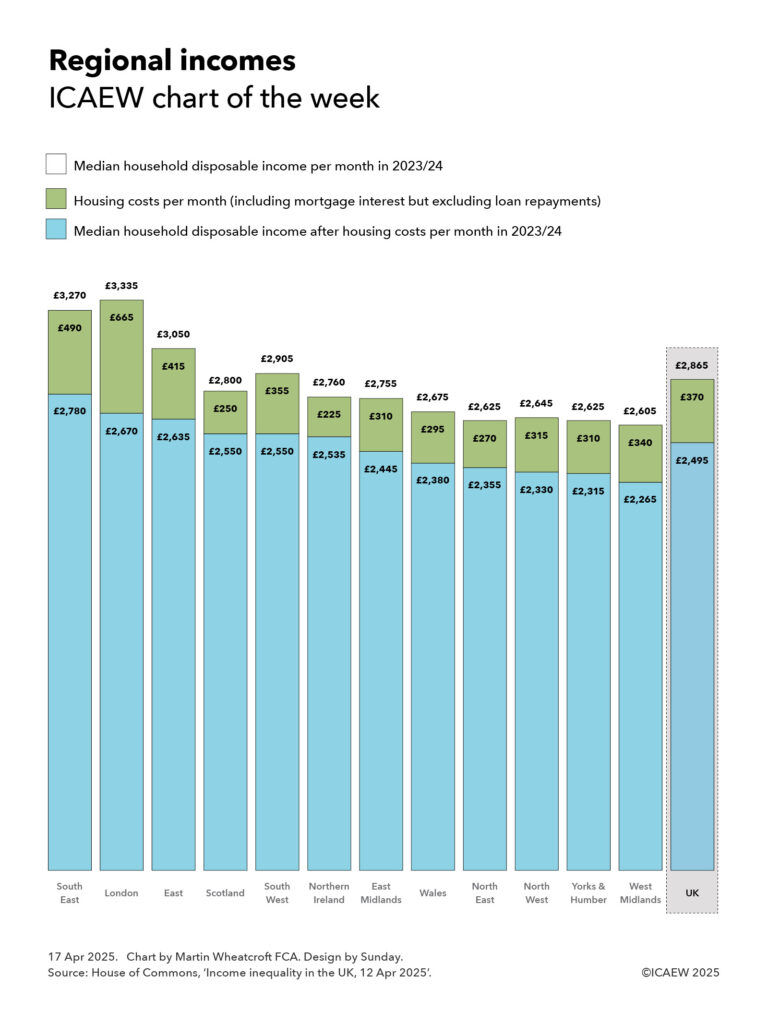

Our chart this week looks at how median household disposable income varies across the UK, with the South East region topping the rankings and the West Midlands region at the bottom.

Our chart this week is adapted from one of the charts in a House of Commons research report on income inequality in the UKpublished on 12 April 2025, showing how median household disposable incomes before and after housing costs vary significantly between the regions and nations of the UK.

As the chart illustrates, median household disposable income in the South East of England during 2023/24 was the highest in the UK at £2,780 per month, reflecting a median disposable income of £3,270 per month, before housing costs of £490 per month.

London had a higher median disposable income at £3,335 per month, but also much higher housing costs at £665 per month, resulting in a lower median disposable income after housing costs of £2,670 per month.

This is followed by the East of England, with median disposable income after housing costs in 2023/24 of £2,635 per month (£3,050-£415), Scotland £2,550 (£2,800-£250); South West £2,550 (£2,905-£355); Northern Ireland £2,535 (£2,760-£225); East Midlands £2,445 (£2,755-£310), Wales £2,380 (£2,675-£295); North East £2,335 (£2,625-£270); North West £2,330 (£2,645-£315); Yorkshire and the Humber £2,315 (£2,625-£310); and West Midlands £2,265 (£2,605-£340).

Median household disposable income after housing costs in the West Midlands is 19% less than in the South East of England. West Midlands in this case includes Herefordshire, Shropshire, Staffordshire, Warwickshire and Worcestershire, in addition to the West Midlands ‘city-region’ that is centred on Birmingham.

The median household disposable income after housing costs for the UK is £2,495 per month (£2,865-£370) or £574 per week (£659-£85).

The chart doesn’t show the median for England, which is also £2,495 per month but reflects a higher median disposable income and higher housing costs (£2,885-£390).

For this purpose, household disposable income is equal to income from employment and investments plus cash benefits (state pension, universal credit and other welfare benefits) net of income tax, national insurance, council tax (domestic rates in Northern Ireland), pension contributions, and student loan repayments, among other items. It is not net of VAT or other indirect taxes that households also pay.

Household disposable income is not the same as discretionary or surplus income, as it is before deducting other costs that families need to incur, such as food, energy, clothing, internet and childcare provision to name just a few examples.

Housing costs include rents (gross of housing benefit), water bills, mortgage interest payments, structural insurance premiums, ground rent and service charges. They exclude the repayment element of mortgage payments, meaning that disposable income after housing costs on a cash basis can be substantially lower than is suggested by the chart.

In addition, as the median household for disposable income before housing costs is different to the median household for disposable income after housing costs, the housing cost numbers in the chart are affected by the much lower costs incurred by most pensioner households, the majority of which have paid off their mortgages and so live rent-free.

Disposable incomes vary widely between households with the bottom and top 10% of households in the UK having a monthly disposable income before housing costs in 2023/24 of less than £1,300 per month or more than £5,475 per month respectively.

Disposable income also varies between household types, with (for example) a UK median household disposable income before housing costs in 2023/24 of £4,320 per month for a couple with two children under the age of 14, £3,385 per month for a single person with two children under the age of 14, £2,825 per month for a couple with no children, and £1,890 per month for a single person with no children.

While the variations between households means there are some very well-off households as well as very poor ones in each region, the median numbers do tell us a lot about the relative prosperity of each region, with London and the South East being significantly more prosperous compared with Wales, the three Northern regions of England, and the West Midlands.