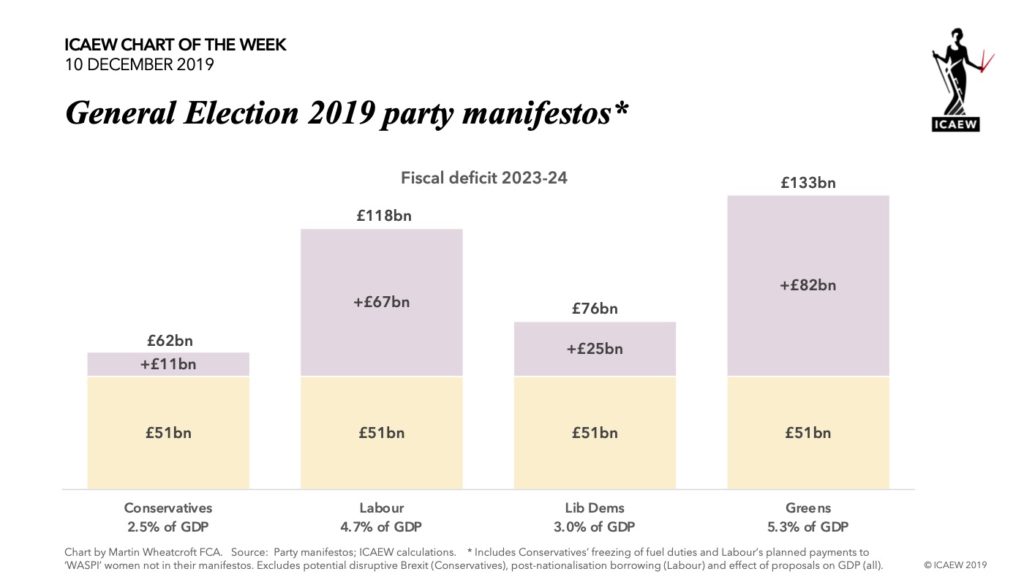

With voters in the UK going to the polls tomorrow, the #icaewchartoftheweek is on the political party’s plans for the public finances.

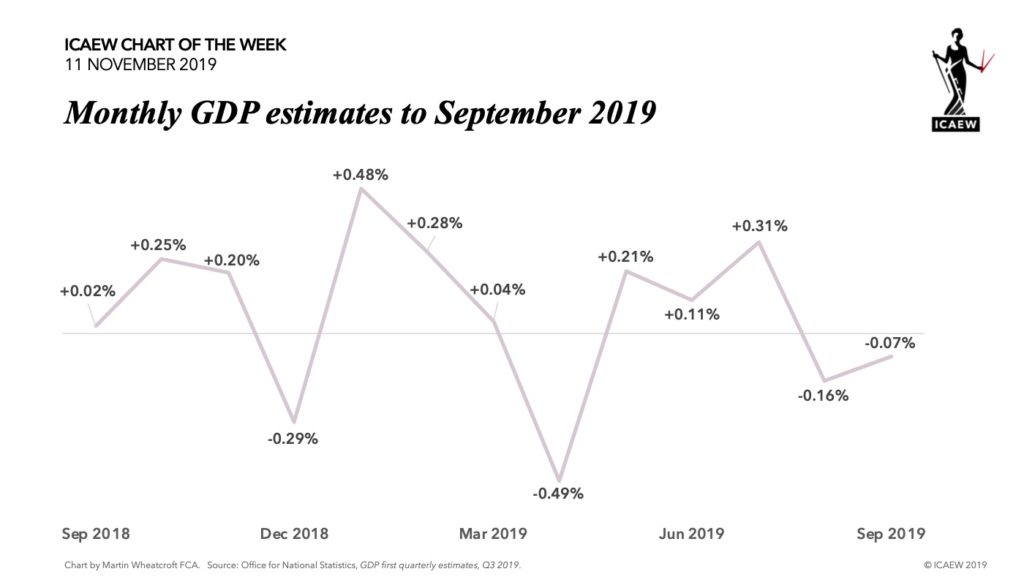

All the political parties are promising to increase taxes, public spending and investment, with the plan to eliminate the fiscal deficit now well and truly abandoned.

