8 June 2020: An NAO report has recommended that public bodies start preparations seven years before PFI contracts expire to negotiate the handover of assets and ensure service delivery is not disrupted.

The National Audit Office (NAO) has issued a report on the challenges public bodies are facing as private finance initiative (PFI) contracts come to an end.

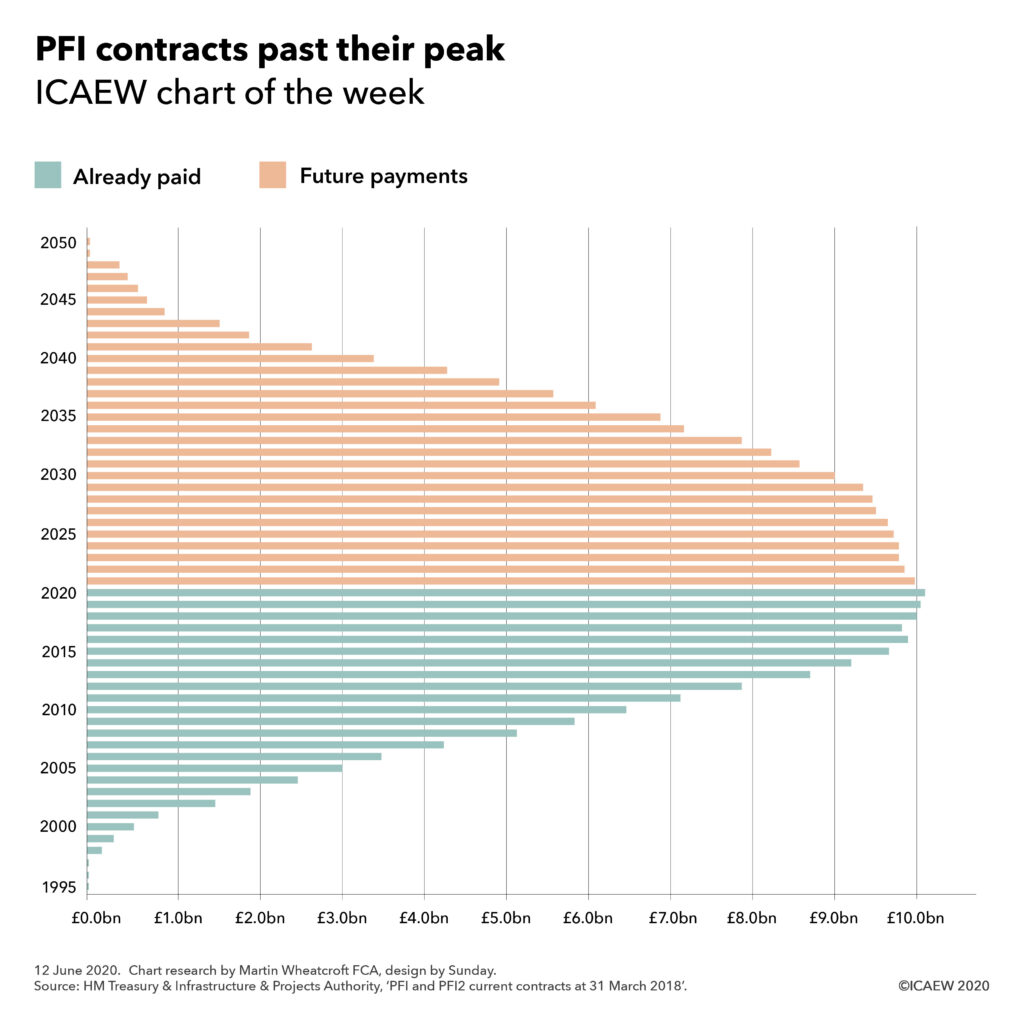

There are over 700 PFI contracts in the UK involving assets with a capital value of £57bn. Of these, 72 are due to expire over the next seven years in England, with an estimated £3.9bn of assets expected to revert to public sector ownership in that time.

The NAO is the independent audit body responsible for scrutinising public spending on behalf of Parliament. In addition to auditing the financial accounts of departments and other public bodies, the NAO examines and reports on the value for money of how public money has been spent.

PFI is a contracting approach where public bodies acquire the right to use an asset embedded within a long-term service contract. PFI contracts are typically for periods of up to 25 years and were used extensively from the late 1990s until the early 2010s to build a range of assets including (but not limited to) schools, hospitals, offices, transport infrastructure and military equipment.

Most PFI contracts expire from 2025 onwards, meaning there has so far only been a limited number of practical examples to learn from. Of those, the NAO reports that four out nine of the public bodies they surveyed were dissatisfied with the condition of PFI assets at expiry.

Key findings in the report include:

- The public sector does not have a strategic or consistent approach to PFI contract expiry and risks failing to secure value for money in negotiations with the private sector

- There is a risk of increased costs and service disruptions if public bodies do not prepare for contract expiry adequately in advance

- Insufficient knowledge about asset condition risks them being returned in worse quality than expected

- Contract expiry is resource-intensive and requires different skills, with external consultants needed in most cases

- Many public bodies start preparing four years or more before expiry, but experience suggests that preparation time is often underestimated. Infrastructure & Projects Authority (IPA) guidance is seven years

- There is a potential for disputes, especially as PFI providers often have a financial incentive to cut spending on asset maintenance and rectification towards the end of a contract

- Early PFI contracts are likely to be ambiguous about roles and responsibilities at contract expiry, with poorly drafted clauses open to interpretation.

The NAO recommends that public bodies and sponsor departments start preparing for contract expiry on a timely basis, ensure the PFI contract is complete and expiry provisions are well understood, develop a contract expiry plan and escalate problems which cannot be resolved at a local level. It also recommends that adequate funding is provided to cover dispute resolution and hiring additional resources.

The NAO believes that the IPA and sponsor departments have key roles to play in supporting public bodies and departmental teams responsible for PFI contracts with resources, sector-specific expertise, specialist advice and training. They need to identify high-risk contracts, such as those sitting with public bodies that lack appropriate skills and capabilities, and potentially establish an electronic repository to enable a more consistent approach across government.

The NAO says the IPA should assess the value of money of establishing a centralised pool of internal resources, such as lawyers and surveyors, that authorities can use, provide contract expiry guidance and terms of reference for consultants, develop a consistent approach to resolving legal disputes, and develop an investor strategy to manage relationships with PFI equity investors, management service companies, and contractors.

The report’s final recommendation is to HM Treasury, saying it should provide funding to departments assisting financially constrained public bodies where it is value for money and practical to do so.

Commenting on the report Alison Ring, Director, Public Sector, at ICAEW said:

“Public bodies are very experienced in the operation of ongoing PFI contracts. But with most PFI contracts not due to finish until 2025 or later, they have much less experience of managing contract expiry.

The NAO is quite right to highlight the need to start planning well in advance and the need to invest in the very different skills and expertise required to negotiate the handover of assets to ensure service delivery is not disrupted.

The role of the Infrastructure & Projects Authority and sponsoring departments will also be critical in supporting the 182 public bodies responsible for just one PFI contract, and in ensuring that lessons learned are shared across the public sector.

With tens if not hundreds of millions of pounds at stake if public bodies get this wrong, it is extremely important that the Government is not penny wise and pound foolish by failing to invest in the sufficiently skilled resources that will be required to get the best value for money for the taxpayer as PFI contracts come to an end.”

This article was originally published by ICAEW.