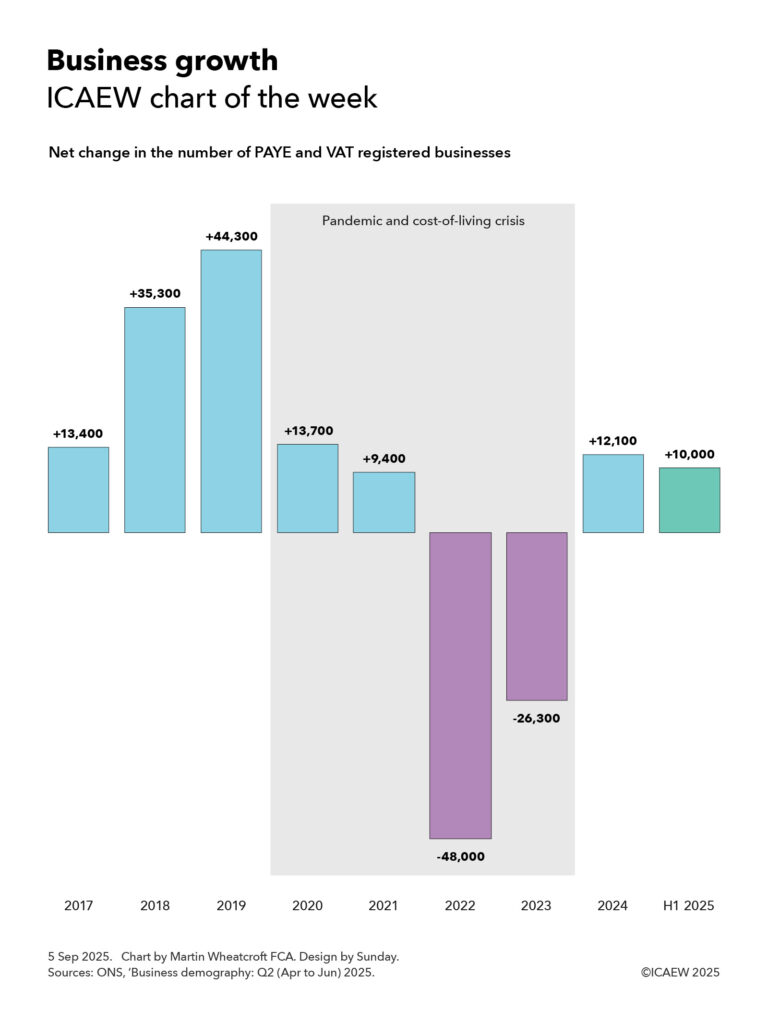

Our chart this week asks whether the recent low rate of growth in numbers of businesses registered for PAYE and VAT is linked to the increasing difficulty of doing business in the UK.

According to the Office for National Statistics, there were net additions of approximately 13,400, 35,300 and 44,300 to the UK inter-departmental business register in 2017, 2018 and 2019 respectively. This was followed by net additions of 13,700 and 9,400 in 2020 and 2021 during the pandemic and then net reductions of 48,000 and 26,300 in 2022 and 2023 during the cost-of-living crisis.

The register started growing again in 2024 with net additions of 12,100, followed by a net increase of approximately 10,000 in the first half of 2025. This rate of increase is significantly lower than the average rate of net business formation before the pandemic but is a significant improvement over the net contraction in the number of businesses in 2022 and 2023 during the cost-of-living crisis.

The net changes are equivalent to 0.5%, 1.3%, 1.6%, 0.5%, 0.3%, -1.7%, -1.0% and 0.4% in the total number of registered businesses in 2017 to 2024 respectively and annualised growth of 0.7% in the first half of 2025.

The total number of PAYE and VAT registered businesses is projected to have reached around 2.75m in June 2025, based on the last published count for March 2024 plus reported movements since then. This is out of an overall total of somewhere in the region of 5.5m businesses in the UK, with the difference mainly due to single-person companies and sole traders that do not employ any staff and operate below the VAT threshold of £90,000 per year.

The approximately 2.75m registered businesses can be analysed into just under 2.1m companies and other types of corporations, approximately 400,000 sole proprietors, 150,000 or so partnerships, and around 100,000 non-profit bodies, mutual associations and public sector organisations. Approximately 945,000 registered businesses are in London and the South East, 675,000 are in the Midlands and the East of England, 535,000 in the North of England, 340,000 in the South West of England and Wales, 175,000 in Scotland, and 80,000 in Northern Ireland.

Business births between 2017 and 2024 were approximately: 338,700; 341,100; 355,700; 322,000; 354,300; 327,500; 307,100; and 310,100; there were 167,600 in the first half of 2025. Business deaths in 2017 to 2024 were: 325,300; 304,800; 311,400; 308,300; 344,900; 375,500; 333,400; and 298,000; with 157,600 in the first half of 2025.

The overall change in the total number of registered businesses between 2017 and the first half of 2025 was 63,900, an average of 7,500 or 0.3% a year over eight and a half years, comprising an annual average of 332,100 business births less 324,600 business deaths in that time.

The chart highlights both the very difficult economic times we have been through in the past few years with the pandemic and cost-of-living crisis and the current period of weak economic growth that has yet to return to pre-pandemic levels.

One of the key ways that we can increase the rate of net business formation is to make it easier to do business in the UK, as discussed in ICAEW’s growth campaign. This asks why it is too difficult, too expensive and too uncertain to do business in the UK today and suggests ways the government can streamline regulation, reduce costs and unnecessary frictions, and provide businesses with greater confidence to invest and grow.