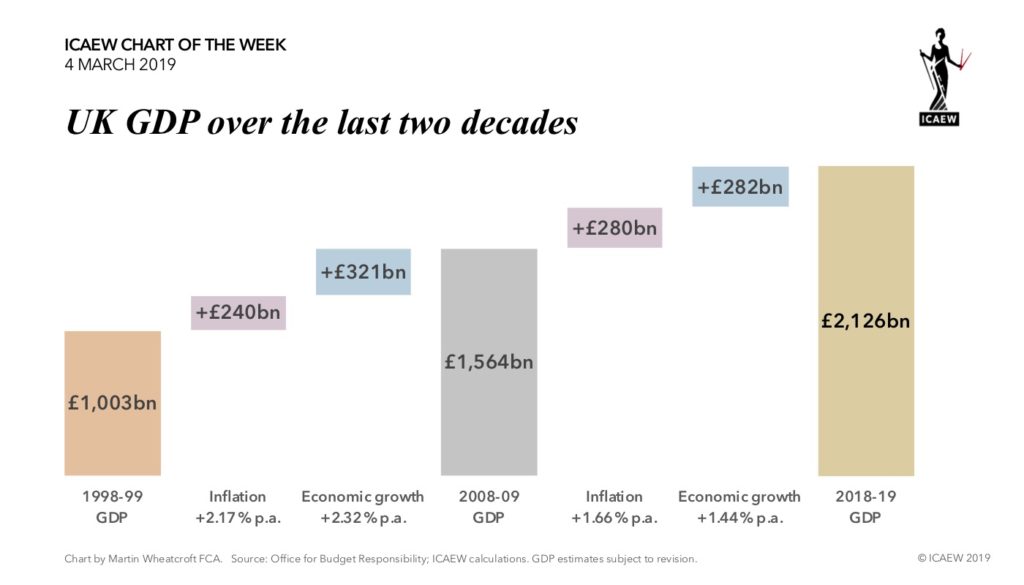

The ICAEW chart of the week this time is on the size of the UK economy over the last couple of decades.

According to the Office for Budget Responsibility, economic activity in the UK is forecast to add up to £2,126bn for the year ending 31 March 2019, an average increase of 3.1% a year over the £1,564bn reported a decade earlier.

Excluding inflation of 1.66% per annum, this means economic growth has averaged 1.44% over the last ten years since the financial crisis. This is significantly lower than economic growth in the decade before the the financial crisis of 2.32%, as well as the average of 2.45% seen in the 30 years up to 1998-99.

Some economists are suggesting that low rates of growth may be a ‘new normal’ and that we should not expect a return to previous levels. If so, there will be significant implications for how the government manages the public finances, with reduced future revenues available to fund growing public liabilities and financial commitments such as the state pension.

Another reason perhaps to re-evaluate the ‘pay-as-you-go’ assumption that underpins the government’s long-term strategy for the public finances?