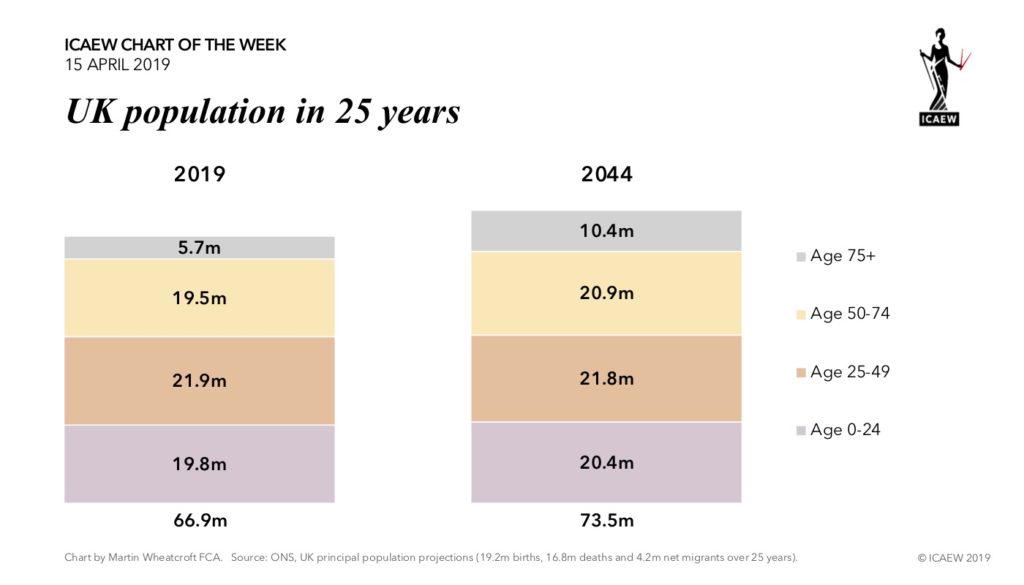

Our #ICAEWchartoftheweek this time is on demographics, illustrating how the population is projected to increase by 10% over the next 25 years, from just short of 67m in June this year to 73½m in 2044.

The ONS have assumed that there will be 770,000 births and 672,000 deaths a year on average over the next quarter of a century, together with annual net inward migration of 168,000. This is an annual increase of 0.4% a year, lower than the 0.6% a year seen over the last twenty-five years, as a consequence of expectations for lower inward migration in the coming years.

What stands out in the chart is the number of people aged 75 or over, which is expected to go up from 5.7m in 2019 to 10.4m in 2044, an increase of 82%!

This is a dramatic change, and is of course good news. But, it will have significant implications for the public finances as increasing sums will be needed to fund state pensions, health, and social care. This will also put pressure on other public services, even if costs can be kept under control on a per person basis.

Unfortunately, there is no money set aside for these costs.

Unlike a number of other countries, social security payments collected from those of working age in the UK are not retained and invested, but are instead disbursed immediately, supporting earlier generations of workers under the ‘pay as you go’ fiscal strategy adopted by successive UK governments. Nor are there any funds available to cover the health or social care costs of those in retirement – when costs are much higher than those of working age.

This means that more and more money will need to be raised in taxes – or – alternatively, state provision for pensions, health and social care for millions of people will need to be dramatically scaled back from that provided today. The latter has already happened to a minor extent with a higher state retirement age, while the state pension triple-lock guarantee of annual increases is looking increasingly vulnerable.

Another option is for higher levels of immigration. This would increase the number of working age people paying into the system, reducing the scale of tax rises and/or cuts in provision that might otherwise be needed. However, this might prove difficult to achieve politically, even if the government wanted to encourage more people to come to the UK.

Unfortunately, there continues to be a lack of a proper debate about the UK’s fiscal strategy. In particular, is it sustainable to continue with the ‘pay as you go’ approach or should we move to a funded approach for some of the state’s financial obligations to its older citizens? While such a change would take time, and so would not be able to relieve some of the immediate pressures on the public finances, building up investment funds over the next quarter of a century might be a way of getting the UK onto a more sustainable path.

In the meantime, I am just keeping my fingers crossed and hoping that ‘my’ free (state-funded) bus pass will still be waiting for me when I eventually retire…