My chart this week examines the late lamented Silicon Valley Bank and how its outsized investment in securities made it particularly vulnerable to a bank run.

Silicon Valley Bank collapsed on 10 March 2023 after a bank run saw depositors rapidly withdraw funds as they lost confidence in the bank’s ability to survive. The bank’s collapse followed concerns that had been growing since 24 February 2023, when Silicon Valley Bank’s parent company, SVB Financial Group, published its annual consolidated financial statements for the year ended 31 December 2022.

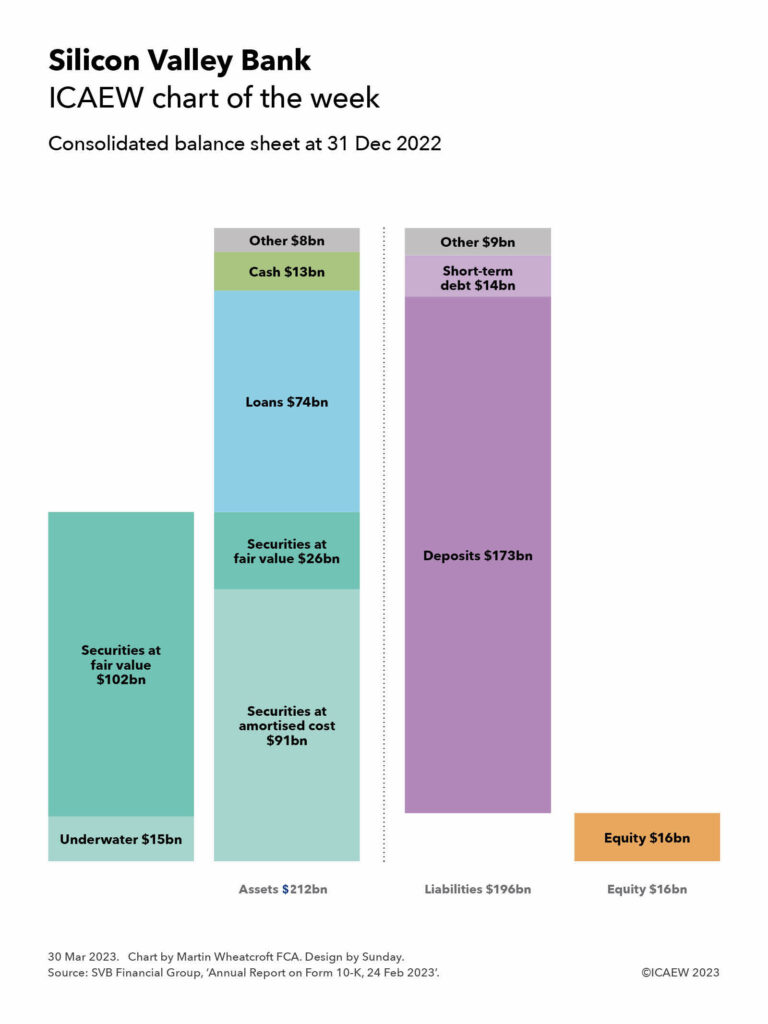

As illustrated by this week’s chart, SVB’s consolidated balance sheet at 31 December 2022 comprised assets of $212bn, liabilities of $196bn and equity of $16bn.

Assets consisted of investment securities recorded at amortised cost of $91bn, investment securities recorded at fair value of $26bn, loans of $74bn, cash of $13m, and other assets of $8bn. Liabilities comprised customer deposits of $173bn, short-term debt of $14bn, and other liabilities of $9bn (including long-term debt of $5bn).

Not shown in the chart is the breakdown of equity of $16bn, which at 31 December 2022 primarily comprised preference stock of $4bn, additional paid-in capital of $5bn and $9bn of retained earnings, less $2bn in negative accumulated other comprehensive income.

As disclosed on the face of the balance sheet, the fair value of SVB’s $91bn portfolio of held-to-maturity investment securities was $15bn below its carrying value at amortised cost, reflecting how the main fixed-asset securities in this category – predominantly federally guaranteed mortgage-backed securities and collateralised-mortgage obligations – had fallen in value as interest rates climbed over the course of 2022. These unrealised losses of $15bn were not that far off the $16bn of equity reported by SVB, suggesting the bank would struggle if it ever had to sell these investments before they matured.

SVB’s intention had been to hold onto these investments, but circumstances changed on 9 March when depositors – concerned about further falls in the value of SVB’s assets as interest rates continued to rise during 2023, and an adverse reaction to a belated capital raising exercise launched by SVB on 8 March – withdrew $42bn in one day. This forced SVB to rapidly liquidate assets and borrow to find the cash required to repay depositors, but by then the first major digital bank run had gained too much momentum, with depositors attempting to withdraw a further $100bn on Friday 10 March. With insufficient cash to repay the amounts requested by SVB’s customers, the bank was closed by regulators that lunchtime.

A similar situation played out in the UK, where £3bn out of £10bn of deposits in SVB’s local subsidiary were withdrawn on Friday 10 March, causing the Bank of England to step in over the weekend to enforce a sale to HSBC for £1, a significant discount to previously reported equity of £1.4bn.

While banking regulators in the US, the UK and elsewhere will pour over the entrails of Silicon Valley Bank (and other recent bank failures such as Signature Bank of New York and Switzerland’s Credit Suisse) for some time to come, most commentators consider SVB to be unusual in how it had (or rather hadn’t) managed its exposure to changes in interest rates. At a minimum, closer regulatory supervision appears a likely consequence.

However, perhaps the biggest legacy of the failure of SVB is the decision of US regulators to protect the full amount of customer deposits and not just those covered by the $250,000 federal deposit insurance cap. For depositors in this mid-size banking institution that is of course good news, but the concern is that this might set a precedent for how to deal with potential bank failures in the future, where the price tag could be very much larger.