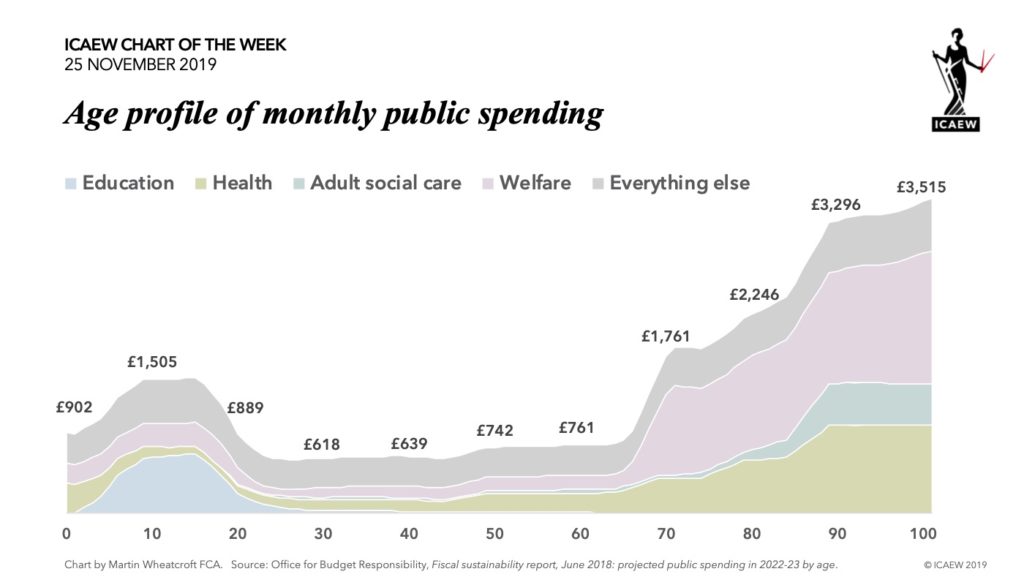

The Conservatives are promising the least in terms of additional spending and investment, with £3bn a year extra spending in 2023-24, £8bn in extra capital investment and tax rises broadly offsetting tax cuts. However, this is unlikely to be the final result as they have deferred significant financial decisions, such as the funding of adult social care, until after the election.

