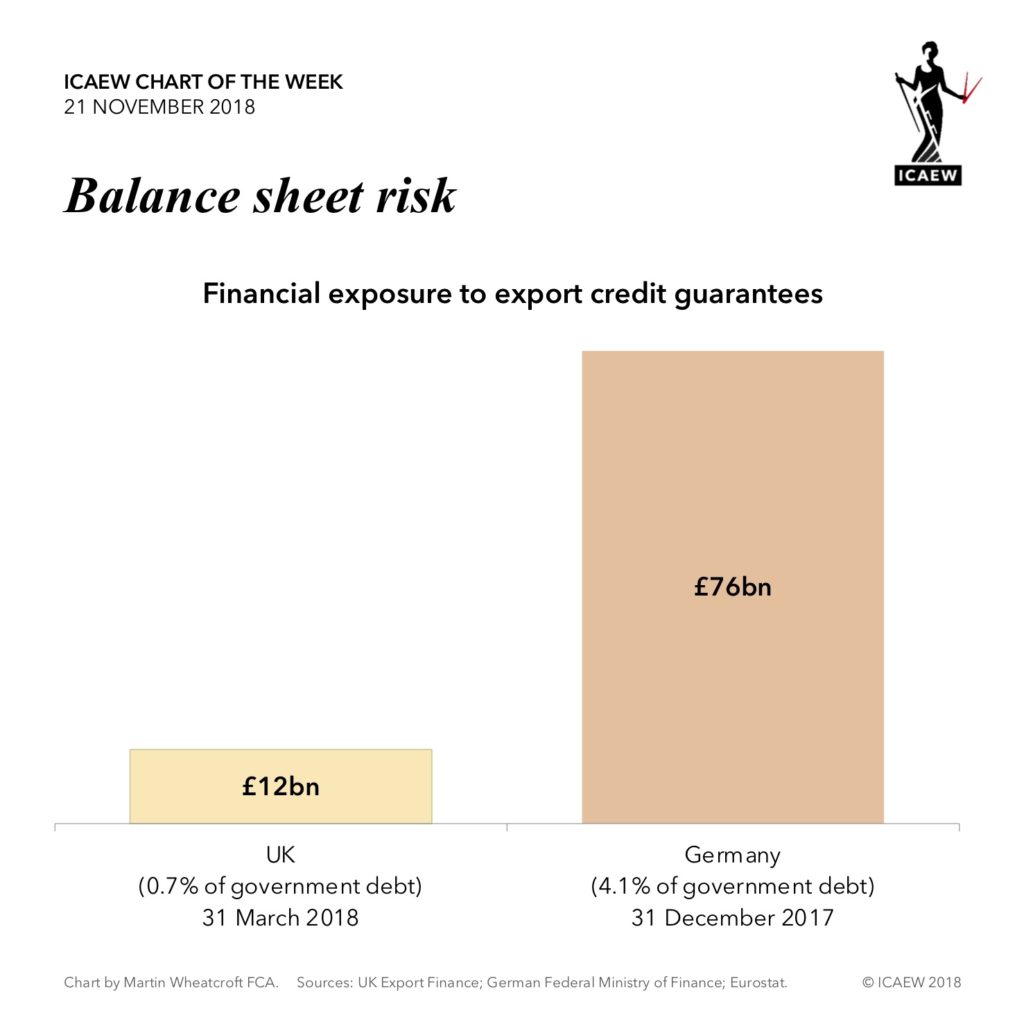

This week’s chart is about export credit guarantees and the associated risk carried on government balance sheet. We compared the exposure of the UK government to guarantees provided by UK Export Finance to the equivalent exposure of the German federal government.

It is important to stress that businesses can and do access other forms of government support such as loans, as well as commercial insurance, letters of credit and other risk management tools. After all, UK exporters do have access to the most sophisticated insurance market in the world.

What this does show is the relative willingness of the UK and German governments to take on risk in order to achieve a policy objective – support to exports. Of course, some of the difference is down to the relative size of the economies. Germany’s economy is over 40% larger than the UK’s.

A fairer comparison for the £12bn UK’s exposure to export credit guarantees might be to an economy-adjusted £53bn rather than the actual £76bn (€86bn) reported by the Federal Ministry of Finance’s export credit guarantee division.

However you measure it, it is clear that the German government has assumed a much higher level of risk to support its exporters that the UK government.

Something to think about.

To join the conversation go to https://ion.icaew.com/talkaccountancy/b/weblog/posts/icaew-chart-of-the-week-71709483.