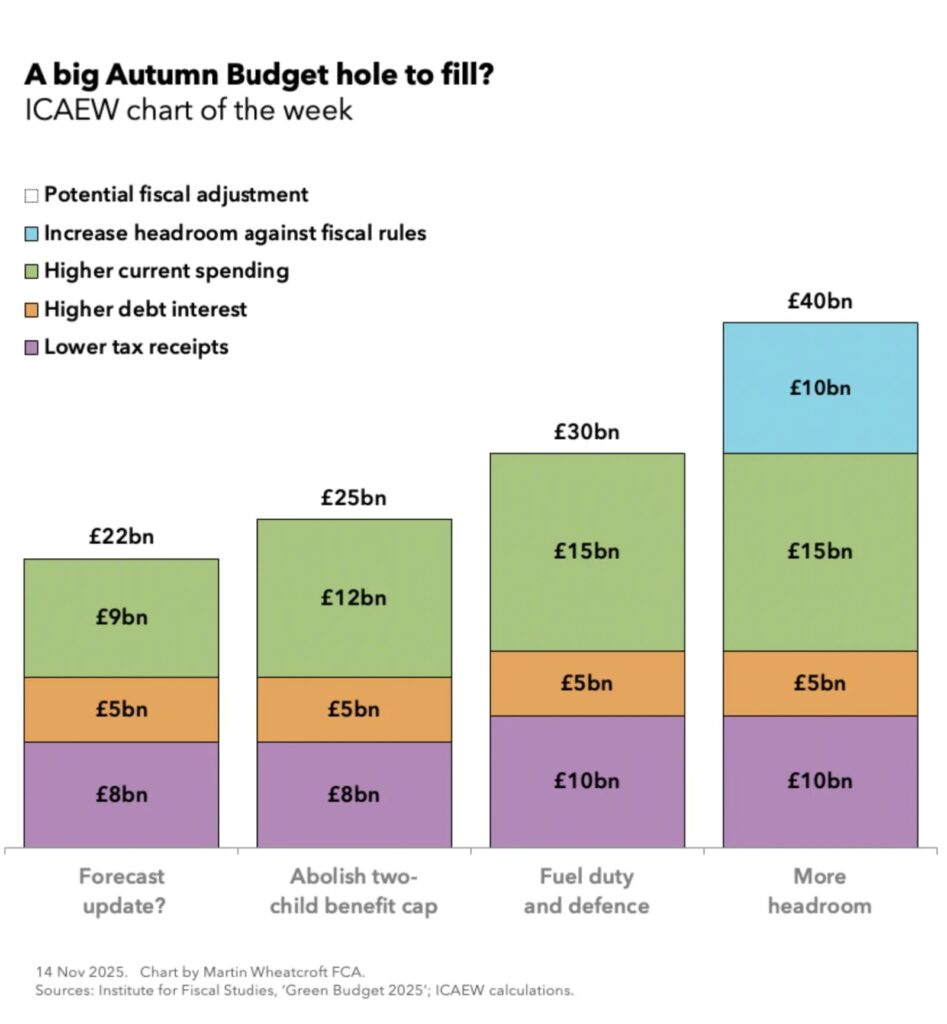

My chart for ICAEW this week takes a look at the £40bn ‘hole’ in the public finances that the Chancellor may have to fill when she presents the Autumn Budget 2025 to Parliament on Wednesday 26 November.

There are two really big questions that most of us have for the Chancellor about the Autumn Budget 2025. Firstly, just how much money does she need to find? Secondly, where is she is going to find it?

My chart for ICAEW this week focuses on the first question – how much will the Chancellor need to find (in tax rises or spending cuts) to stick within her fiscal rules?

Speculation ranges from just under £20bn a year up to as much as £50bn depending on who you talk to, with the consensus being somewhere in the region of £30bn or £40bn.