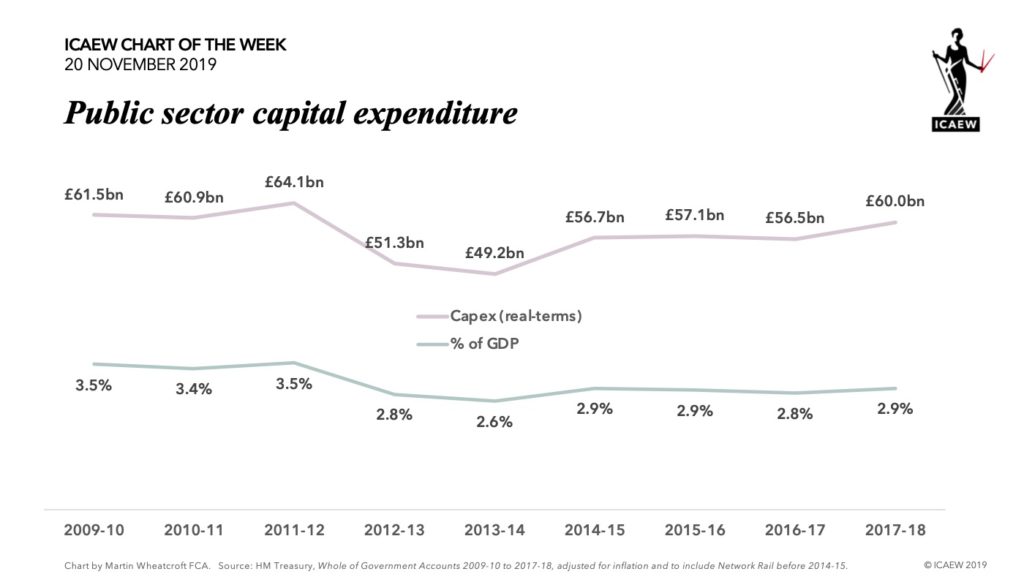

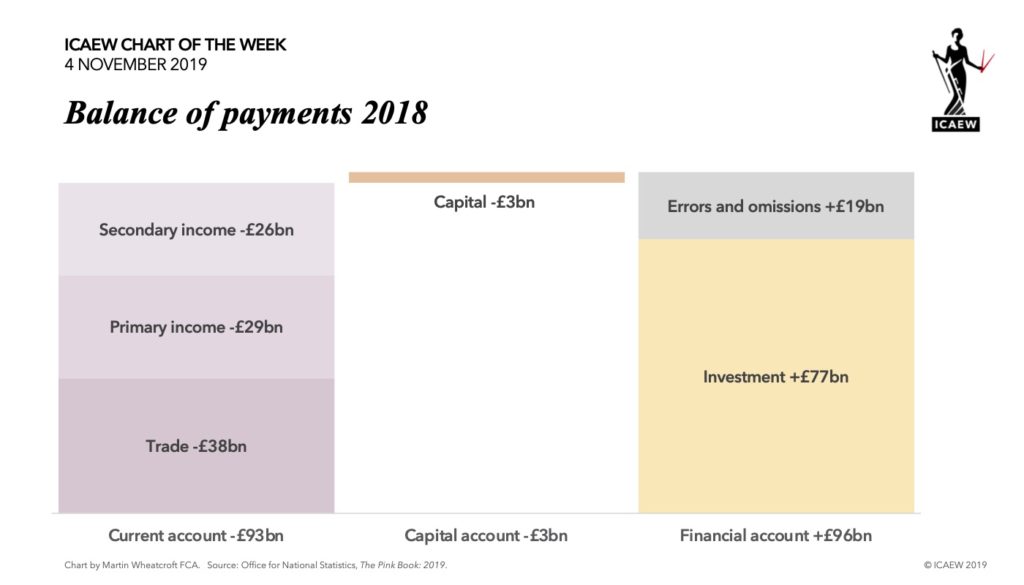

Labour is planning to spending much more with £83bn a year more spending by 2023-24, funded by £78bn tax increases and £5bn from higher economic growth. They plan capital investment of £55bn a year and £58bn in total over five years to compensate ‘WASPI’ women. This is pretty ambitious, leading the IFS and others to cast doubt on the achievability of their plans, while these numbers don’t include the additional borrowing from their plans to nationalise utilities, nor the borrowing of those businesses post-nationalisation.

The Lib Dem plans are also very ambitious, with £50bn extra a year public spending by 2024-25 funded by £37bn in higher taxes and £14bn in higher economic growth from cancelling Brexit. They plan to borrow an extra £25bn a year to fund new capital investment.

The Greens’ are planning to be even more ambitious, including completely reforming welfare provision with the introduction of a universal basic income, contributing to a £124bn increase in taxes and public spending (albeit some of this is a switch from tax deductions to cash payments). Their capital investment plans are the largest and likely to most difficult to deliver of all the major parties at £82bn a year on average over 10 years.

Unfortunately, none of the major political parties appear to have a fiscal strategy that extends beyond the next five years, with only limited measures to address the big financial challenges of more people living longer. This is disappointing given that relatively small actions taken now could make a big difference to the financial position of the nation in 25 years’ time.

ICAEW’s full analysis of the party manifestos can be found at icaew.com/ge2019manifestoanalysis.

You can be part of the conversation as part of ICAEW’s GE 2019: It’s More Than a Vote campaign.