My chart for ICAEW this week looks at the impact on the US federal government deficit of the major tax and spending changes passed by Congress and signed into law by President Trump on 4 July 2025.

My chart this week looks at the impact on the US federal government deficit of the major tax and spending changes passed by Congress and signed into law by President Trump on 4 July 2025.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) published on 21 July 2025 its assessment of Public Law 119-21 (the 21st law passed by Congress in its 119th session), also known as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act 2025 (OBBBA).

OBBBA was passed by Congress and signed into law by President Trump on 4 July 2025 and contains sweeping changes to the US federal tax system as well as a significant shift in spending priorities.

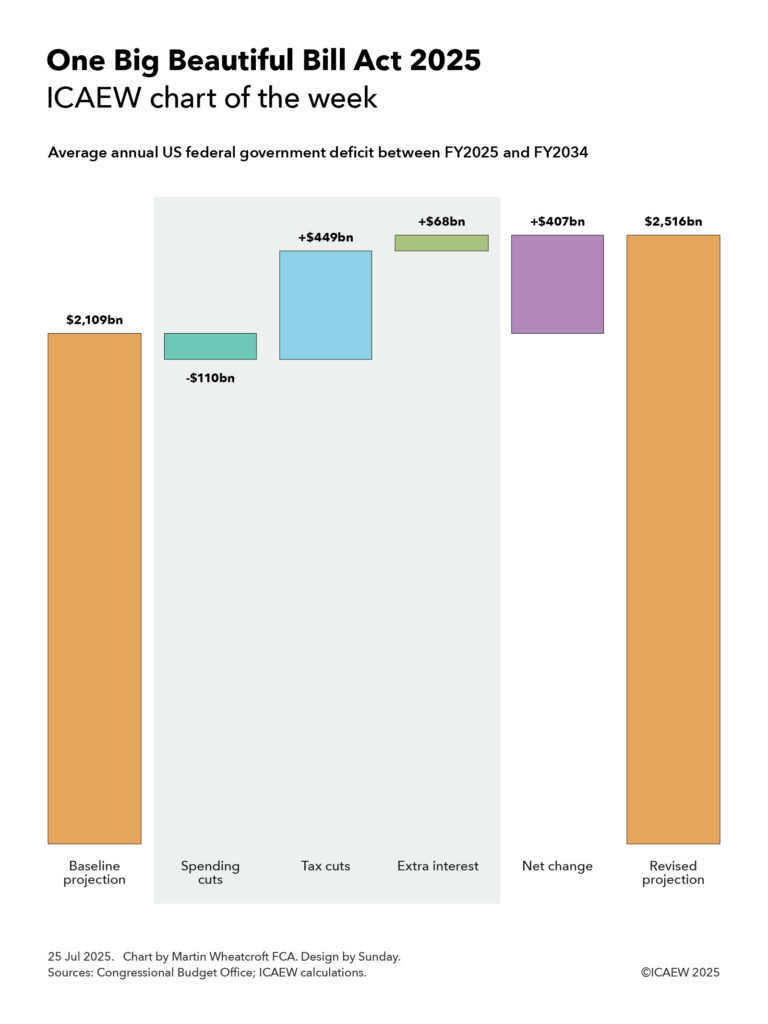

The chart this week attempts to illustrate the impact of OBBBA on the federal deficit by looking at how it changes the average annual projected deficit over the next 10 years from FY2025 (the current fiscal year ending on 30 September 2025) to FY2034, compared with the CBO’s baseline projection.

The baseline projection, published by the CBO in January 2025, was for the federal government deficit to increase from $1,865bn in FY2025 to $2,597bn in FY2034, an average deficit over the 10 years of $2,109bn or 5.8% of GDP.

According to the CBO, OBBBA is expected to increase the federal deficit each year by $339bn on average over the period to FY2034, with a net cut in federal spending of $110bn on average offsetting a net cut in revenues of $449bn. The CBO’s assessment does not take account of the additional cost of financing these higher deficits, which ICAEW calculates would add a further $68bn a year on average to the interest bill.

The consequence is a net increase in the annual federal deficit of $407bn on average over 10 years, taking it to an average of $2,516bn or 7.0% of GDP.

Net spending cuts of $110bn comprise spending increases of $66bn a year on average, net of spending reductions of $164bn a year and incremental ancillary income that is deducted from spending of $12bn. Extra spending includes an extension of child tax benefits ($19bn a year on average) and more money for homeland security and immigration enforcement ($18bn), the military and coastguard ($17bn), farm subsidies ($5bn), air traffic control ($1bn), the mission to Mars ($1bn) and other items ($5bn).

