After our summer pause, our ‘chart of the week’ on the public finances is back and celebrating its first anniversary.

We are easing ourselves back in with this one on the interaction of small change and big politics.

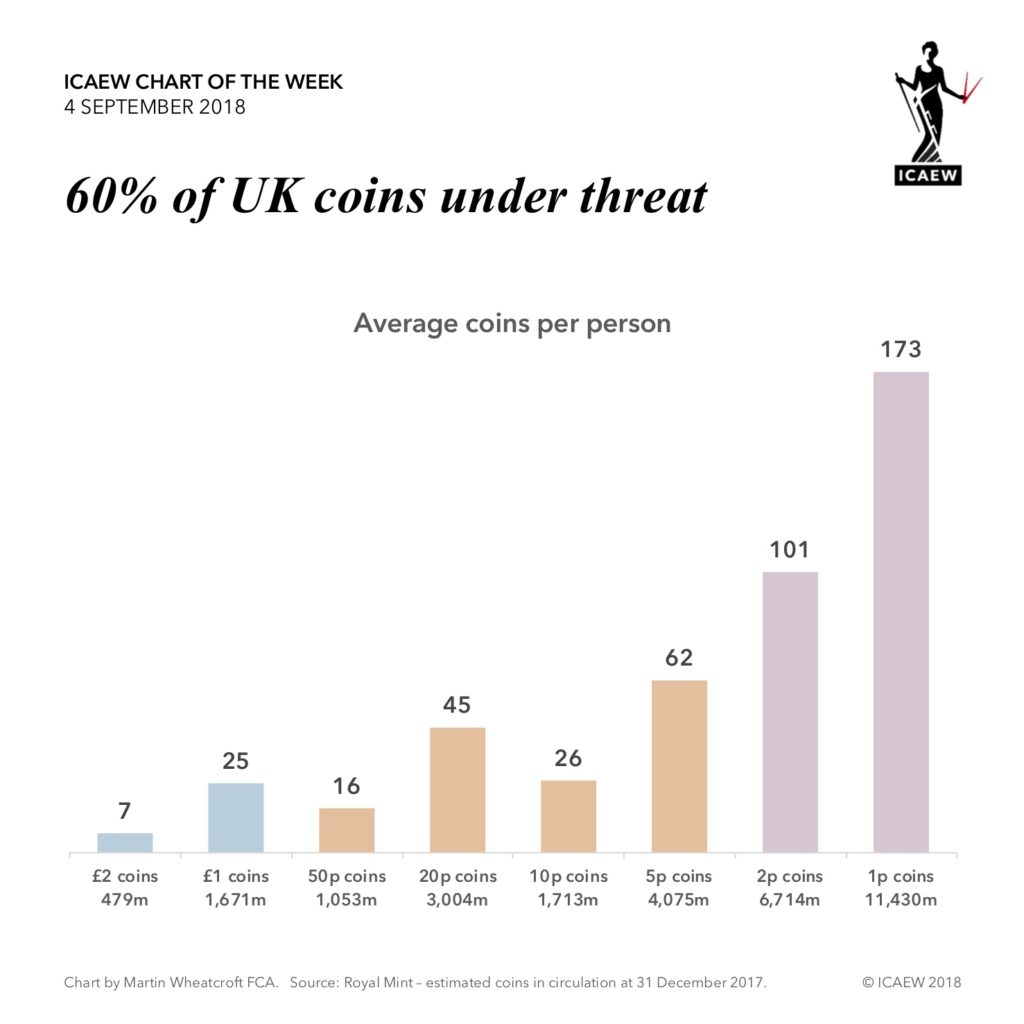

Earlier this year HM Treasury began gathering views on the future of 1p and 2p coins. There are an estimated 11.4bn 1p and 6.7bn 2p coins in circulation making up 60% of the 30.1bn total. They are worth £250m, just over 5% of the £4.6bn total for all coins.

There is a strong economic case for removing them from circulation. A 1p coin costs more to produce that it is worth and a large proportion of 1p and 2p coins are never used again after they are first handed out in change. 2p today is worth the same as one-seventh of a penny when decimal coins were introduced.

Many are to be found in shop tills or in high street banks, but many more are hiding in piggy banks, jam jars or down the backs of sofas. With prices increasingly rounded to nearest 5p, 10p or even £1, and electronic payments on the rise, abolition of 1p and 2p coins is probably only a matter of time.

Nevertheless this is a controversial matter – people are worried about ‘change’ and we don’t have the sense that our political leaders are quite ready to take the plunge.