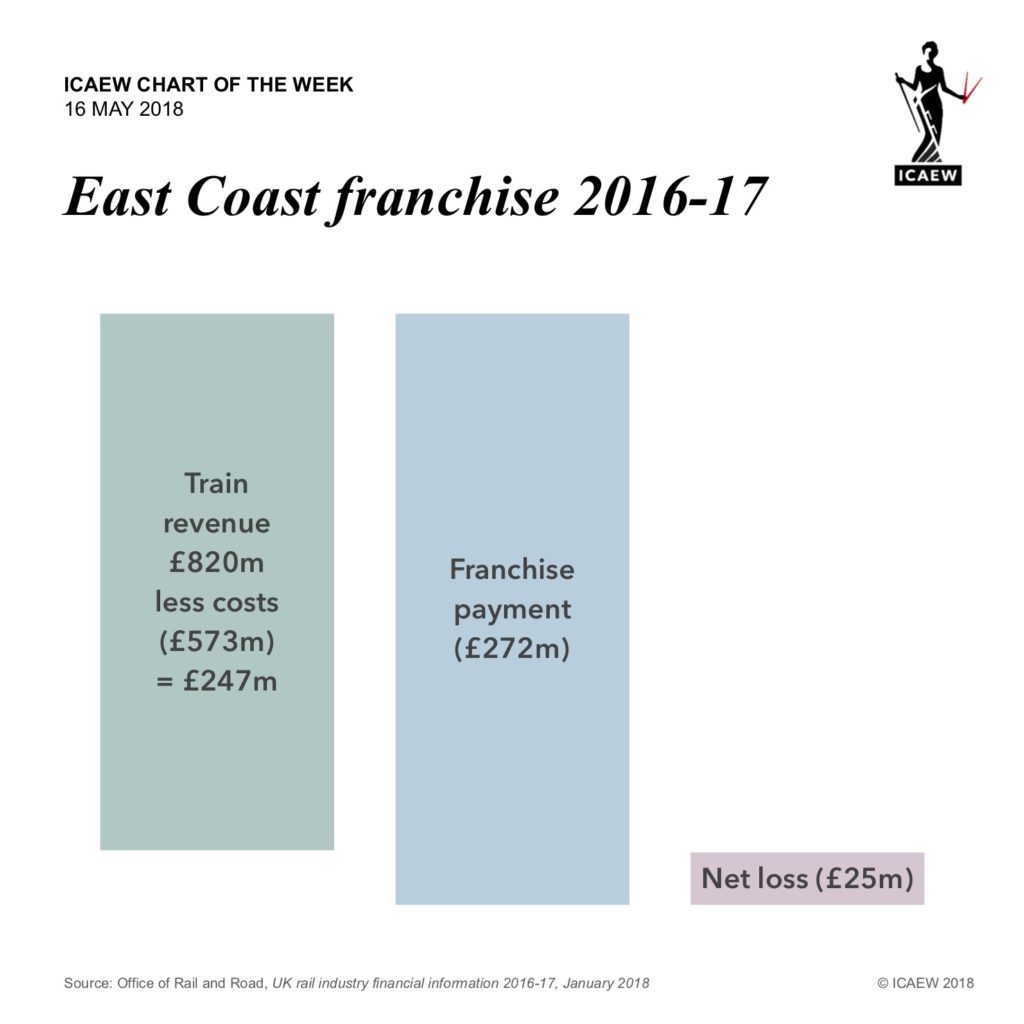

Our chart this week provides an insight into why Stagecoach and Virgin decided to ‘hand back the keys’.

The East Coast franchise generated £247m in 2016-17, before a franchise payment to the Department of Transport of £272m. A net loss of £25m. The losses were likely to grow in the future because the payment for the franchise was due to increase significantly over the new few years at the same time as revenues are stalling.

Franchise revenue of £820m in 2016-17 included £741m from passengers at an average fare of £34.23 per journey or 13p per km travelled, while direct costs of £573m comprised £158m in staff costs, £117m in track access charges, £93m for rolling stock, £22m on fuel, and £183m in other costs.

The problem for the government is that this is supposed to be one of the financially viable rail franchises. However, the government’s subsidies and losses on the East Coast routes were £289m in 2016-17, more than the £272m it received as a franchise payment from Stagecoach and Virgin. It really needs this particular franchise to generate more money than it does.

The challenge for government is whether it can make do and mend, or whether the entire franchising model needs to be revisited.