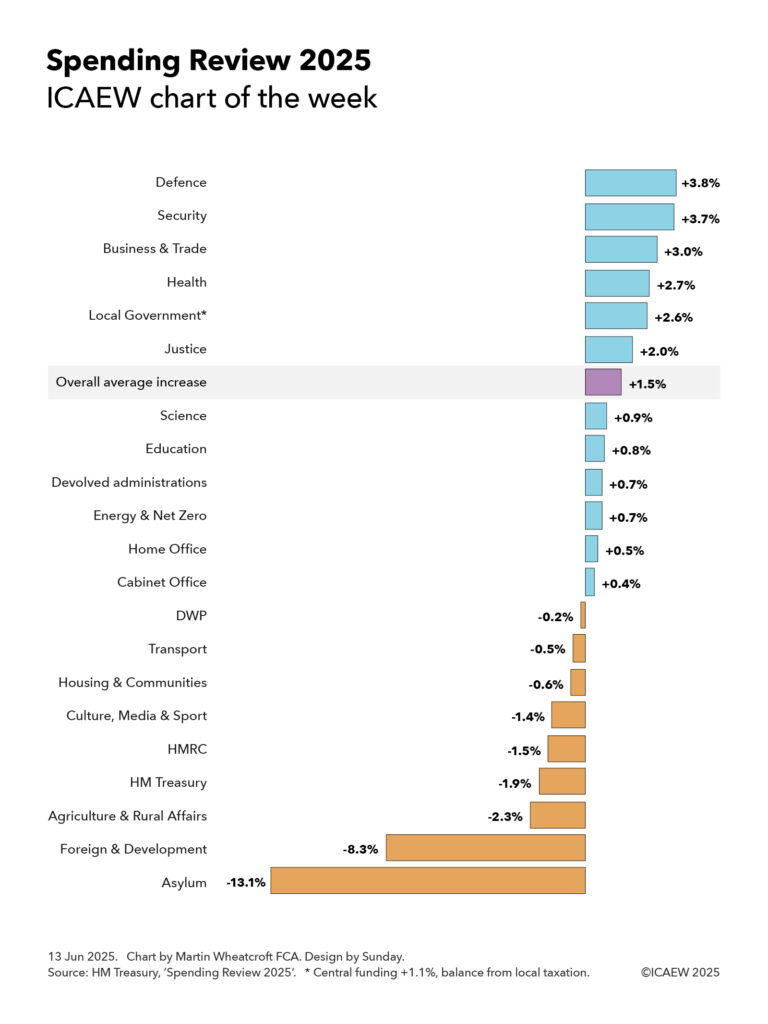

My chart for ICAEW this week looks at the government’s priorities as expressed through departmental budgetary allocations over the next three years.

The Spending Review 2025 establishes base operating budgets for government departments for the three financial years from 1 April 2026 (2026/27, 2027/28 and 2028/29) and base capital budgets for four financial years (extending to 2029/30).

Departmental budgets for the current financial year ending on 31 March 2026 (2025/26), total £648bn and are expected to rise to £678bn in 2026/27, £697bn in 2027/28, and £717bn in 2028/29, an increase of 10.6% over the three years or 3.4% a year. This is equivalent to an average increase of 1.5% a year in real terms after adjusting for inflation of 1.9% a year on average over the spending review period.

The totals can be analysed between operating or ‘day-to-day’ budgets of £517bn, £536bn, £552bn and £568bn in 2025/26, 2026/27, 2027/28 and 2028/29 respectively and capital budgets of £131bn, £143bn, £145bn and £149bn. These are real terms increases of 1.2% and 2.4% a year on average over three years.

The capital budget in 2029/30 is £152bn, a cut in real terms that reduces the average annual increase in capital budgets over four years to 1.8% a year on average.

My chart this week highlights how the 1.5% average annual real increase over three years in total budgets (operating and capital) has been allocated across departments, starting with the Ministry of Defence, which leads the pack with an average increase in its budget of 3.8% a year, followed closely by the security services, with an average annual increase of 3.7%. This reflects the elevation of national defence and security to the top of the government’s priorities since the general election last year, even though this increase will only move defence and security spending from 2.3% of GDP currently to 2.6% of GDP by 2027, a long way off the proposed 3.5% of GDP new minimum to be discussed at the NATO summit.