The starting point for the chart is the official OBR projection that the Chancellor has already received. As we don’t have access to that, we have cribbed from the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) Green Budget 2025 report, an independent ‘green paper’ pre-legislative report that provides an in-depth analysis of the economic and fiscal situation facing the UK that also takes a look at potential options available to the Chancellor.

Based on an updated economic forecast prepared by Barclays, the IFS think that the OBR’s March 2025 projected current budget surplus of £10bn in 2029/30 could be revised down to a projected current budget deficit of £12bn – a £22bn deterioration.

The numbers calculated by the IFS indicate £8bn lower tax receipts, £5bn higher debt interest, and £9bn higher current spending. The lower tax receipts and higher debt interest reflect a less favourable economic outlook than anticipated by the OBR back in March, while the latter consists of £1bn from the partial roll-back of cuts to the winter fuel allowance, £5bn from the failure to enact previously planned cuts to disability benefits, and £3bn from the effect of higher than previously forecast inflation on the uprating of the state pension and other welfare benefits.

If the OBR’s updated projections were to align with this scenario, then the Chancellor would need to find £22bn to get back to a projected current budget surplus of £10bn in 2029/30, assuming she decides again to give herself £10bn of headroom against her primary fiscal rule of a current budget balance.

We don’t know how these numbers compare with the numbers that the OBR are working on, but we do know that the OBR has been reviewing its assumptions for productivity growth, where it has proved consistently over-optimistic in previous forecasts. The IFS estimate that just a 0.1 percentage point downgrade in annual productivity growth would reduce the current budget balance by around £7bn in 2029/30, highlighting how sensitive the numbers are to relatively small changes. The IFS assume a downgrade of between 0.1 and 0.2 percentage points in their projection, although some rumours suggest the OBR has been considering a downgrade of as much as 0.3 percentage points.

The Chancellor has dropped a clear hint that she is going to abolish the two-child limit in the Autumn Budget as part of the government’s efforts to tackle child poverty, with the IFS and the Resolution Foundation both estimating that this could cost the exchequer between £3bn and £4bn a year by 2029/30. This would take the potential ‘hole’ up to £25bn.

For the purposes of the chart, I have also added in £5bn for further policy changes. Firstly, there is a good chance that the Chancellor will choose to make the existing 5p ‘temporary’ cut in fuel duties permanent at a cost of £2bn a year. This is currently scheduled to be reversed on 1 April 2026, alongside the expected end of the annual freeze in fuel duties – a measure that, if continued, could cost a further £3 billion a year by 2029/30.

The government is also under significant pressure – from President Trump and other NATO allies in particular – to accelerate increases in the defence budget to meet the new NATO target for spending on defence and security of 3.5% of GDP. Although the NATO target includes capital expenditure (which is not part of the current budget surplus or deficit), we have included a proxy amount of £3bn a year by 2029/30 for additional operating expenditure on defence.

This brings the potential funding requirement to roughly £30 billion, if the Chancellor aims to maintain £10bn of headroom against her fiscal rule of achieving a current budget balance in the fourth year of the forecast.

Unfortunately, as the government has discovered over the past year, such a small margin – less than 0.3% of GDP – is hugely problematic. Relatively small changes in the OBR’s assumptions or in actual economic performance can easily use up all the headroom, leading (as we have seen) to endless speculation about what the Chancellor is going to have to do to bring the public finances back under control.

The Chancellor is therefore expected to provide herself with a bigger cushion to reduce the risk of having to come back to raise taxes for a third time. The chart thinks she is likely to choose to double the level of headroom as a minimum – from £10bn to £20bn – with some economic commentators suggesting that an even larger cushion might be necessary.

The IFS point out in their report that extra headroom may be needed in any case because of the Chancellor’s second ‘debt’ fiscal rule, which is for public sector net financial liabilities to be falling as a share of GDP by the fourth year of the fiscal forecasts. Although she could cut the capital expenditure already budgeted for 2029/30 to remain within the fiscal rule, the Chancellor has said she wishes to avoid doing so.

Whatever happens, it looks like the Autumn Budget 2025 is going to be a pretty big deal.