Spending reductions include cuts in Medicaid and Medicare programmes ($106bn on average each year), education and student loan relief ($30bn), other welfare and health programmes ($19bn), clean energy subsidies ($8bn) and other cuts ($1bn), while ancillary income comprises $9bn on average from spectrum auctions, $2bn from oil and gas leases, and $1bn extra from higher visa fees.

Net tax cuts comprise $511bn a year in tax cuts less $62bn a year in tax increases.

Tax cuts include making previous temporary tax cuts permanent ($379bn), business tax reforms ($97bn), personal tax reforms ($26bn), energy related tax credits ($4bn), Medicaid and Medicare related tax deductions ($3bn), and other ($2bn). Tax increases include the termination of tax reliefs for clean energy ($47bn a year), addressing tax loopholes ($6bn), additional immigration fees included in revenue ($4bn), taxing low-value international shipments ($4bn) and other ($1bn).

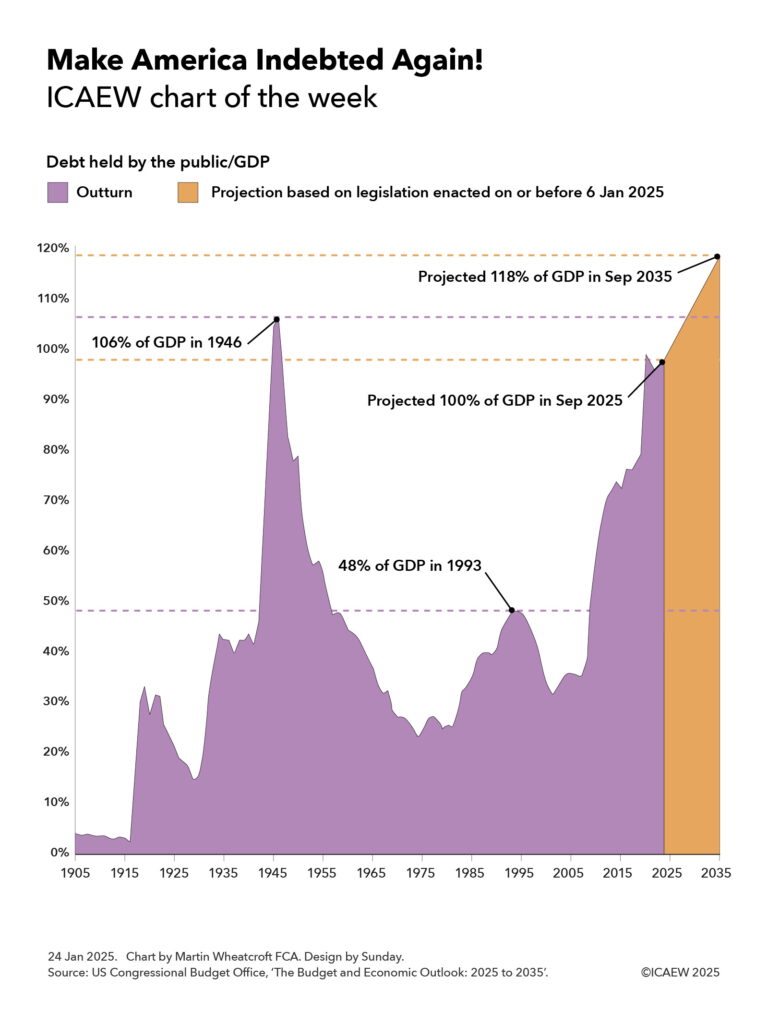

The CBO doesn’t directly conclude what this will mean for the US national debt (debt held by the public), which was expected in January’s baseline projection to increase from $28.2tn or 98% of GDP at the start of the current financial year to $49.5tn or 117% of GDP on 30 September 2034. Adding $4.1tn over 10 years to that amount suggests this would increase to $53.6bn or 127% of GDP.

These numbers don’t take account of the anticipated economic boost of lower taxes that should partially offset some of the tax impacts set out in the CBO’s analysis, as well as increasing the denominator in the deficit to GDP ratio. However, they also don’t take account of other factors such as US trade policy – including the additional tax receipts from tariffs and the potential effect that those higher taxes will have on the US economy – or many other policies of the US administration. We will need to wait for the CBO’s next full economic and fiscal projections later in the year to understand more about what that might mean.

Either way, the OBBBA will go down as one of the most consequential legislative acts of the US Congress in recent years.