equivalent of 2.1% a year higher than it was in the quarter to March 1975, five years earlier.

The chart also shows how output per hour rose by an annual average of 3.0% a year to March 1985, 1.7% to March 1990, 2.5% to March 1995, and 2.8% to March 2000.

Unfortunately, productivity growth has declined since then with quarterly output per hour increasing by an average of 1.6% a year over the five years to March 2005, 0.8% to March 2010, 0.2% to March 2015, 0.8% to March 2020 and 0.3% to March 2025.

These percentages go a long way to summarising how the UK economy has stalled since the start of the century, especially from the start of the financial crisis in 2007 through the austerity years, Brexit, the pandemic and the energy and cost-of-living crisis. We are producing less value per hour worked even as the population has grown and technology has further advanced.

While the crises we have gone through may partly explain some of the reduction in historical productivity growth over the last quarter of a century, the big question worrying many economists is why productivity has not returned to anywhere close to the levels seen before the turn of the century, or to even to those seen in the USA where, until recently, productivity growth has continued to hold up despite everything.

The Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR) most recent economic and fiscal forecast published in March 2025 was based on a central assumption of productivity growth averaging around 1.0% a year over five years to March 2030, significantly lower than the levels seen in the last century. There have been suggestions that the OBR intends to reduce this assumption when it updates its forecasts for the Autumn Budget 2025 in November, adding to the Chancellor’s headaches when she arrives at the despatch box.

One reason for the much lower levels of productivity growth this century may be the demographic change that has resulted in a much higher proportion of the population in retirement and a much older workforce on average. Another may be a question about whether the advent of the smart phone and ‘always on’ connectivity to the office has actually hindered rather than helped people be productive. A further reason could be the increasingly dire state of the public finances with debt rising from less than 35% of GDP in March 2005 to close to 95% of GDP, hampering the government’s ability to deliver the public services we need to thrive, in addition to raising the tax burden to historically high levels.

However, many of the reasons are likely to be driven by the challenges identified by ICAEW’s business growth campaign. This has identified how it has become increasingly too uncertain, too difficult, and too expensive to do business in the UK and calls for fundamental reform of tax, regulation and economic policy to support stronger business growth going forward.

Read more in ICAEW’s recommendations on how we can tackle the barriers to improving productivity in ICAEW’s business growth campaign.