The news that investors are running out of German Bunds prompted us to take a look at government bonds for the #ICAEWchartoftheweek.

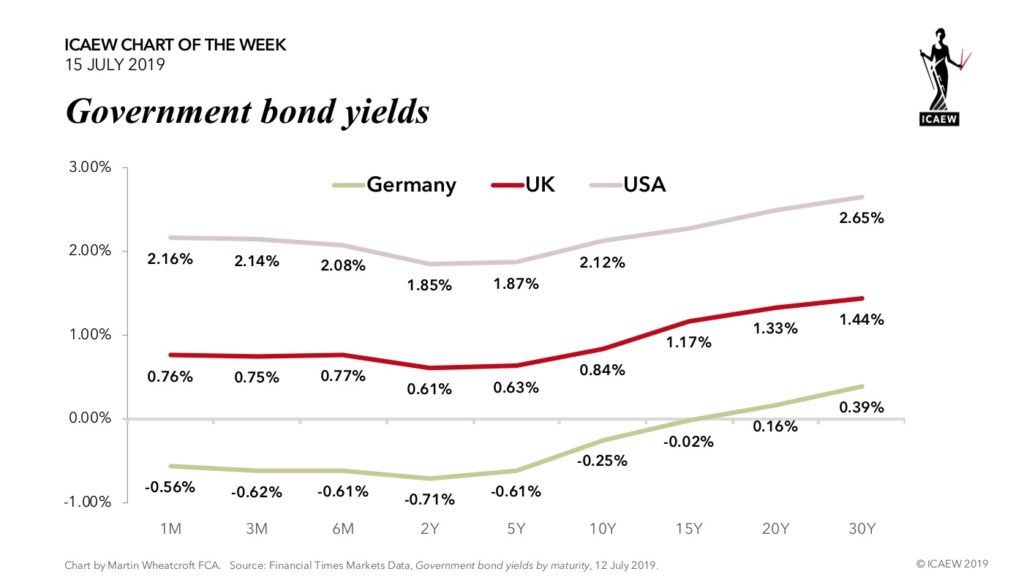

The shortage is so severe that investors are willing to pay an annualised rate of 0.71% for the privilege of owning a 2-year Schaetze, or 0.25% to own a 10-year Bund. Admittedly, you could earn a princely return of 0.39% a year if you chose to invest in 30-year Bunds, but that is a fair amount of time to tie up your money.

Of course, Germany is unusual in running a fiscal surplus and paying down debt each year (with €52bn repaid in 2018 for example), reducing the quantity of bonds available to investors. Most Western governments need to borrow more in order to pay their bills, such as Italy where the 1.70% yield on an Italian 10-year BTP is 195 basis points higher than its German equivalent.

Despite the progress the UK has made in reducing its deficit, it still needs to raise £30bn in 2019-20 – in addition to the £99bn it needs to fund the repayment of existing debts as they mature. The good news is that the 0.84% yield on a 10-year gilt (for example) is substantially lower than in previous eras, helping to gradually bring down the weighted average interest rate payable on the national debt as gilts issued when rates were higher are refinanced.

Yields are higher in the US, in the context of stronger economic growth than both the UK and Germany in the last few years. The annualised return of 2.12% available to those investing in a 10-year US Treasury bond is 237 basis points higher than on a German 10-year bond. This is still relatively cheap by historical standards, especially in the light of the $0.9tn the US federal government needs to borrow this year to fund its fiscal deficit, not including the refinancing of existing debt or the sales of bonds by the Fed as it unwinds QE.

Yield curves are usually upward sloping, with investors demanding (and governments willing to pay) higher yields on bonds with longer maturities. However, the curves for both Germany and the UK are ‘partially inverted’ with investors are willing to accept lower yields on 2-year or 5-year bonds than they will for short-term bills, while the US is ‘inverted’ with the 10-year yield lower than 1-month and 3-month yields, admittedly only by two or four basis points respectively.

Conventional wisdom is that a partially inverted yield curve presages lower economic growth and a fall in short-term interest rates, while a fully inverted curve may signal that a recession is on its way. But these are not normal times, with ultra-low interest rates and quantitative easing making it difficult to assess their predictive value, with some commentators suggesting that these inversions may just be temporary.

Either way, the era of cheap money looks likely to continue for longer than anyone expected; we really are living in interest-ing times.