Economic growth and the NHS are the next highest priorities for the government and so it is perhaps unsurprising that the Department of Business & Trade does well with an annual average increase of 3.0%, closely followed by the Department of Health & Social Care, which receives 2.7%. The latter is the biggest increase in cash terms, at £31bn in total or about £12bn more in 2028/29 after adjusting for inflation.

Local government finances are in a parlous state and so the government has pencilled in a 2.6% average annual increase in core budgets for local authorities in England over the next three years. However, it is only increasing central funding by 1.1% a year on average, implying the balance will need to be made by local taxation, principally council tax.

The Ministry of Justice has been awarded 2.0% a year on average as the government seeks to tackle significant backlogs in the courts, overcrowded prisons and significantly under-resourced probation services.

The Department of Science, Innovation and Technology has received a below average annual increase of 0.9% over the next three years, but this follows an almost 12% increase over the past two years as the government has sought to increase investment in research and development to boost economic growth.

Despite being a key priority for the government, the Department for Education has only received a 0.8% average annual increase, partly because of falling primary school rolls in line with a significant fall in the birth rate over the last decade.

The devolved administrations – Scotland (0.8%), Wales (0.7%) and Northern Ireland (0.5%) – are budgeted to receive an average of 0.7% a year over three years as a consequence of the Barnett formula that links UK national government spending in England to the block grants provided to each devolved administration, adjusted for relative changes in population among other factors.

The Department for Energy Security and Net Zero is budgeted to receive 0.7% on average over three years, although this translates into an average annual increase of 2.7% a year once the UK government’s one-off (but long running) investment in the Sizewell C nuclear power plant is excluded. The latter peaks in the spending review period, but then starts to fall.

The Home Office is scheduled to receive a below average increase of 0.5% a year, although the government notes that core police operating budgets should go up by 1.7% once the contribution from local taxation is factored in. This increase also excludes spending on asylum seekers, a big item within the Home Office budget that is expected to fall by a real term average of 13.1% a year over three years as the backlog in asylum claims is tackled and lower cost alternatives to housing claimants in hotels are found.

The Cabinet Office is expected to receive just 0.4% on average reflecting the contribution that planned efficiency savings are expected to contribute to administrative budgets. This is also the reason for the 0.2% a year real-terms fall in the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) budget as automation helps reduce the cost of administering the welfare system.

The budget of the Department for Transport is expected to fall by 0.5% a year overall, but this partly reflects a fall in spending on High Speed 2 as it comes closer to completion. If that is excluded, the department’s budget is expected to increase by 0.5% a year on average. The actual increase in spending should be even higher, as the budget is net of passenger revenues that are expected to grow at a faster rate over the next three years.

Extra money for housing was found within the spending review, but this wasn’t enough to stop the budget for the Department of Housing, Communities and Local Government from shrinking by an annual average of 0.6% a year as other activities are cut back, while the Department for Culture, Media & Sport (-1.4% a year on average) has also been asked to cut back its activities.

HMRC (-1.5% a year) and HM Treasury (-1.9% a year) see their budgets reduced significantly, with digitisation and efficiency savings expected to contribute significant sums.

The Department for Farming, Agriculture, and Rural Affairs (-2.3%) is also expected to see significant cuts over the next three years, as is the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (-8.3%), although in the latter case that is principally driven by the decision to reduce overseas development assistance from 0.5% of GDP to 0.3% of GDP although some will come from back office savings.

Not shown in the chart are small and independent bodies and the government legal function, which are together expected to increase by 0.4% a year on average, although this comprise a -0.5% annual reduction in the former and a 5.3% average annual increase in the latter. The net changes after inflation are a fall of less than £0.1bn and an increase of just over £0.1bn respectively, which are rounding errors in the hundreds and hundreds of billions of pounds spent by government departments each year.

Reading the Spending Review 2025 is a good way of understanding the current government’s priorities expressed in financial terms. A lot more money for defence and the NHS, substantial sums for business and the justice system, and significant cuts in international development, asylum handling, agriculture and administration costs. There’s some money for transport and housing, but that’s offset by savings from HS2 and other activities.